| Vintage Pulp | Mar 27 2020 |

| Mondo Bizarro | Aug 30 2019 |

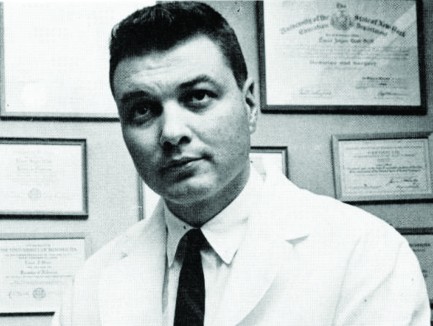

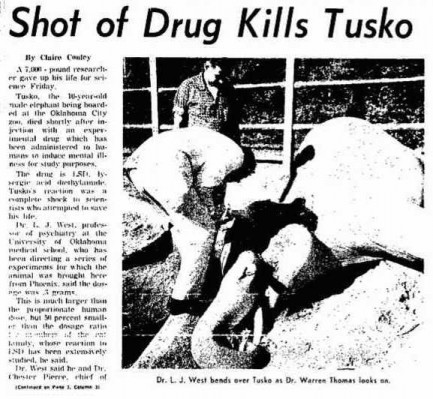

In order to perform the experiment West had to calculate how much acid to give Tusko, and he decisively fucked up. He administered via syringe more than 1,400 times the human dosage (other accounts vary in this regard, but O'Neill relayed the story directly from West's notes). After the injection West stood back to observe the result. Said result, according to West's notes, was “Tusko trumpeted, collapsed, fell heavily onto his right side, defecated,” seized, and died.

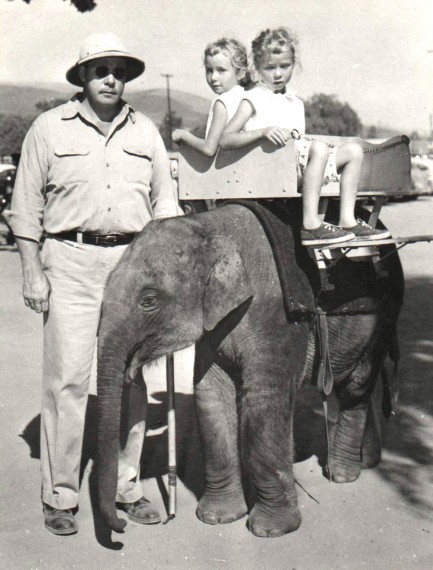

In order to perform the experiment West had to calculate how much acid to give Tusko, and he decisively fucked up. He administered via syringe more than 1,400 times the human dosage (other accounts vary in this regard, but O'Neill relayed the story directly from West's notes). After the injection West stood back to observe the result. Said result, according to West's notes, was “Tusko trumpeted, collapsed, fell heavily onto his right side, defecated,” seized, and died.After the Tusko fiasco West eventually made his way to a research position in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury district, and was there at the same time as Charles Manson, which is why his story appears in O'Neill's book. You'd think he'd been run out out of Oklahoma City on a rail, but you'd be wrong. He had CIA connections, and cruelty is an asset in those quarters. He had already dosed humans without their permission during his days at the CIA's MKUltra program, so it actually represented an improvement in his ethics to do the same to an elephant. They say LSD can bring you into contact with the divine. That must be true, because the story of Louis West and Tusko is a work of divine comedy. And just to give it a tinge of pathos, below is a photo of Tusko on his first birthday, when he had no inkling his life would be cut short in the service of pseudo-science.

| Femmes Fatales | Jul 7 2019 |

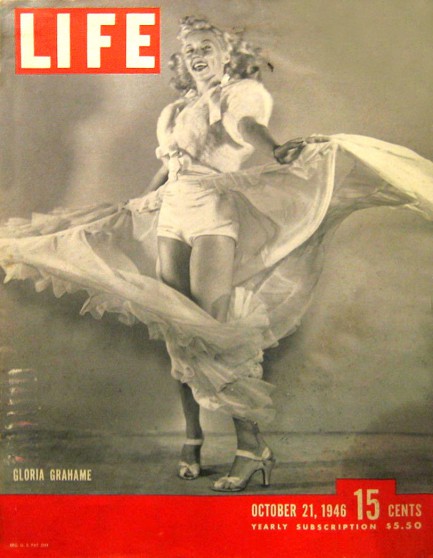

These photos of U.S. actress Gloria Grahame come from one of our favorite old movies, the film noir The Big Heat, in which she starred with Glenn Ford. How many good films was Grahame in? Plenty, including The Bad and the Beautiful, Crossfire, the amazing In a Lonely Place, Human Desire, The Glass Wall, and Odds Against Tomorrow. Outside the drama/noir genres, she was also in It's a Wonderful Life, which is one of the most watched U.S. films of all time, and Oklahoma!. In The Big Heat she plays the prototypical film noir bad girl who wants to be good but has a hard time getting there. We won't say more. Just check it out. The photo is from 1953.

