Eight! Nine! Nine and a half! Nine and five-eighths! Get up! I'm bought off but I can't be obvious! You think I'm a Supreme Court justice or something?

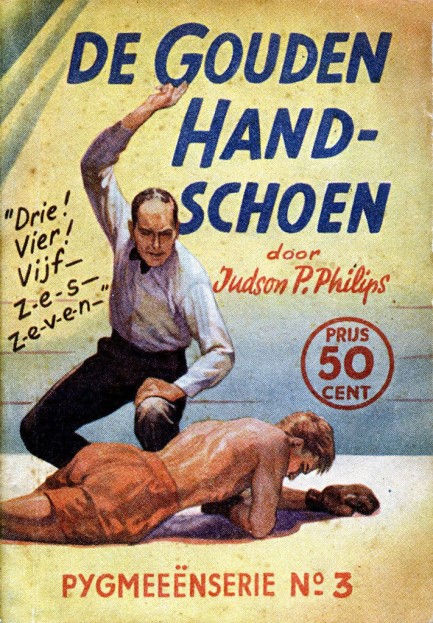

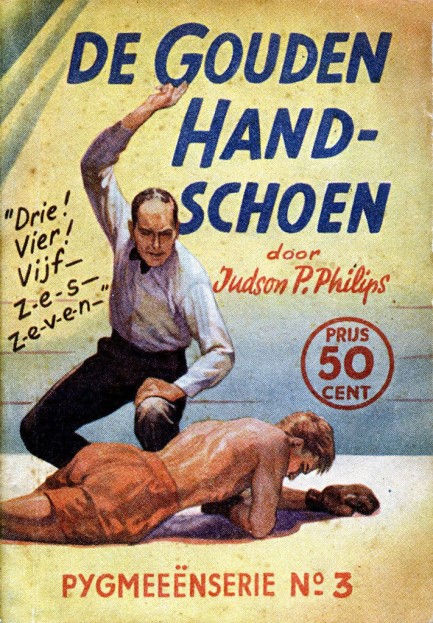

This Dutch paperback cover was painted by an unknown, but we love it. It fronts Judson P. Philips' De gouden handscheon. “Handschoen” is a pretty easy translation if you think literally—handshoe. But what the hell is a handshoe? *checking internet* In Dutch it means “glove.” Makes perfect sense. What do they call a condom? *checking internet* Sadly, it isn't “dickshoe.” Anyway, Philips was a pseudonym for Hugh Pentecost, and this was published by Uitgeverij de Combinatie in 1948.

