| The Naked City | May 25 2022 |

| Femmes Fatales | Mar 26 2015 |

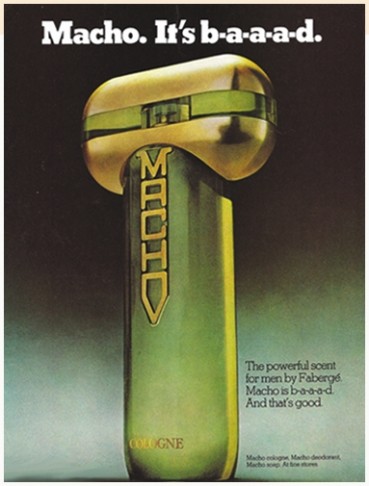

Anne Francis, née Anne Marvak, was born in the prison town of Ossining, New York—location of Sing Sing Correctional Facility. Once she made her escape to Hollywood she became known for her role opposite Leslie Nielsen in the sci-fi film Forbidden Planet, but other notable credits include Bad Day at Black Rock, Rogue Cop, and the television series Honey West, all of which are well worth a gander. This dynamic shot is from the early 1950s.

| Vintage Pulp | Nov 16 2014 |

| The Naked City | Jul 31 2012 |

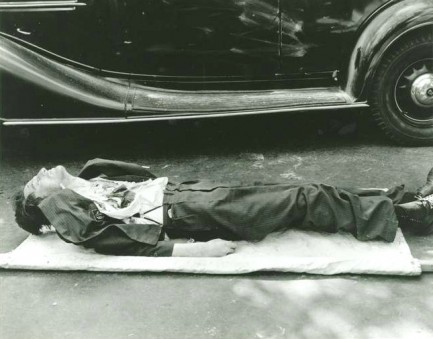

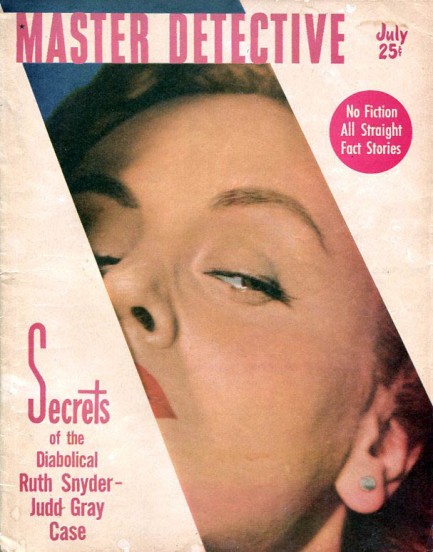

Above, a cover of Master Detective from July 1949, inside of which is a story on Ruth Snyder. In March 1927 Snyder garroted her husband with the help of her lover, a corset salesman named Henry Judd Gray. The couple had been after insurance money, but instead they were caught, tried, and sentenced to death by means of electrocution. On the day of the event, which took place at Sing Sing Prison, a photographer named Tom Howard entered the execution chamber as a witness. He was under assignment for the New York Daily News, but was actually based in Chicago, which meant he was unknown to prison authorities in the New York area. That was important, because Howard’s assignment was to illegally take a photo of Ruth Snyder’s execution, which had considerable tabloid value because she would be the first woman put to death at Sing Sing since 1899. Howard was ingeniously prepared—he had strapped a camera to his ankle, and had fed a shutter release up one pant leg to an accessible point inside his suit jacket. At the moment the executioner threw the switch, Howard lifted his pant leg and snapped the blurry photo below, which appeared the next day in the New York Daily News under a huge header that read simply: Dead! The issue was a sensation, the image became iconic, and Howard became nationally famous.