| Vintage Pulp | Jan 12 2017 |

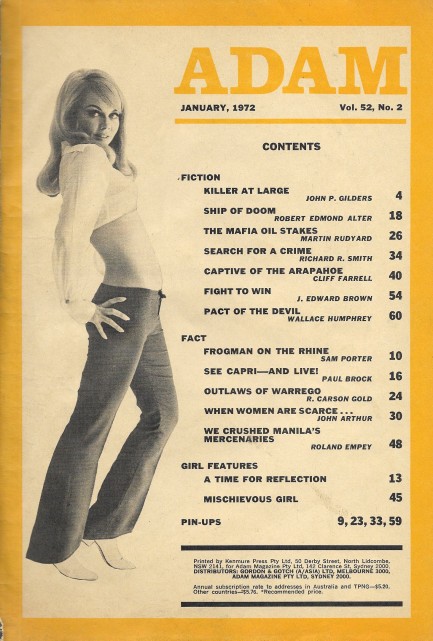

We finally picked up a new scanner and life is good again. You may have noticed the difference in recent uploads. No moire patterns. No weird rainbows. All clean. You may also have noticed the website looks a bit different. We were making some changes over the holidays and got caught in the middle, but we'll finish everything as soon as we can and get it all working properly again. We know, we know. We're really slow with this stuff. But we'll get there.

