She's cold blooded. That's why she wears fur even indoors.

Here's a menacing promo image of Joan Crawford made when she was filming her 1949 melodrama Flamingo Road. This is a crop of a larger photo in which she's taking aim at villain Sydney Greenstreet, who made the mistake of getting on her bad side. We talked about the movie recently. Shorter version: Crawford absolutely killed.

Joan is in her sweet spot with a challenging film role.

How do you judge a great acting performance? One way is when beforehand you look at the performer and the part and say, “Impossible, doesn't fit, can't possibly work,” then it does. Flamingo Road, which premiered in the U.S today in 1949, features Joan Crawford as a carny performer and it doesn't fit. But probably nobody would seem to fit. The main character evolves over years from carny chippie into upper crust lady, so either way a filmmaker would have to make a difficult choice—cast an ingenue who evolves into a sophisticated middle-aged woman, or cast a mature actress and hope she can play young. They chose the later option with Crawford, and it can't possibly work. But this is Crawford we're talking about—she could make most any role work, and does so here with a typically assured performance.

Flamingo Road is set in the American south and is about the social mores and political machinations of a small but wealthy town. The title refers to the enclave where the rich and powerful live together in their mansions and manors. The carny version of Crawford falls for local deputy sherrif Zachary Scott, but he's been tabbed by local kingpin Sydney Greenstreet to be his puppet in the state senate. As part of that plan Scott is to marry into wealth. Cavorting with a carny isn't going to fly. Greenstreet decides to break them up, or hurt Crawford trying, and there's nothing so underhanded or injurious that he won't do it. Crawford, though, is tougher than anyone expects, and what she learns from her travails is, first: she's going to make it to Flamingo Road no matter what it takes; and second: she will have her revenge. That's all we'll tell you about the plot.

Flamingo Road is another of those movies that's often called a film noir, and while we don't try to be gatekeepers of what is and isn't noir—because we have no authority to do so—we also don't avoid stating the obvious. Flamingo Road isn't a film noir. Some entities, including respected ones, have a vested interest in casting the noir net as widely as possible. If you host noir festivals, for example, after a while you need to expand your defintion of noir to keep your slate fresh. If you write film noir books, you might want to demonstrate that you think outside the box by including Chinatown or Lat sau san taam or The Limey (all excellent movies, by the way).

At the opposite extreme, several prominent critics attest that film noir doesn't exist at all. That's like saying there's no such thing as superhero movies because costumed heroes are just further iterations of superpowered characters such as Rambo. Superhero movies exist. So does film noir, though it resides within the wider genres of crime and drama. However, it's too easy to call any movie with conflict and a few neon-splashed night sequences a noir. Film noir is as much thematic as it is iconographic. In every way that we can discern, Flamingo Road isn't one. The definitive American Film Institute calls it a melodrama. We agree. It's a melodrama in which a good actress, aged north of forty, overcomes difficult casting to knock her years-spanning role out of the park.

Crawford tries to get away from it all, only to have it all come to her.

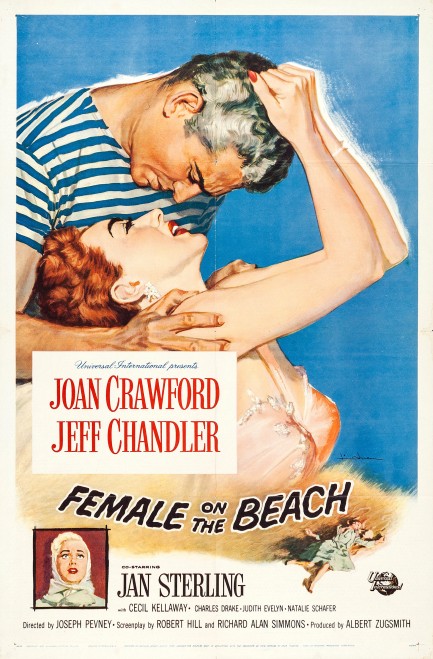

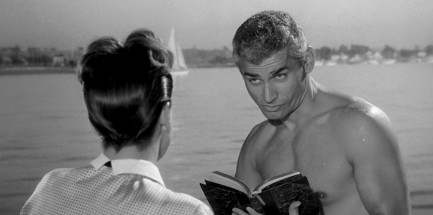

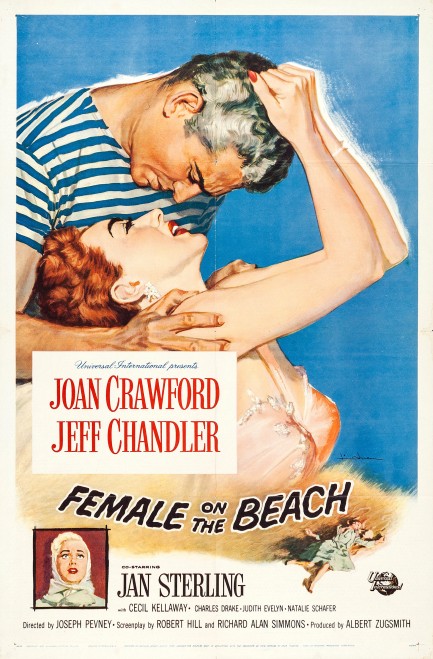

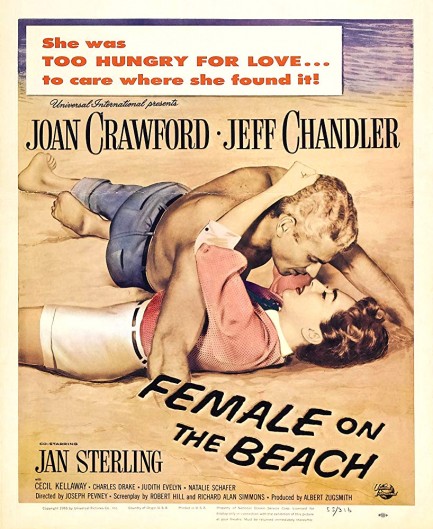

We've been neglectful of Joan Crawford, but we remedied that at least partly last night by screening her drama Female on the Beach, which premiered today in 1955. Plotwise this is pretty straightforward. Seeking peace and quiet, Crawford moves into a Newport Beach seaside house owned by her late husband. It's usually rented, but the previous tenant has just vacated the place. Crawford soon learns that the tenant vacated alright—by way of a swan dive off the deck onto the beach. But whether this was an accident, suicide, or the wicked work of someone's hand is unclear. What viewers do learn is that the neighbors—played by Cecil Kellaway and Natalie Schafer, aka Lovie Howell from Gilligan's Island—are con artists. They partner with a local boytoy played by hunky Jeff Chandler, helping him to romance vacationing women and divide them from their cash. This may be why the previous occupant of Crawford's house ended up dead.

The plot set-up is interesting enough, but the most notable aspect of Female on the Beach is that it's another one of those old movies that shows how little ownership mid-century women had over their bodies and spaces. Chandler is a lothario, which of course means he's scripted as romantically insistent, but even factoring that into his character his sheer presumption is amazing. As a viewer you absorb it on two levels: cinematically and sociologically. Chandler's behavior, though fictional, is rooted in 1950s reality. The filmmakers wanted him to be forward but a little charming, and that fact will instill within you a sense of wonder and amazement at what women were expected to endure. Chandler paws and manhandles Crawford against her will, and when she objects he treats her as though something is wrong with her. He refuses to remove his boat from her pier, enters her house without permission and refuses leave when asked, answers a knock at her door though told not to do so, initially avoids returning a key he acquired before she moved in, feels her leg without consent, embraces her against her will, and more. “A woman's no good to a man unless she's a little afraid of him,” Chandler tells her at one point. Big red flag.

At first Crawford hates the guy, but eventually he sucks her in by pouting, being surly, pretending a loss of interest. We'd say nobody would fall for it, but we've seen it work. When Crawford finds a diary hidden by the dead woman she learns about Chandler's scams, but even this won't scare her off. She just can't resist the big lug. Is he a killer? Is she a moron? Do viewers need so many hints that the railing of her beach house is ready to give way? All of these are pertinent questions, but in terms of enjoying Female on the Beach what's most important is whether you can accept Crawford's attraction to Chandler's retrograde alpha male. If so, then lay on. But even if watching their antics sets your teeth on edge, the movie is probably worth a viewing just to see an evil Mrs. Howell. If all else fails, perhaps you'll want to watch it to observe Joan Crawford at work. She was one of Hollywood's great stars—even in not-great movies. That's Female on the Beach—not great, but not bad.

Hi, take a real good look at me, baby, because I'll be your stalker. Hi, take a real good look at me, baby, because I'll be your stalker.  See? Stalking. Here I am in your kitchen this morning without permission. See? Stalking. Here I am in your kitchen this morning without permission.