| The Naked City | Aug 18 2011 |

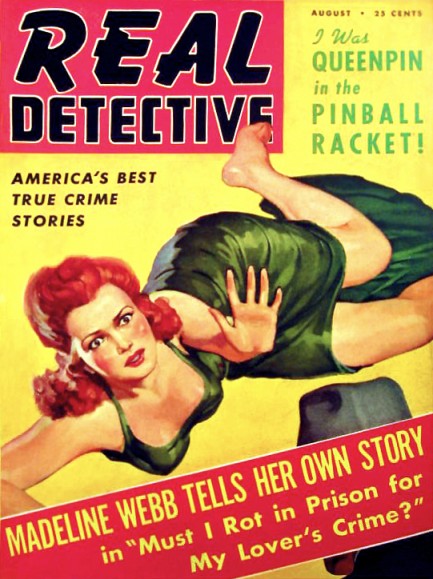

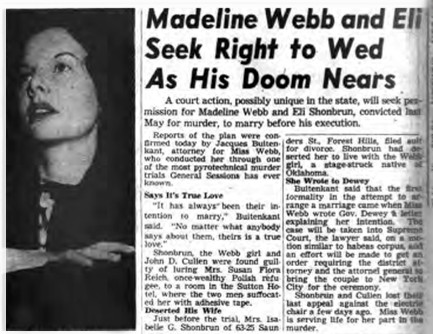

This Real Detective from August 1942 hit newsstands during the height of America’s conflict in the Pacific against the Japanese and it tells the story of Madeline Webb, who was the central figure in a murder case so sensational that it managed to distract the country, however briefly, from war. Webb had moved from Stillwater, Oklahoma to New York City with small town dreams of being a Broadway star. Instead she met a petty crook named Eli Shonbrun and fell in love. Webb was living on an allowance from home, but Shonbrun’s income was more sporadic—he survived by stealing women’s jewelry. Eventually he needed another score and, along with two accomplices named John Cullen and Murray Hirschl, he hatched a scheme to rob a wealthy acquaintance of Webb’s, a woman named Susan Flora Reich.

But when the robbery was over Reich was dead, suffocated by the adhesive tape that had been placed over her mouth. Eli Shonbrun and company went into hiding, but the police soon tracked them down, whereupon Hirschl immediately made a deal to testify against the others. He admitted helping to plan the crime, but swore he was not present in the hotel room where it occurred. Madeline Webb also denied being present, and Shonbrun backed up her claim, but Hirschl said she was lying and had actually lured  Reich to the hotel. A jury of twelve men deliberated for five hours and returned a verdict of guilty for all three defendants. Shonbrun and Cullen were sentenced to death and Webb was given life in prison. When her punishment was announced in court she sobbed, “Please, please, I didn't!” Shonbrun cried, “You have crucifed her!”

Reich to the hotel. A jury of twelve men deliberated for five hours and returned a verdict of guilty for all three defendants. Shonbrun and Cullen were sentenced to death and Webb was given life in prison. When her punishment was announced in court she sobbed, “Please, please, I didn't!” Shonbrun cried, “You have crucifed her!”

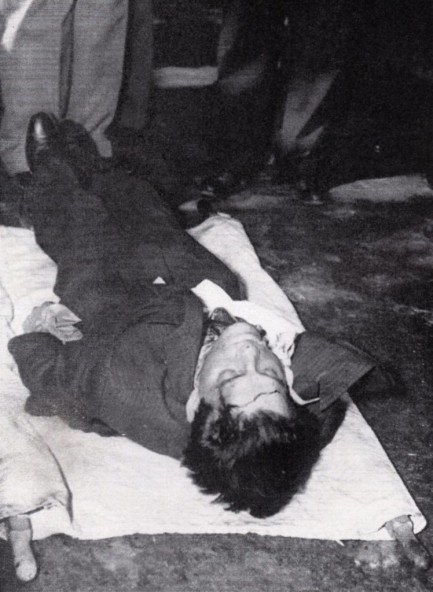

What seemed to mesmerize the American public was the spectacle of Webb and Shonbrun clinging to their love in the face of adversity. They had frequently disrupted the trial with outbursts of support for each other. Whenever Webb seemed to wither Shonbrun managed to pass her notes of encouragement. On the few occasions they came into physical contact they kissed and exchanged “I love yous.” And when Shonbrun’s date with the executioner came in April 1943, he received a final love letter from Webb. He read it in the death chamber at Sing Sing Prison, then surrendered it to the warden to be destroyed. Five minutes after being strapped into the electric chair Eli Shonbrun was dead.