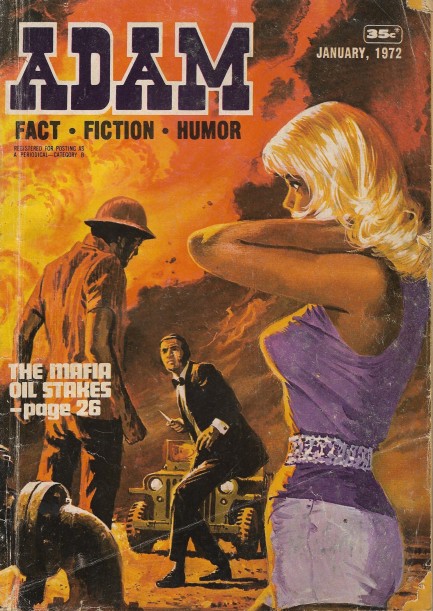

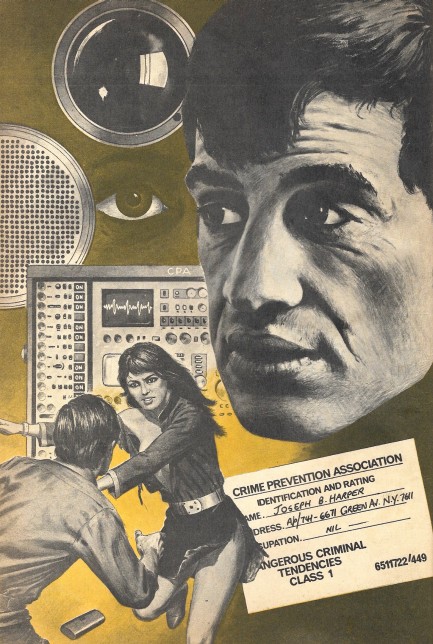

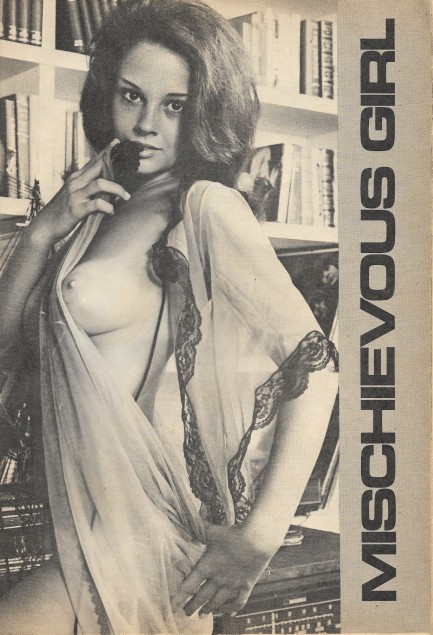

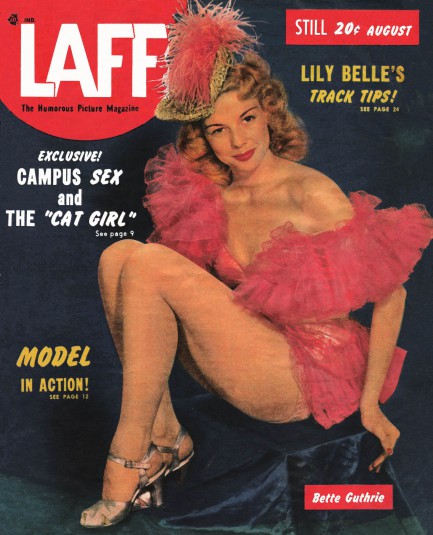

Meanwhile, today we have for your enjoyment an issue of Australia's Adam magazine, published this month in 1972 with a cover illustrating Martin Rudyard's tale “The Mafia Oil Stakes,” about an organized crime cartel trying to take over a group of Oklahoma oil fields. Most of the owners sell out, but one stubborn cuss refuses, and sabotage followed by violence soon results. The climactic fight takes place against the backdrop of an oil well conflagration. A femme fatale is at the root of all this craziness, and her name is Angela Fierce. Sometimes writers try a little too hard, don't they?

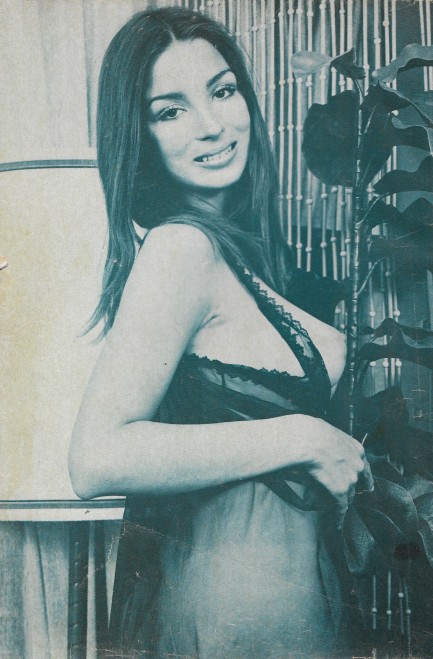

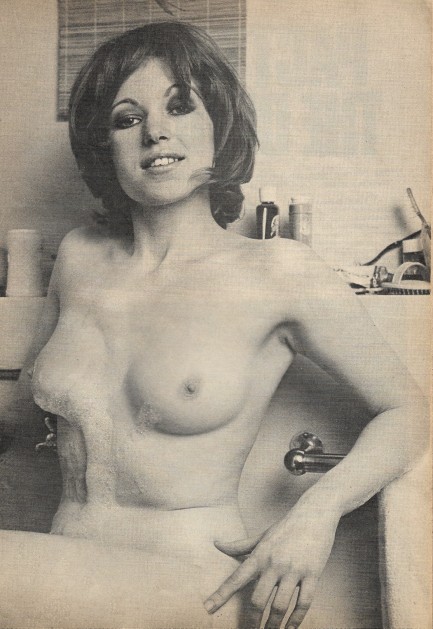

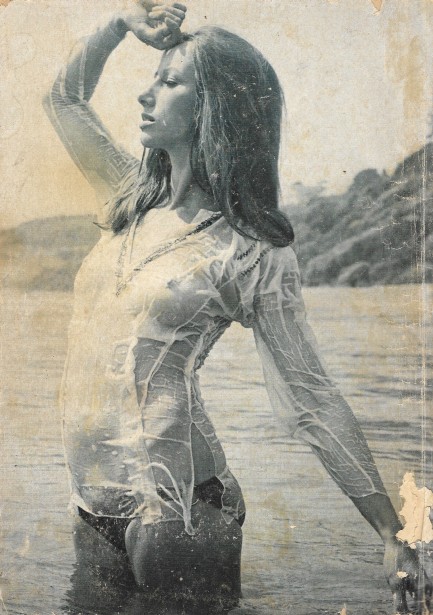

The inside cover star, just above, is Lois Mitchell, someone we've been meaning to feature. She was a popular glamour model during the ’70s, and appeared in copious amounts of high quality images shot by men's magazine contributors Ron Vogel, Edmund Leja, and others. The photo appearing here is new to the internet as far as we can tell. We have thirty-some scans of today's Adam, forty-eight other issues inside the website, and about thirty more we plan on sharing down the line.