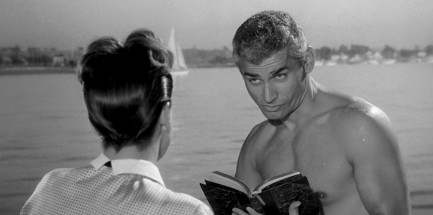

Surprise! Stalking! This time I swam all the way across the bay to stalk you. Surprise! Stalking! This time I swam all the way across the bay to stalk you.

Lovely calves. Shapely but not too developed. Which means you won't be able to outrun me. Lovely calves. Shapely but not too developed. Which means you won't be able to outrun me.

Is this your diary? I'm gonna read it. I know—presumptuous as hell, right? Is this your diary? I'm gonna read it. I know—presumptuous as hell, right?

Wow. You write that I'm a walking vomit stain with sadistic eyes, the manners of a crocodile, and a bulge in my swimsuit the size of a wine cork. Wow. You write that I'm a walking vomit stain with sadistic eyes, the manners of a crocodile, and a bulge in my swimsuit the size of a wine cork.

You've been looking at my bulge, eh? You've been looking at my bulge, eh?

I hate you, lady. That's reverse psychology. It's right out of the stalker's handbook. I hate you, lady. That's reverse psychology. It's right out of the stalker's handbook.

Not so fast, Joan. What do you take me for? Let the delicious irony stretch out a little. In fact, maybe I won't even kiss you. That'd teach you. Not so fast, Joan. What do you take me for? Let the delicious irony stretch out a little. In fact, maybe I won't even kiss you. That'd teach you.

Just kidding. Let's do this. Tonsils here I come. Just kidding. Let's do this. Tonsils here I come.

There's something about that man... There's something about that man...