Madeline Webb served twenty-five years at Westfield State Farm in Bedford Hills, New York, and was by all accounts a model inmate. She promoted educational programs for imprisoned women, taught many illiterate inmates to read, and ran the prison library. Her life sentence carried no possibility of parole, but her sentence was commuted in 1967. After her release she returned to Stillwater where she worked with various community organizations and cared for her elderly mother, who had spent her life savings on her daughter’s legal fees. Webb died of cancer in 1980 at age sixty-seven, and she did so still protesting her innocence. She was indeed an unlikely murderer. Her family had money back in 1942, and if she had required any she need only have sent a telegram asking for it. But just as New York City proved too much for her show business ambitions, its men may have proved too much for her better judgment. It's entirely possible she was simply too lovestruck by the rough and tumble Eli Shonbrun to derail his scheme. Some light could possibly be shed on this question if the content of her last letter was known—but that went to grave with her.

community organizations and cared for her elderly mother, who had spent her life savings on her daughter’s legal fees. Webb died of cancer in 1980 at age sixty-seven, and she did so still protesting her innocence. She was indeed an unlikely murderer. Her family had money back in 1942, and if she had required any she need only have sent a telegram asking for it. But just as New York City proved too much for her show business ambitions, its men may have proved too much for her better judgment. It's entirely possible she was simply too lovestruck by the rough and tumble Eli Shonbrun to derail his scheme. Some light could possibly be shed on this question if the content of her last letter was known—but that went to grave with her.

| Intl. Notebook | Jun 1 2011 |

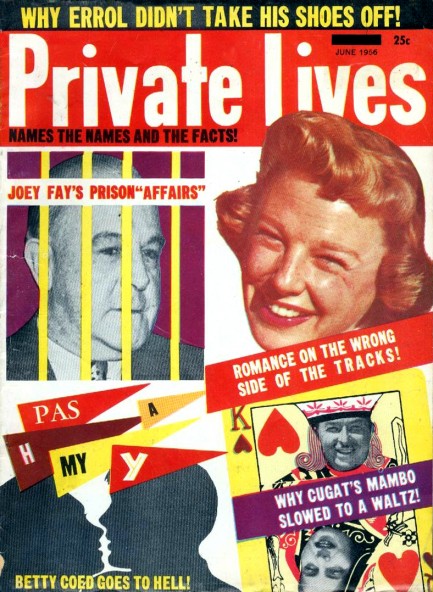

This issue of Private Lives from June 1956 with its cover story about Joey Fay teaches us the basic facts of plausible deniability as it works in the political arena. Fay was vice president of the A.F.L. International Union of Operating Engineers based in New York, and in 1945 he was hit with an eighteen-year sentence to Sing Sing Prison for extortion. Within months rumors sprang up that even though he was behind bars he was still running rackets in New York City. A second scandal involving Fay's involvement in crooked horse racing finally prompted some clever reporter, curious who was relaying directives between Sing Sing and NYC, to come up with the genius idea of requesting a list of his visitors. That list turned out to be pure dynamite—it was a roster of practically every prominent east coast politician and official within a two-hundred mile radius. We’re talking the majority leader in the state senate, acting lieutenant governor George Wicks, a former state supreme court justice, state senator William Condon, the mayor of Jersey City, the former mayor of Newark, and on and on. Eighty-seven callers in total, whose visits comprise the “affairs” Private Lives speaks of on its cover.