| Vintage Pulp | Aug 20 2015 |

| Femmes Fatales | Jan 28 2015 |

| Mondo Bizarro | May 8 2014 |

When you have a site category called mondo bizarro, it’s malpractice to leave stories like this alone. In Oklahoma back in 2012, a state representative named Mike Ritze used a legal loophole to get a plaque of the Ten Commandments installed on the lawn of the statehouse in Oklahoma City. State sponsorship of religious displays is expressly forbidden there because of that whole separation of church and state thing, but because Ritze was also a private citizen and he made a gift of the plaque, it was supposedly not covered by separation laws. An impartial court might have had something different to say about that, but in any case, thanks to Ritze warping state law, Christian groups finally got what they wanted—a religious monument on state property and a brazen in-your-face to America’s founding fathers. Congratulations and backslapping all around.

whether Jewish, Mormon, or other, would be likewise blocked. If they allow the monument, Satanists will have equal standing with God on state property and children who pass by will exclaim, “Mommy, look a goat man! Can I go for a ride?” And if lawmakers remove the Ten Commandments, everyone from Satanists to Constitutional scholars will get what they wanted in 2012, and Ritze and Co. will drink the bitter milk of defeat. Only men blinded by piety could paint themselves into such a corner. For our part, we don’t want Satan at the statehouse, if only to spare Oklahomans the future scandal of certain legislators being caught genuflecting before him under a sickle moon. Do you doubt it? Then you don't know politics.

whether Jewish, Mormon, or other, would be likewise blocked. If they allow the monument, Satanists will have equal standing with God on state property and children who pass by will exclaim, “Mommy, look a goat man! Can I go for a ride?” And if lawmakers remove the Ten Commandments, everyone from Satanists to Constitutional scholars will get what they wanted in 2012, and Ritze and Co. will drink the bitter milk of defeat. Only men blinded by piety could paint themselves into such a corner. For our part, we don’t want Satan at the statehouse, if only to spare Oklahomans the future scandal of certain legislators being caught genuflecting before him under a sickle moon. Do you doubt it? Then you don't know politics.| Vintage Pulp | Jun 5 2013 |

| Hollywoodland | Mar 6 2012 |

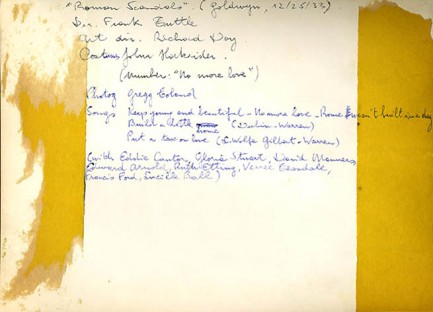

Here’s a rare promo shot from the 1933 pre-Hays Code musical Roman Scandals, an interesting film about a guy from West Rome, Oklahoma who has a vivid dream that he lives in ancient Rome. If you can deal with the sight of Eddie Cantor cavorting in blackface, it’s probably worth a rental. The movie was produced by the Samuel Goldwyn Company, and starred Sam Goldwyn’s dance troupe the Goldwyn Girls, whose most famous ex-member is Lucille Ball. And in fact, that’s Lucille Ball above, on the right, though it may be hard to believe. Trust us, though. The Hays Code, by the way, was actually enacted in 1930 but ignored until 1934, which is why cinema historians consider Roman Scandals to be a pre-Code production. The Code was finally ditched in 1968, but unfortunately in favor of the almost equally arbitrary MPAA rating system. Below, just for the fun of it, we’ve posted the back of the photo because with its writing and tape marks it strikes us as a pretty nice piece of abstract art. And at bottom we’ve posted a much clearer shot of Miss Ball.