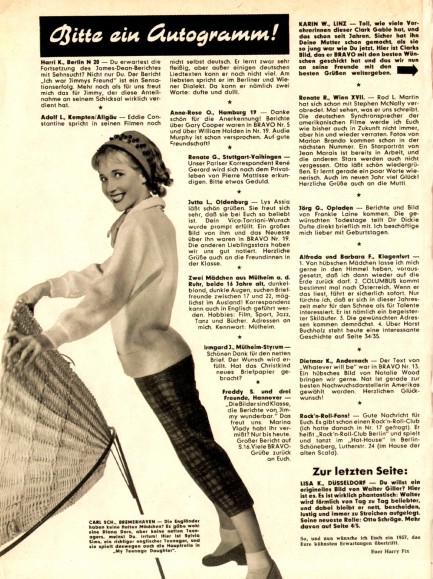

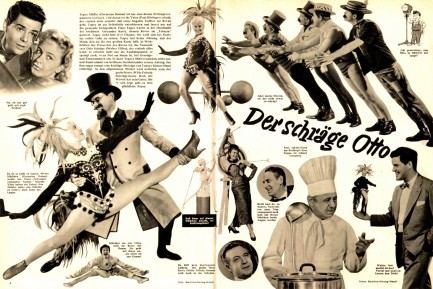

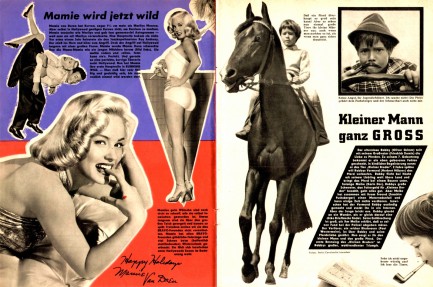

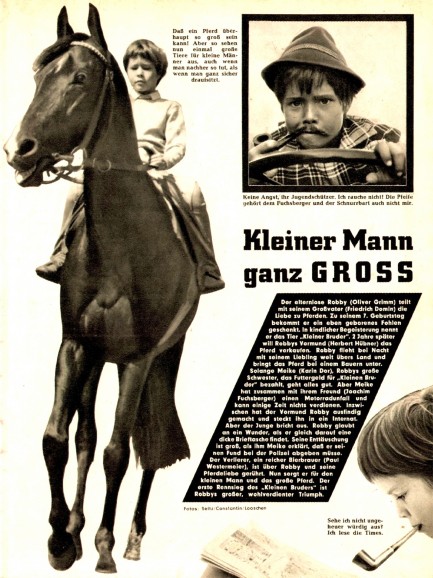

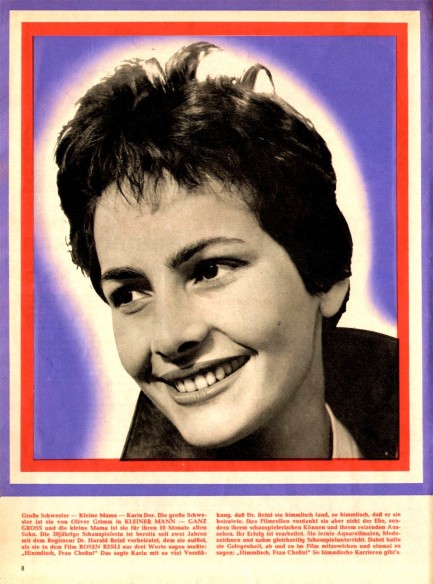

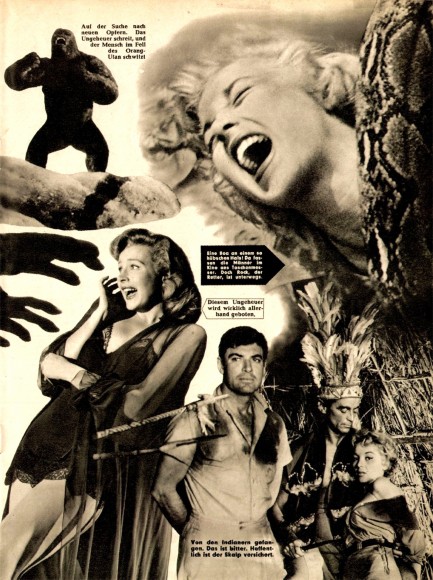

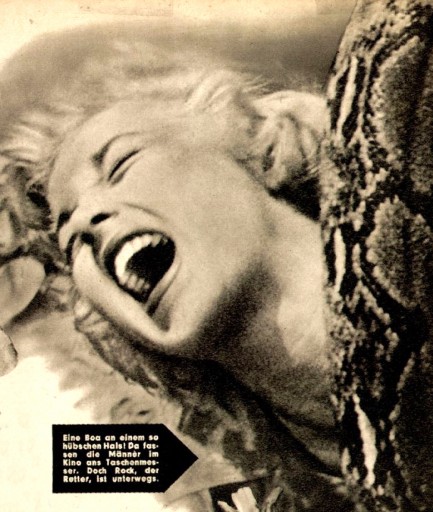

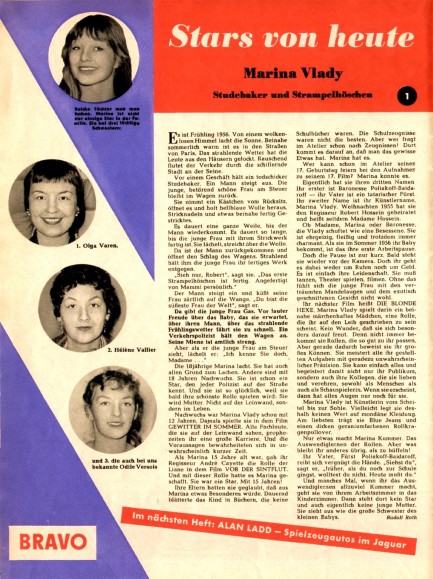

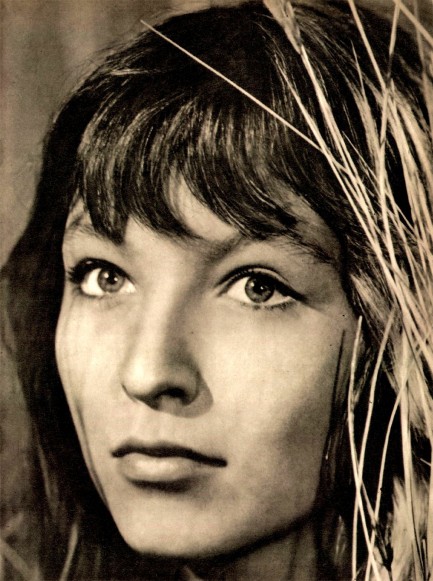

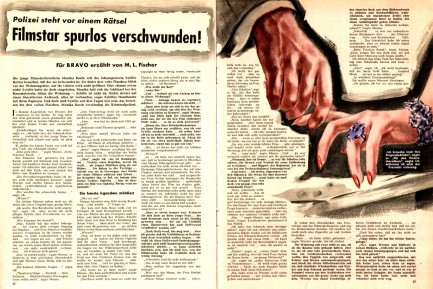

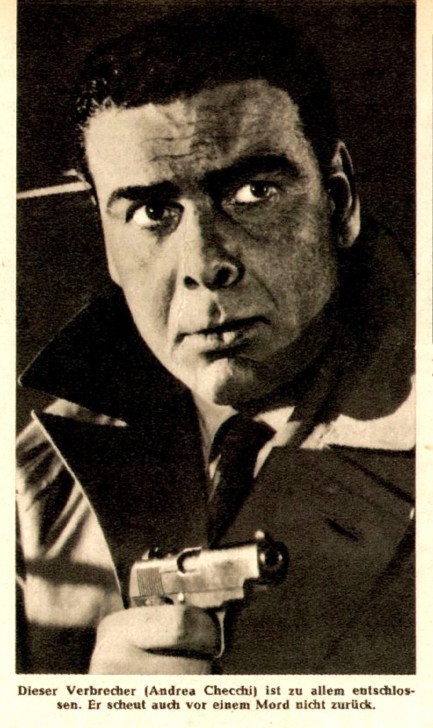

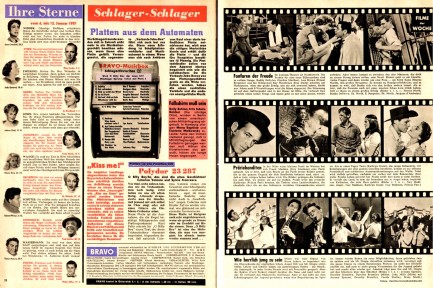

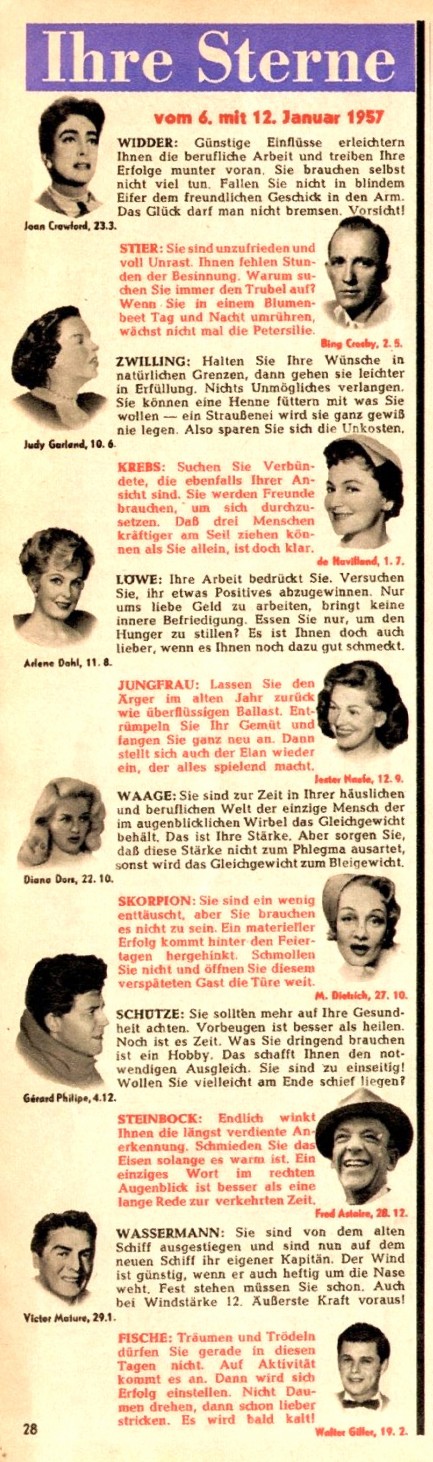

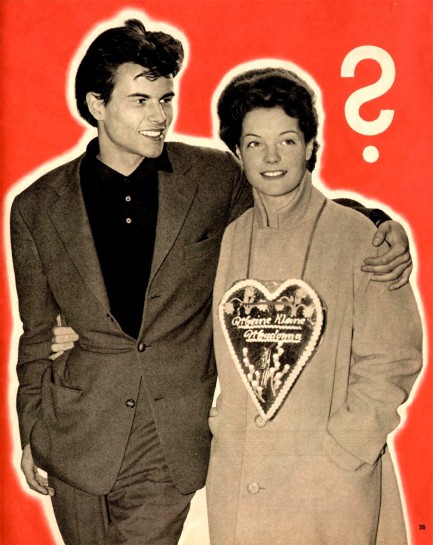

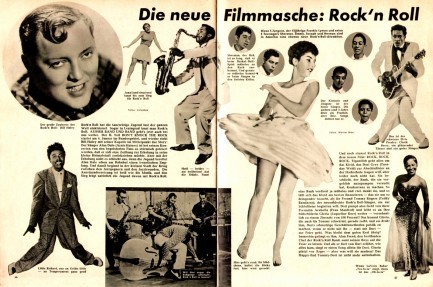

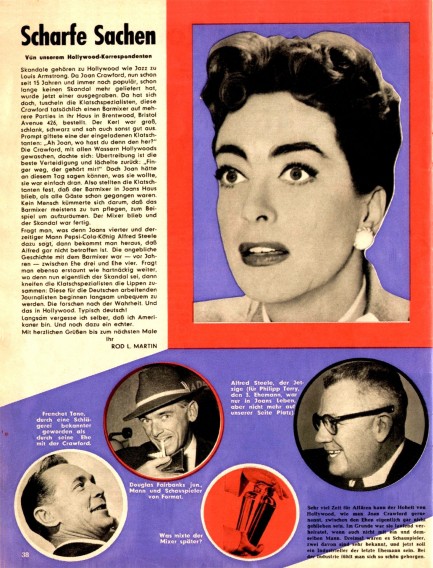

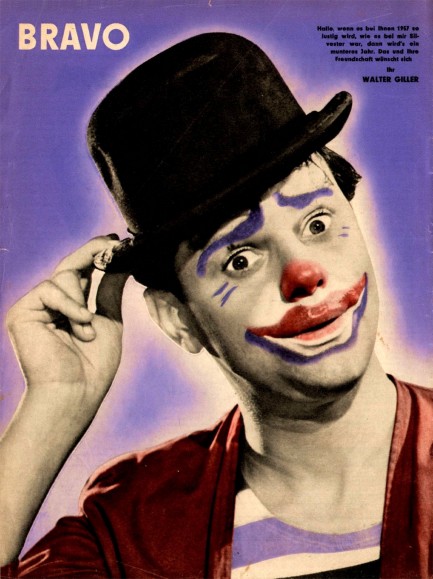

West German magazine tears down the wall.

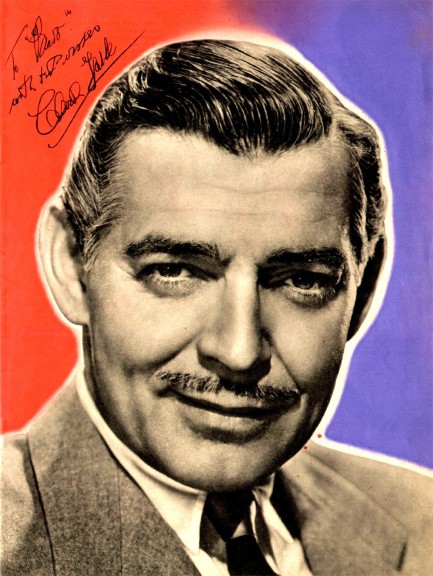

German isn't one of our languages, but who needs to read it when you have a magazine with a red and purple motif that's pure eye candy? Every page of this issue of the pop culture magazine Bravo says yum. It hit newsstands today in 1957 and is filled with interesting and rare starfotos of celebs like Romy Schneider, Horst Buchholz, Clark Gable, Karin Dor, Mamie Van Doren, Ursula Andress, Marina Vlady, Corinne Calvet, jazzists Oscar Peterson and Duke Ellington, and many others. This was an excellent find.

We perused other issues of Bravo and it seemed to us—more so in those examples than this one—that it was a gay interest publication. After a scan around some German sites for confirmation we found that it was as we thought. The magazine's gay themes were subtle, but they were there, and at one blog the writer said that surviving as a gay youth in West Berlin during the 1960s, for him, would have been impossible without Bravo. We will have more from this barrier smashing publication later. Thirty-five panels below.