The embarrassing revelation produced three results. First, the politicians and officials who had visited Fay were forced to concoct highly improbable excuses that the public nevertheless had to accept because nobody knew the exact content of their conversations. Wicks explained his visit this way: “I never consulted or talked with Joseph Fay about anything else but labor conditions in the counties I represent.” See how that plausible deniability stuff works? The second result of the scandal was that Fay was transferred 250 miles upstate to Clinton Prison in Dannemora, NY, where conditions were not nearly as nice as at Sing Sing and he was considerably harder to visit. And third, public officials nationwide stopped visiting criminals in prison. Go and figure. And if there was a fourth result, possibly it was this: a generation of New York voters learned what every generation of voters always re-learns—politicians are exactly as corrupt as lack of scrutiny allows them to be.

| The Naked City | Nov 23 2010 |

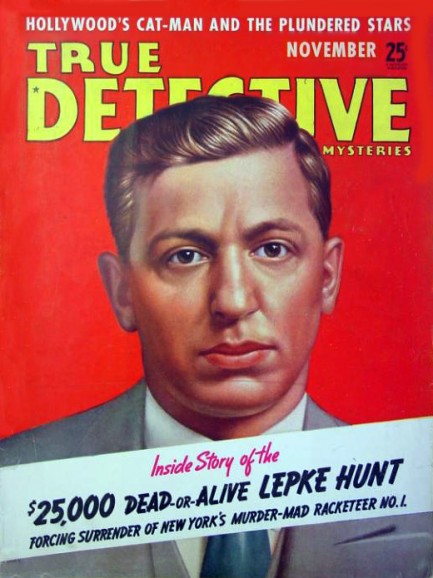

This True Detective from November 1939 features a cover painting of mobster Louis “Lepke” Buchalter, whose flight from authorities had taken him from the U.S. to Mexico, and then to Costa Rica, Puerto Rico and Cuba, and across the ocean to England, France and Germany. Buchalter had begun his career in organized crime by shaking down pushcart operators in Brooklyn, and had risen through the ranks of the criminal-controlled fur industry by doing every type of dirt imaginable, from issuing threatening phone calls to garment union activists to throwing acid in a competitor’s face. Eventually he was running a criminal empire that stretched to both coasts, and was acting as head of the infamous assassination squad Murder, Inc.

In 1936 Buchalter went into hiding after he became aware that criminal charges were being prepared against him. Not long after he dropped out of sight, he was indicted for smuggling an estimated $10 million in heroin into the U.S. from Hong Kong. The FBI printed a million posters and displayed them in every post office, police station, and federal building in America. All this attention was a problem for U.S. mob bosses, and so with characteristic unsentimentality, they decided Buchalter had to surrender. Convincing him was not difficult. While he undoubtedly had the flair and intelligence to dodge the feds indefinitely, living in another country away from the old neighborhood and away from the hundreds of underlings who respected him was not his style. Buchalter was a mobster through-and-through. To him, an anonymous existence, even in a tropical paradise or cosmopolitan foreign capitol, was little different from being in prison.

Buchalter’s associates got word to him that if he came back to the U.S. he would be able to surrender personally to J. Edgar Hoover. Surrendering to the Feds meant he would not face a more serious group of charges brought by Manhattan D.A. Thomas Dewey. But it was wishful thinking. The federal charges were rapidly followed by Dewey’s charges and Buchalter earned a fourteen-year jolt in the pen. His legal team hoped to have the sentence reduced via appeals and procedural maneuvers, but when a snitch fingered Buchalter for ordering the murder of a candy store owner named Joe Rosen, he was tried for the killing, convicted, and sentenced to execution. By some estimates Buchalter had been responsible for a thousand murders as head of Murder, Inc., but all it took was one to seal his fate. Louis "Lepke" Buchalter was electrocuted in Sing Sing prison's famous "Old Sparky" electric chair on March 4, 1944, perhaps while realizing life on a beach in Costa Rica hadn’t been so bad after all.

have the sentence reduced via appeals and procedural maneuvers, but when a snitch fingered Buchalter for ordering the murder of a candy store owner named Joe Rosen, he was tried for the killing, convicted, and sentenced to execution. By some estimates Buchalter had been responsible for a thousand murders as head of Murder, Inc., but all it took was one to seal his fate. Louis "Lepke" Buchalter was electrocuted in Sing Sing prison's famous "Old Sparky" electric chair on March 4, 1944, perhaps while realizing life on a beach in Costa Rica hadn’t been so bad after all.