| The Naked City | Aug 18 2011 |

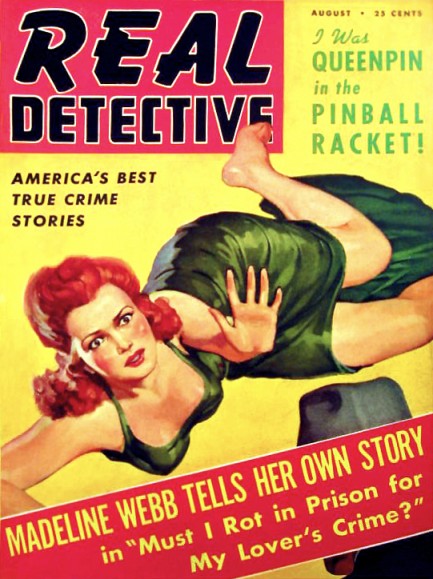

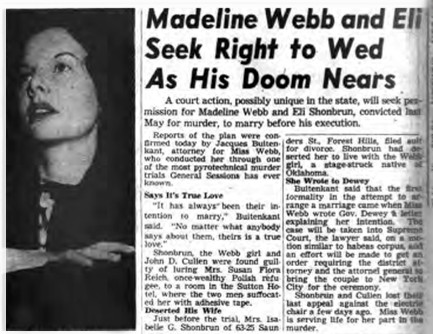

This Real Detective from August 1942 hit newsstands during the height of America’s conflict in the Pacific against the Japanese and it tells the story of Madeline Webb, who was the central figure in a murder case so sensational that it managed to distract the country, however briefly, from war. Webb had moved from Stillwater, Oklahoma to New York City with small town dreams of being a Broadway star. Instead she met a petty crook named Eli Shonbrun and fell in love. Webb was living on an allowance from home, but Shonbrun’s income was more sporadic—he survived by stealing women’s jewelry. Eventually he needed another score and, along with two accomplices named John Cullen and Murray Hirschl, he hatched a scheme to rob a wealthy acquaintance of Webb’s, a woman named Susan Flora Reich.

But when the robbery was over Reich was dead, suffocated by the adhesive tape that had been placed over her mouth. Eli Shonbrun and company went into hiding, but the police soon tracked them down, whereupon Hirschl immediately made a deal to testify against the others. He admitted helping to plan the crime, but swore he was not present in the hotel room where it occurred. Madeline Webb also denied being present, and Shonbrun backed up her claim, but Hirschl said she was lying and had actually lured  Reich to the hotel. A jury of twelve men deliberated for five hours and returned a verdict of guilty for all three defendants. Shonbrun and Cullen were sentenced to death and Webb was given life in prison. When her punishment was announced in court she sobbed, “Please, please, I didn't!” Shonbrun cried, “You have crucifed her!”

Reich to the hotel. A jury of twelve men deliberated for five hours and returned a verdict of guilty for all three defendants. Shonbrun and Cullen were sentenced to death and Webb was given life in prison. When her punishment was announced in court she sobbed, “Please, please, I didn't!” Shonbrun cried, “You have crucifed her!”

What seemed to mesmerize the American public was the spectacle of Webb and Shonbrun clinging to their love in the face of adversity. They had frequently disrupted the trial with outbursts of support for each other. Whenever Webb seemed to wither Shonbrun managed to pass her notes of encouragement. On the few occasions they came into physical contact they kissed and exchanged “I love yous.” And when Shonbrun’s date with the executioner came in April 1943, he received a final love letter from Webb. He read it in the death chamber at Sing Sing Prison, then surrendered it to the warden to be destroyed. Five minutes after being strapped into the electric chair Eli Shonbrun was dead.

Madeline Webb served twenty-five years at Westfield State Farm in Bedford Hills, New York, and was by all accounts a model inmate. She promoted educational programs for imprisoned women, taught many illiterate inmates to read, and ran the prison library. Her life sentence carried no possibility of parole, but her sentence was commuted in 1967. After her release she returned to Stillwater where she worked with various community organizations and cared for her elderly mother, who had spent her life savings on her daughter’s legal fees. Webb died of cancer in 1980 at age sixty-seven, and she did so still protesting her innocence. She was indeed an unlikely murderer. Her family had money back in 1942, and if she had required any she need only have sent a telegram asking for it. But just as New York City proved too much for her show business ambitions, its men may have proved too much for her better judgment. It's entirely possible she was simply too lovestruck by the rough and tumble Eli Shonbrun to derail his scheme. Some light could possibly be shed on this question if the content of her last letter was known—but that went to grave with her.

community organizations and cared for her elderly mother, who had spent her life savings on her daughter’s legal fees. Webb died of cancer in 1980 at age sixty-seven, and she did so still protesting her innocence. She was indeed an unlikely murderer. Her family had money back in 1942, and if she had required any she need only have sent a telegram asking for it. But just as New York City proved too much for her show business ambitions, its men may have proved too much for her better judgment. It's entirely possible she was simply too lovestruck by the rough and tumble Eli Shonbrun to derail his scheme. Some light could possibly be shed on this question if the content of her last letter was known—but that went to grave with her.