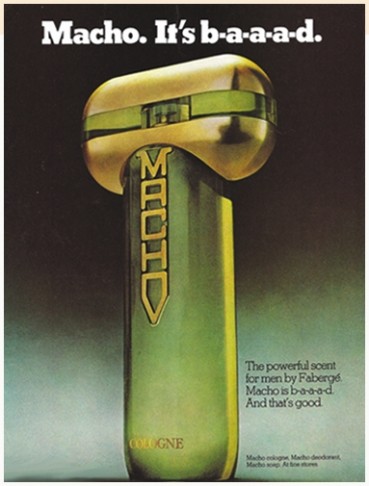

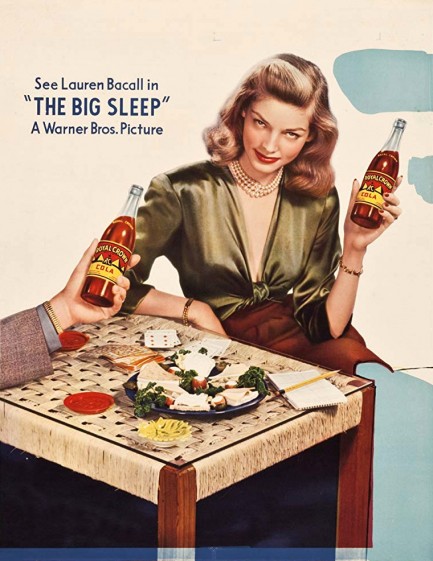

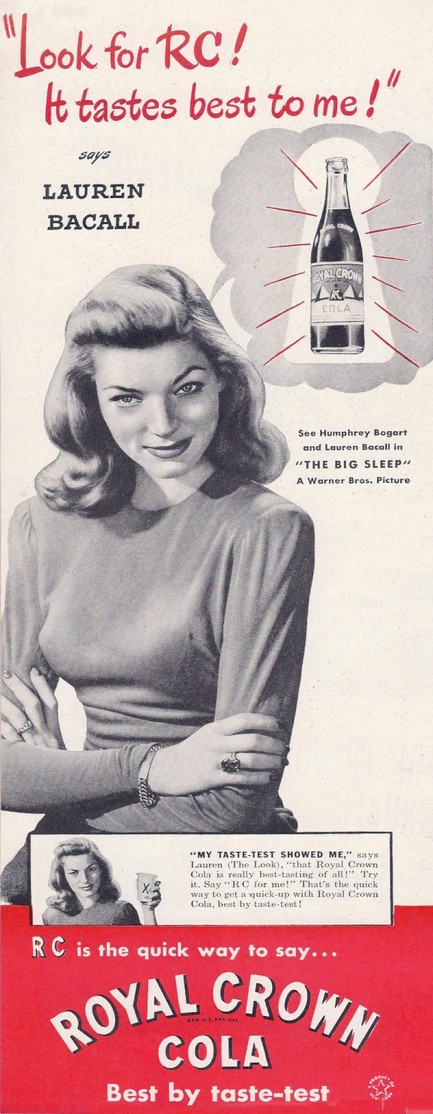

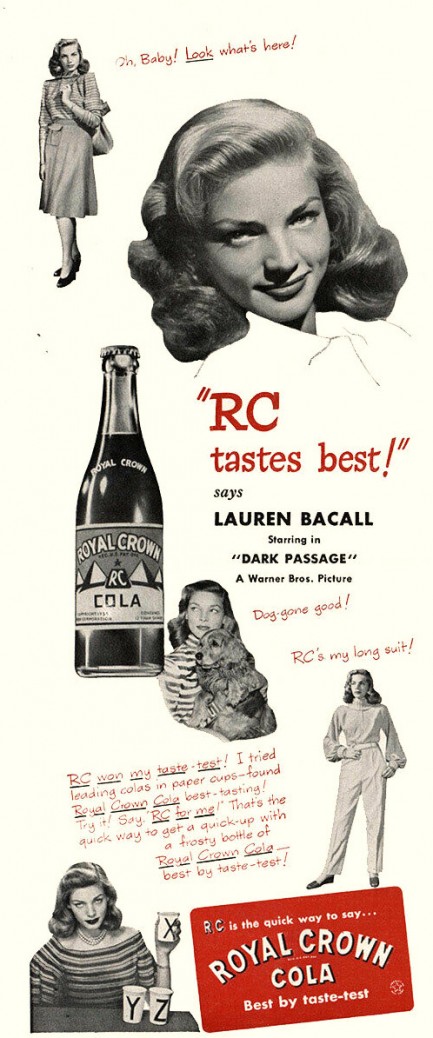

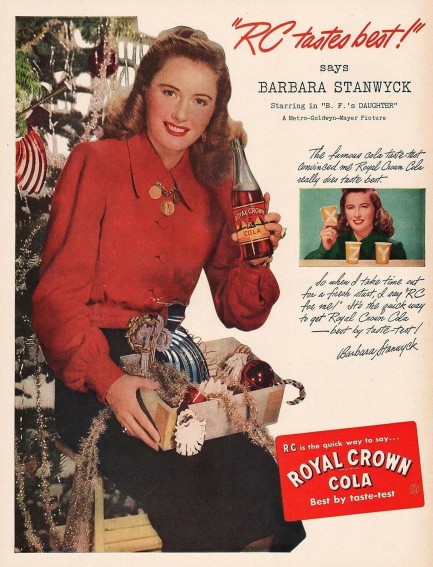

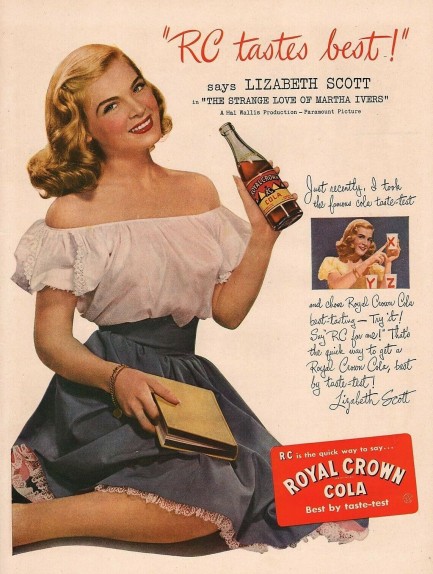

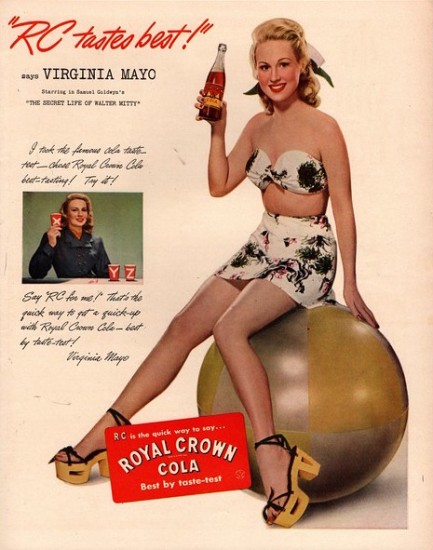

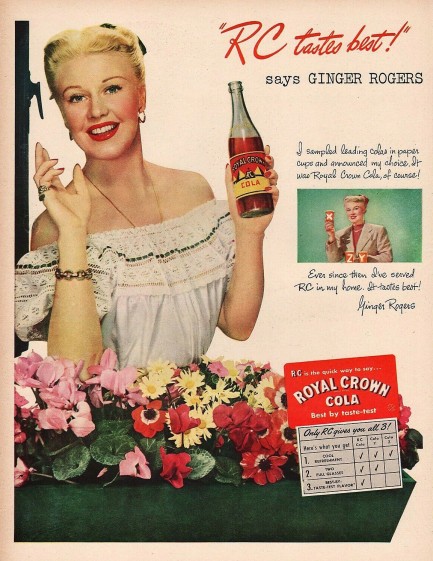

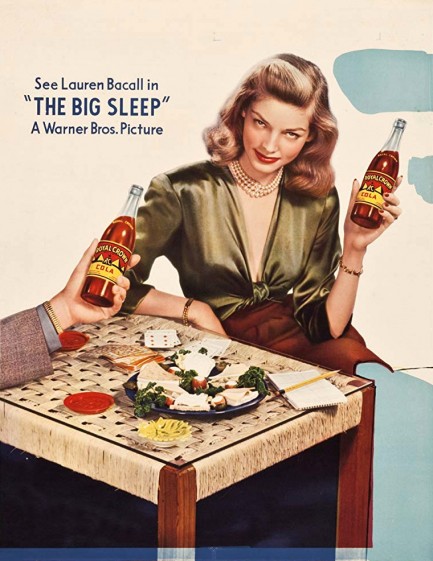

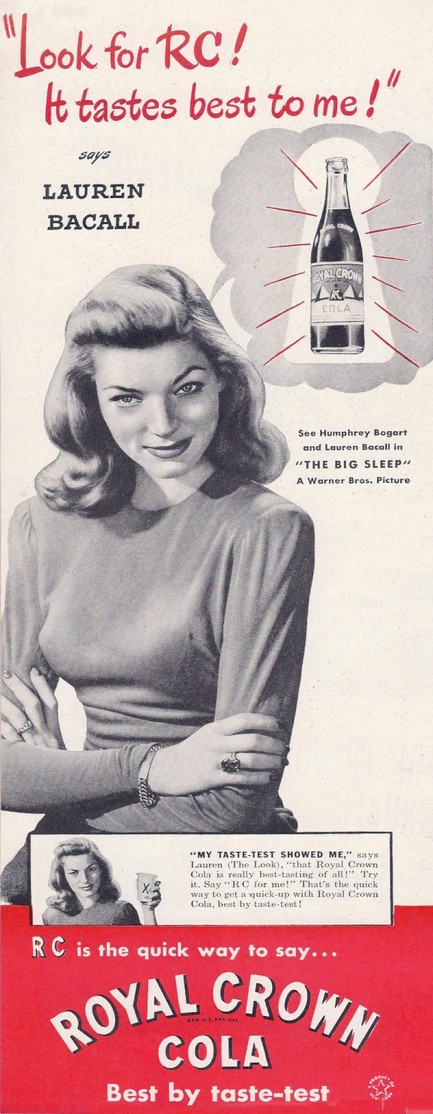

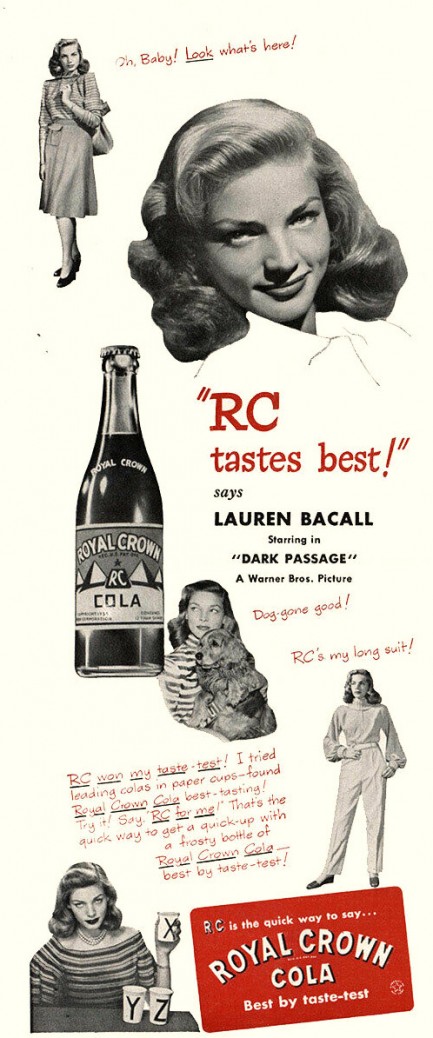

Royal Crown helps consumers to stay awake at the movies.

Lauren Bacall brings her special brand of smoky sex appeal to this magazine advertisement for Royal Crown Cola, made as a tie-in with her 1946 film noir The Big Sleep. RC was launched in 1905 by Union Bottling Works—a grandiose corporate name for some guys in the back of a Georgia grocery store. The story is that the drink came into being after grocer Claud A. Hatcher got into a feud with his Coca Cola supplier over the cost of Coke syrup, and essentially launched RC out of equal parts entrepreneurialism and spite. Union Bottling Works quickly had a line of drinks, including ginger ale, strawberry soda, and root beer.

However humbly RC Cola began, the upstart had truly arrived by 1946, because The Big Sleep, co-starring Humphrey Bogart, was an important movie, and Bacall was a huge star. She was only one jewel in the crown of RC's endorsement efforts. Also appearing in ads were Rita Hayworth, Veronica Lake, Joan Crawford, Virginia Mayo, Paulette Goddard, Gene Tierney, Ann Rutherford, Ginger Rogers, and others. Bacall flogged RC for at least a few years, including starring in tie-in ads for Dark Passage, another screen pairing of her and Bogart that hit cinemas in 1947. You see one of those at bottom. We can only assume these ads were wildly successful. After all, it was Bacall.

It's shocking how many Hollywood stars did smack.

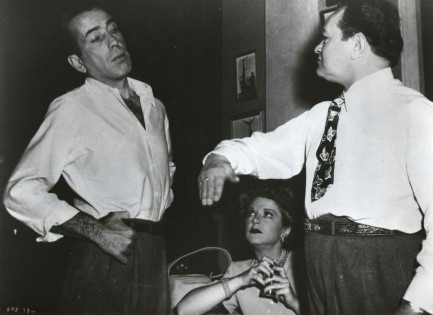

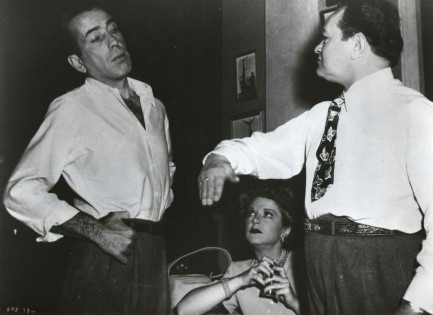

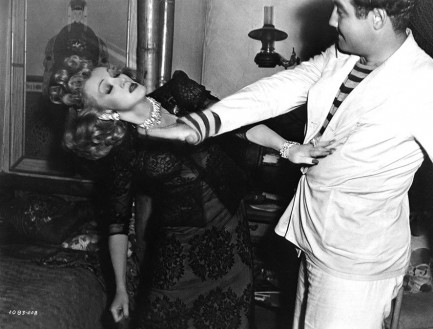

Everybody wants to slap somebody sometime. Luckily, actors in movies do it so you don't have to. The above shot is a good example. Edward G. Robinson lets Humphrey Bogart have it in 1948's Key Largo, as Claire Trevor looks on. In vintage cinema, people were constantly slapping. Men slapped men, men slapped women, women slapped women, and women slapped men. The recipient was usually the protagonist because—though some readers may not realize this—even during the ’40s and 50s, slapping was considered uncouth at a minimum, and downright villainous at worst, particularly when men did it. So generally, bad guys did the slapping, with some exceptions. Glenn Ford slaps Rita Hayworth in Gilda, for example, out of humiliation. Still wrong, but he wasn't the film's villain is our point. Humphrey Bogart lightly slaps Martha Vickers in The Big Sleep to bring her out of a drug stupor. He's like a doctor. Sort of. In any case, most cinematic slapping is fake, and when it wasn't it was done with the consent of the participants (No, really slap me! It'll look more realistic.). There are some famous examples of chipped teeth and bloody noses deriving from the pursuit of realism. We can envision a museum exhibit of photos like these, followed by a lot of conversation around film, social mores, masculinity, and their intersection. We can also envison a conversation around the difference between fantasy and reality. There are some who believe portryals of bad things endorse the same. But movies succeed largely by thrilling, shocking, and scaring audiences, which requires portraying thrilling, shocking, and frightening moments. If actors can't do that, then ultimately movies must become as banal as everyday llife. Enjoy the slapfest.

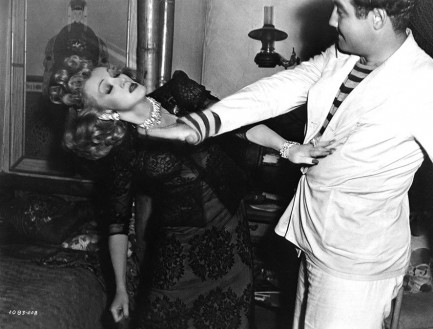

Broderick Crawford slaps Marlene Dietrich in the 1940's Seven Sinners. Broderick Crawford slaps Marlene Dietrich in the 1940's Seven Sinners.

June Allyson lets Joan Collins have it across the kisser in a promo image for The Opposite Sex, 1956. June Allyson lets Joan Collins have it across the kisser in a promo image for The Opposite Sex, 1956.

Speaking of Gilda, here's one of Glenn Ford and Rita Hayworth re-enacting the slap heard round the world. Hayworth gets to slap Ford too, and according to some accounts she loosened two of his teeth. We don't know if that's true, but if you watch the sequence it is indeed quite a blow. 100% real. We looked for a photo of it but had no luck. Speaking of Gilda, here's one of Glenn Ford and Rita Hayworth re-enacting the slap heard round the world. Hayworth gets to slap Ford too, and according to some accounts she loosened two of his teeth. We don't know if that's true, but if you watch the sequence it is indeed quite a blow. 100% real. We looked for a photo of it but had no luck.

Don't mess with box office success. Ford and Hayworth did it again in 1952's Affair in Trinidad. Don't mess with box office success. Ford and Hayworth did it again in 1952's Affair in Trinidad.

All-time film diva Joan Crawford gets in a good shot on Lucy Marlow in 1955's Queen Bee. All-time film diva Joan Crawford gets in a good shot on Lucy Marlow in 1955's Queen Bee.

The answer to the forthcoming question is: She turned into a human monster, that's what. Joan Crawford is now on the receiving end, with Bette Davis issuing the slap in Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? Later Davis kicks Crawford, so the slap is just a warm-up. The answer to the forthcoming question is: She turned into a human monster, that's what. Joan Crawford is now on the receiving end, with Bette Davis issuing the slap in Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? Later Davis kicks Crawford, so the slap is just a warm-up.

Mary Murphy awaits the inevitable from John Payne in 1955's Hell's Island. Mary Murphy awaits the inevitable from John Payne in 1955's Hell's Island.

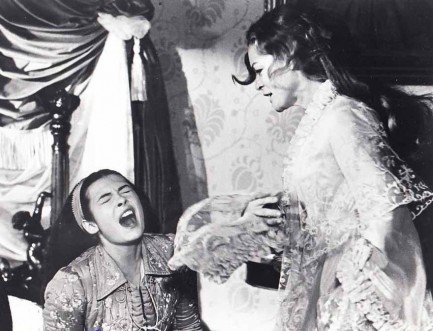

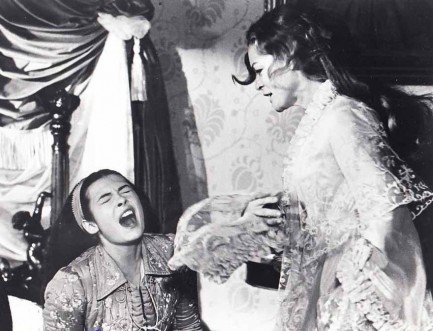

Romy Schneider slaps Sonia Petrova in 1972's Ludwig. Romy Schneider slaps Sonia Petrova in 1972's Ludwig.

Lauren Bacall lays into Charles Boyer in 1945's Confidential Agent and garnishes the slap with a brilliant snarl. Lauren Bacall lays into Charles Boyer in 1945's Confidential Agent and garnishes the slap with a brilliant snarl.

Iconic bombshell Marilyn Monroe drops a smart bomb on Cary Grant in the 1952 comedy Monkey Business. Iconic bombshell Marilyn Monroe drops a smart bomb on Cary Grant in the 1952 comedy Monkey Business.

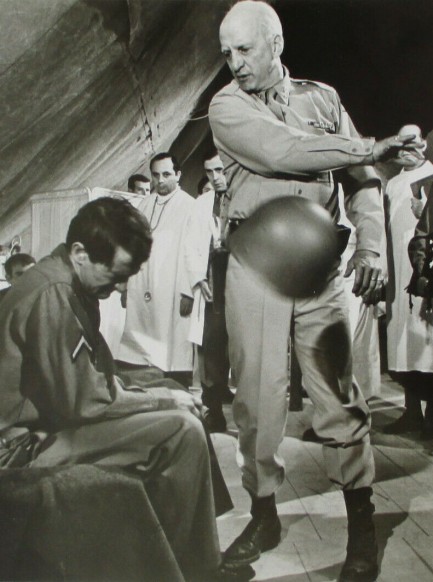

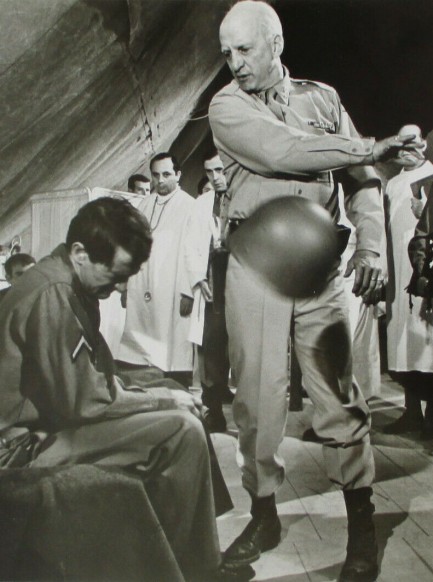

This is the most brutal slap of the bunch, we think, from 1969's Patton, as George C. Scott de-helmets an unfortunate soldier played by Tim Considine. This is the most brutal slap of the bunch, we think, from 1969's Patton, as George C. Scott de-helmets an unfortunate soldier played by Tim Considine.

A legendary scene in filmdom is when James Cagney shoves a grapefruit in Mae Clark's face in The Public Enemy. Is it a slap? He does it pretty damn hard, so we think it's close enough. They re-enact that moment here in a promo photo made in 1931. A legendary scene in filmdom is when James Cagney shoves a grapefruit in Mae Clark's face in The Public Enemy. Is it a slap? He does it pretty damn hard, so we think it's close enough. They re-enact that moment here in a promo photo made in 1931.

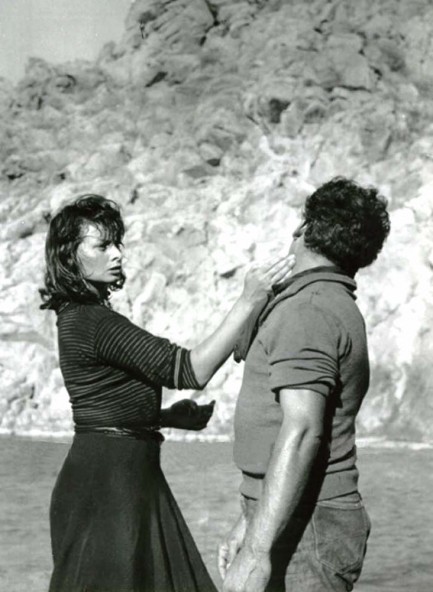

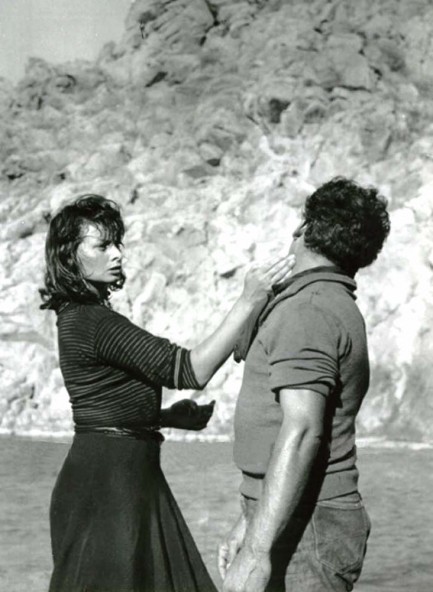

Sophia Loren gives Jorge Mistral a scenic seaside slap in 1957's Boy on a Dolphin. Sophia Loren gives Jorge Mistral a scenic seaside slap in 1957's Boy on a Dolphin.

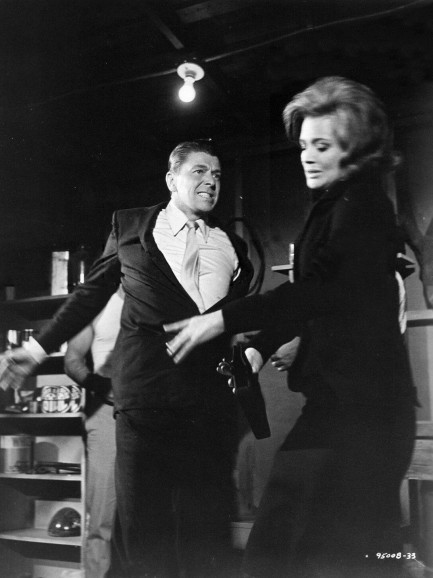

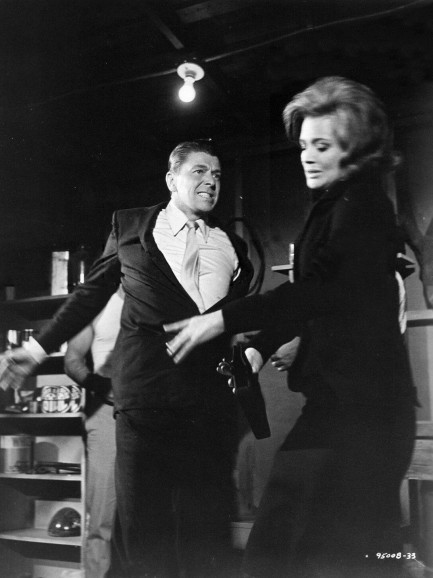

Victor Mature fails to live up to his last name as he slaps Lana Turner in 1954's Betrayed. Victor Mature fails to live up to his last name as he slaps Lana Turner in 1954's Betrayed.  Ronald Reagan teaches Angie Dickinson how supply side economics work in 1964's The Killers. Ronald Reagan teaches Angie Dickinson how supply side economics work in 1964's The Killers.

Marie Windsor gets in one against Mary Castle from the guard position in an episode of television's Stories of the Century in 1954. Windsor eventually won this bout with a rear naked choke. Marie Windsor gets in one against Mary Castle from the guard position in an episode of television's Stories of the Century in 1954. Windsor eventually won this bout with a rear naked choke.

It's better to give than receive, but sadly it's Bette Davis's turn, as she takes one from Dennis Morgan in In This Our Life, 1942. It's better to give than receive, but sadly it's Bette Davis's turn, as she takes one from Dennis Morgan in In This Our Life, 1942.

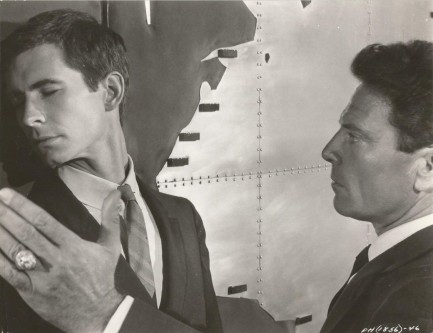

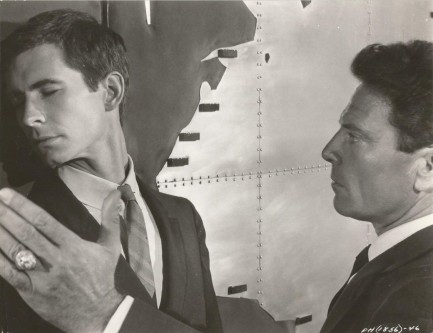

Anthony Perkins and Raf Vallone dance the dance in 1962's Phaedra, with Vallone taking the lead. Anthony Perkins and Raf Vallone dance the dance in 1962's Phaedra, with Vallone taking the lead.

And he thought being inside the ring was hard. Lilli Palmer nails John Garfield with a roundhouse right in the 1947 boxing classic Body and Soul. And he thought being inside the ring was hard. Lilli Palmer nails John Garfield with a roundhouse right in the 1947 boxing classic Body and Soul.

1960's Il vigile, aka The Mayor, sees Vittorio De Sica rebuked by a member of the electorate Lia Zoppelli. She's more than a voter in this—she's also his wife, so you can be sure he deserved it. 1960's Il vigile, aka The Mayor, sees Vittorio De Sica rebuked by a member of the electorate Lia Zoppelli. She's more than a voter in this—she's also his wife, so you can be sure he deserved it.

Brigitte Bardot delivers a not-so-private slap to Dirk Sanders in 1962's Vie privée, aka A Very Private Affair. Brigitte Bardot delivers a not-so-private slap to Dirk Sanders in 1962's Vie privée, aka A Very Private Affair.

In a classic case of animal abuse. Judy Garland gives cowardly lion Bert Lahr a slap on the nose in The Wizard of Oz. Is it his fault he's a pussy? Accept him as he is, Judy. In a classic case of animal abuse. Judy Garland gives cowardly lion Bert Lahr a slap on the nose in The Wizard of Oz. Is it his fault he's a pussy? Accept him as he is, Judy.

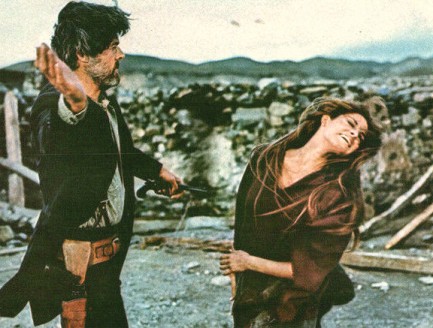

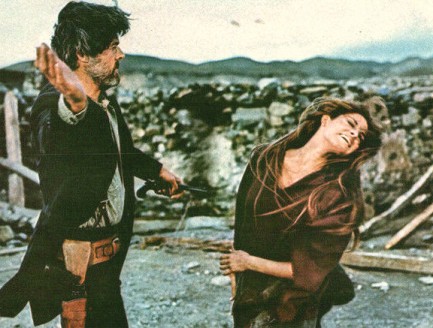

Robert Culp backhands Raquel Welch in 1971's Hannie Caudler. Robert Culp backhands Raquel Welch in 1971's Hannie Caudler.

And finally, Laurence Harvey dares to lay hands on the perfect Kim Novak in Of Human Bondage. And finally, Laurence Harvey dares to lay hands on the perfect Kim Novak in Of Human Bondage.

The eyes have it in for you.

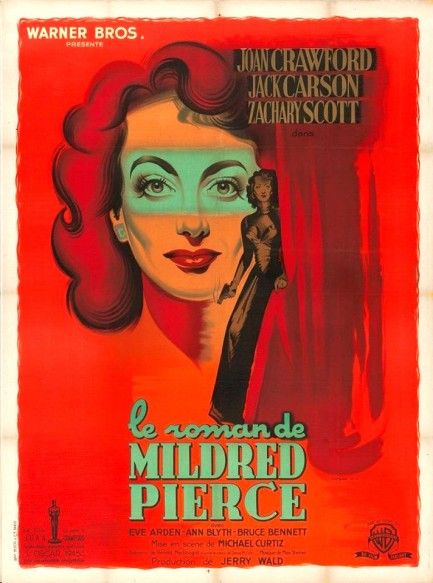

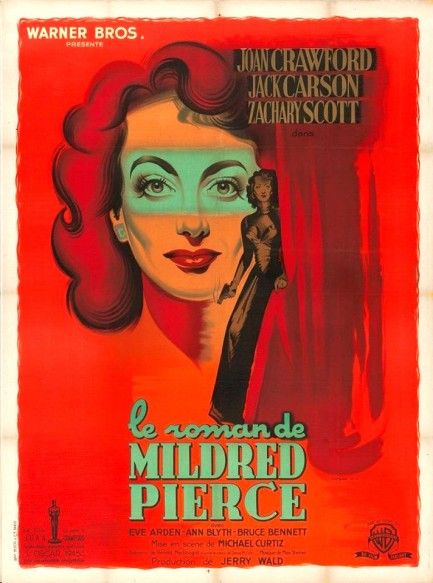

Above, a beautiful promo poster for the film noir Mildred Pierce made for the film's run in France, which began today in 1947, more than a year after its U.S. premiere. This is pure awesomeness from artist Roger Rojac. Note that it touts Joan Crawford's Academy Award triumph, her win as best actress. It was also nominated for best picture but beaten by Lost Weekend, which is these days considered a bit of a cheeseball classic. We have our earlier write-up on Mildred Pierce here, and a nice promo image for the film at this link.

Spare the rod, spoil the child.

We ran across this West German poster for Solange ein herz schlaegt, aka Mildred Pierce, and realized we had a substantial gap in our film noir résumé. So we watched the movie, and what struck us about it immediately is that it opens with a shooting. Not a lead-in to a shooting, but the shooting itself—fade in, bang bang, guy falls dead. These days most thrillers bludgeon audiences with big openings like that, but back in the day such action beats typically came mid- and late-film. So we were surprised by that. What we weren't surprised by was that Mildred Pierce is good. It's based on a James M. Cain novel, is directed by Michael Curtiz, and is headlined by Joan Crawford. These were top talents in writing, directing, and acting, which means the acclaim associated with the movie is deserved.

While Mildred Pierce is a mystery thriller it's also a family drama revolving around a twice-married woman's dysfunctional relationship with her gold-digging elder daughter, whose desperation to escape her working class roots leads her to make some very bad decisions. Her mother, trying to make her daughter happy, makes even worse decisions. The movie isn't perfect—for one, the daughter's feverish obsession with money seems extreme considering family financial circumstances continuously improve; and as in many movies of the period, the only black character is used as cringingly unkind comic relief. But those blemishes aside, this one is enjoyable, even if the central mystery isn't really much of a mystery. Solange ein herz schlaegt, aka Mildred Pierce opened in West Germany today in 1950.

|

|

The headlines that mattered yesteryear.

2003—Hope Dies

Film legend Bob Hope dies of pneumonia two months after celebrating his 100th birthday. 1945—Churchill Given the Sack

In spite of admiring Winston Churchill as a great wartime leader, Britons elect

Clement Attlee the nation's new prime minister in a sweeping victory for the Labour Party over the Conservatives. 1952—Evita Peron Dies

Eva Duarte de Peron, aka Evita, wife of the president of the Argentine Republic, dies from cancer at age 33. Evita had brought the working classes into a position of political power never witnessed before, but was hated by the nation's powerful military class. She is lain to rest in Milan, Italy in a secret grave under a nun's name, but is eventually returned to Argentina for reburial beside her husband in 1974. 1943—Mussolini Calls It Quits

Italian dictator Benito Mussolini steps down as head of the armed forces and the government. It soon becomes clear that Il Duce did not relinquish power voluntarily, but was forced to resign after former Fascist colleagues turned against him. He is later installed by Germany as leader of the Italian Social Republic in the north of the country, but is killed by partisans in 1945.

|

|

|

It's easy. We have an uploader that makes it a snap. Use it to submit your art, text, header, and subhead. Your post can be funny, serious, or anything in between, as long as it's vintage pulp. You'll get a byline and experience the fleeting pride of free authorship. We'll edit your post for typos, but the rest is up to you. Click here to give us your best shot.

|

|

Hi, take a real good look at me, baby, because I'll be your stalker.

Hi, take a real good look at me, baby, because I'll be your stalker. See? Stalking. Here I am in your kitchen this morning without permission.

See? Stalking. Here I am in your kitchen this morning without permission. Surprise! Stalking! This time I swam all the way across the bay to stalk you.

Surprise! Stalking! This time I swam all the way across the bay to stalk you.

Lovely calves. Shapely but not too developed. Which means you won't be able to outrun me.

Lovely calves. Shapely but not too developed. Which means you won't be able to outrun me. Is this your diary? I'm gonna read it. I know—presumptuous as hell, right?

Is this your diary? I'm gonna read it. I know—presumptuous as hell, right? Wow. You write that I'm a walking vomit stain with sadistic eyes, the manners of a crocodile, and a bulge in my swimsuit the size of a wine cork.

Wow. You write that I'm a walking vomit stain with sadistic eyes, the manners of a crocodile, and a bulge in my swimsuit the size of a wine cork. You've been looking at my bulge, eh?

You've been looking at my bulge, eh? I hate you, lady. That's reverse psychology. It's right out of the stalker's handbook.

I hate you, lady. That's reverse psychology. It's right out of the stalker's handbook. Not so fast, Joan. What do you take me for? Let the delicious irony stretch out a little. In fact, maybe I won't even kiss you. That'd teach you.

Not so fast, Joan. What do you take me for? Let the delicious irony stretch out a little. In fact, maybe I won't even kiss you. That'd teach you. Just kidding. Let's do this. Tonsils here I come.

Just kidding. Let's do this. Tonsils here I come. There's something about that man...

There's something about that man...

Broderick Crawford slaps Marlene Dietrich in the 1940's Seven Sinners.

Broderick Crawford slaps Marlene Dietrich in the 1940's Seven Sinners. June Allyson lets Joan Collins have it across the kisser in a promo image for The Opposite Sex, 1956.

June Allyson lets Joan Collins have it across the kisser in a promo image for The Opposite Sex, 1956. Speaking of Gilda, here's one of Glenn Ford and Rita Hayworth re-enacting the slap heard round the world. Hayworth gets to slap Ford too, and according to some accounts she loosened two of his teeth. We don't know if that's true, but if you watch the sequence it is indeed quite a blow. 100% real. We looked for a photo of it but had no luck.

Speaking of Gilda, here's one of Glenn Ford and Rita Hayworth re-enacting the slap heard round the world. Hayworth gets to slap Ford too, and according to some accounts she loosened two of his teeth. We don't know if that's true, but if you watch the sequence it is indeed quite a blow. 100% real. We looked for a photo of it but had no luck. Don't mess with box office success. Ford and Hayworth did it again in 1952's Affair in Trinidad.

Don't mess with box office success. Ford and Hayworth did it again in 1952's Affair in Trinidad. All-time film diva Joan Crawford gets in a good shot on Lucy Marlow in 1955's Queen Bee.

All-time film diva Joan Crawford gets in a good shot on Lucy Marlow in 1955's Queen Bee. The answer to the forthcoming question is: She turned into a human monster, that's what. Joan Crawford is now on the receiving end, with Bette Davis issuing the slap in Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? Later Davis kicks Crawford, so the slap is just a warm-up.

The answer to the forthcoming question is: She turned into a human monster, that's what. Joan Crawford is now on the receiving end, with Bette Davis issuing the slap in Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? Later Davis kicks Crawford, so the slap is just a warm-up. Mary Murphy awaits the inevitable from John Payne in 1955's Hell's Island.

Mary Murphy awaits the inevitable from John Payne in 1955's Hell's Island. Romy Schneider slaps Sonia Petrova in 1972's Ludwig.

Romy Schneider slaps Sonia Petrova in 1972's Ludwig. Lauren Bacall lays into Charles Boyer in 1945's Confidential Agent and garnishes the slap with a brilliant snarl.

Lauren Bacall lays into Charles Boyer in 1945's Confidential Agent and garnishes the slap with a brilliant snarl. Iconic bombshell Marilyn Monroe drops a smart bomb on Cary Grant in the 1952 comedy Monkey Business.

Iconic bombshell Marilyn Monroe drops a smart bomb on Cary Grant in the 1952 comedy Monkey Business. This is the most brutal slap of the bunch, we think, from 1969's Patton, as George C. Scott de-helmets an unfortunate soldier played by Tim Considine.

This is the most brutal slap of the bunch, we think, from 1969's Patton, as George C. Scott de-helmets an unfortunate soldier played by Tim Considine. A legendary scene in filmdom is when James Cagney shoves a grapefruit in Mae Clark's face in The Public Enemy. Is it a slap? He does it pretty damn hard, so we think it's close enough. They re-enact that moment here in a promo photo made in 1931.

A legendary scene in filmdom is when James Cagney shoves a grapefruit in Mae Clark's face in The Public Enemy. Is it a slap? He does it pretty damn hard, so we think it's close enough. They re-enact that moment here in a promo photo made in 1931. Sophia Loren gives Jorge Mistral a scenic seaside slap in 1957's Boy on a Dolphin.

Sophia Loren gives Jorge Mistral a scenic seaside slap in 1957's Boy on a Dolphin. Victor Mature fails to live up to his last name as he slaps Lana Turner in 1954's Betrayed.

Victor Mature fails to live up to his last name as he slaps Lana Turner in 1954's Betrayed. Ronald Reagan teaches Angie Dickinson how supply side economics work in 1964's The Killers.

Ronald Reagan teaches Angie Dickinson how supply side economics work in 1964's The Killers. Marie Windsor gets in one against Mary Castle from the guard position in an episode of television's Stories of the Century in 1954. Windsor eventually won this bout with a rear naked choke.

Marie Windsor gets in one against Mary Castle from the guard position in an episode of television's Stories of the Century in 1954. Windsor eventually won this bout with a rear naked choke. It's better to give than receive, but sadly it's Bette Davis's turn, as she takes one from Dennis Morgan in In This Our Life, 1942.

It's better to give than receive, but sadly it's Bette Davis's turn, as she takes one from Dennis Morgan in In This Our Life, 1942. Anthony Perkins and Raf Vallone dance the dance in 1962's Phaedra, with Vallone taking the lead.

Anthony Perkins and Raf Vallone dance the dance in 1962's Phaedra, with Vallone taking the lead. And he thought being inside the ring was hard. Lilli Palmer nails John Garfield with a roundhouse right in the 1947 boxing classic Body and Soul.

And he thought being inside the ring was hard. Lilli Palmer nails John Garfield with a roundhouse right in the 1947 boxing classic Body and Soul. 1960's Il vigile, aka The Mayor, sees Vittorio De Sica rebuked by a member of the electorate Lia Zoppelli. She's more than a voter in this—she's also his wife, so you can be sure he deserved it.

1960's Il vigile, aka The Mayor, sees Vittorio De Sica rebuked by a member of the electorate Lia Zoppelli. She's more than a voter in this—she's also his wife, so you can be sure he deserved it. Brigitte Bardot delivers a not-so-private slap to Dirk Sanders in 1962's Vie privée, aka A Very Private Affair.

Brigitte Bardot delivers a not-so-private slap to Dirk Sanders in 1962's Vie privée, aka A Very Private Affair. In a classic case of animal abuse. Judy Garland gives cowardly lion Bert Lahr a slap on the nose in The Wizard of Oz. Is it his fault he's a pussy? Accept him as he is, Judy.

In a classic case of animal abuse. Judy Garland gives cowardly lion Bert Lahr a slap on the nose in The Wizard of Oz. Is it his fault he's a pussy? Accept him as he is, Judy. Robert Culp backhands Raquel Welch in 1971's Hannie Caudler.

Robert Culp backhands Raquel Welch in 1971's Hannie Caudler. And finally, Laurence Harvey dares to lay hands on the perfect Kim Novak in Of Human Bondage.

And finally, Laurence Harvey dares to lay hands on the perfect Kim Novak in Of Human Bondage.