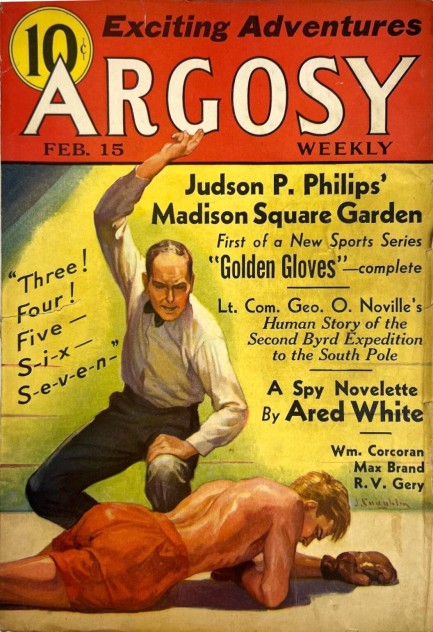

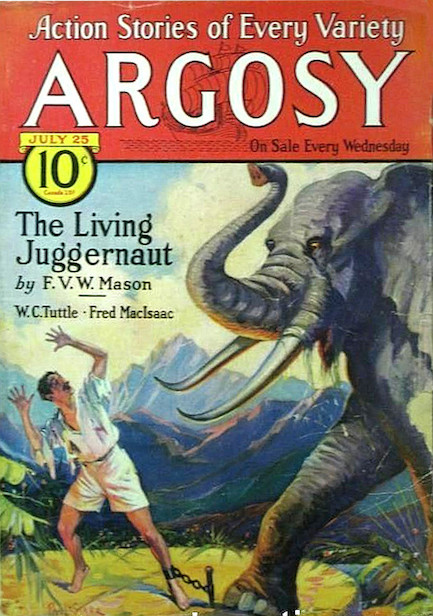

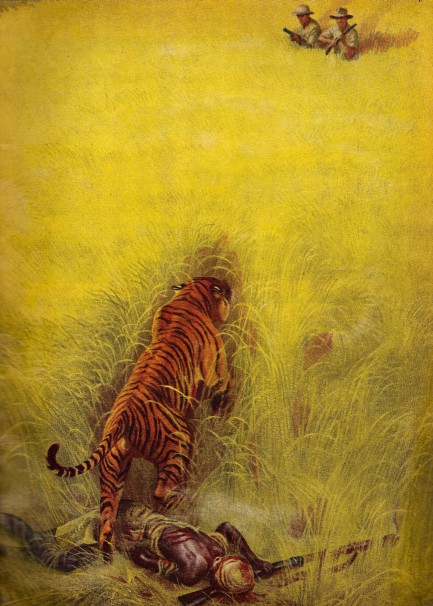

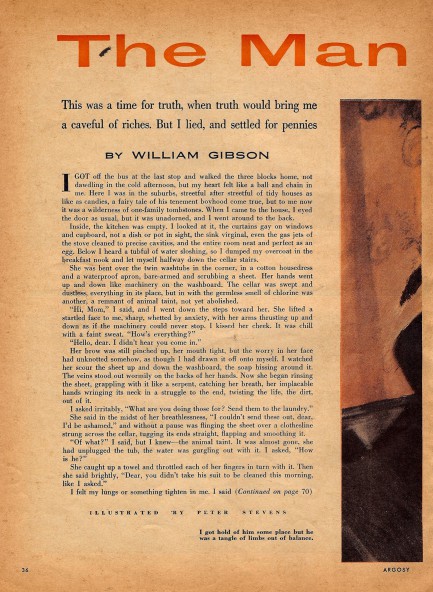

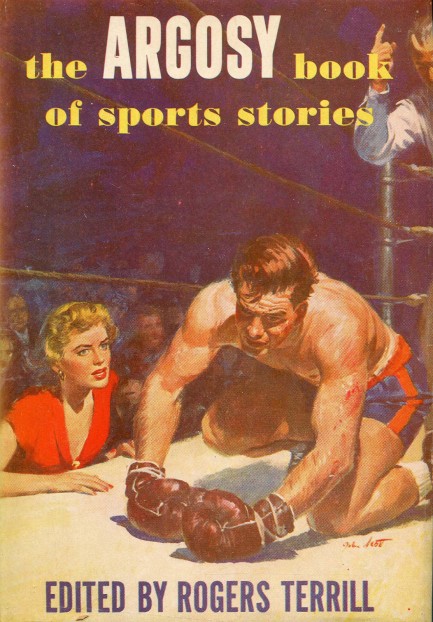

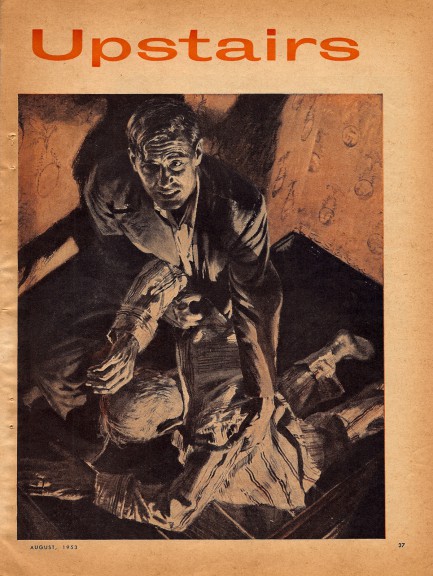

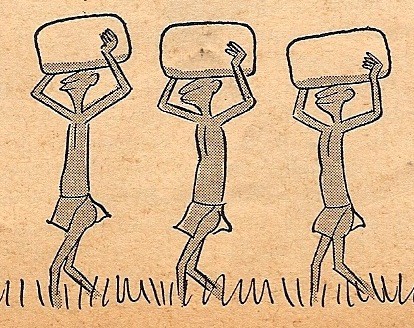

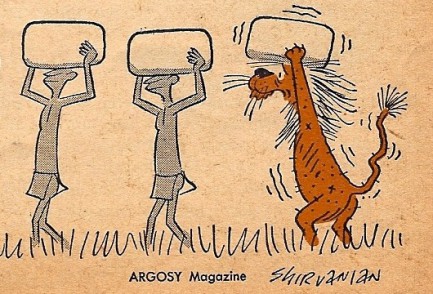

Update: Same day update, actually, which should give you an idea how much time we spend poking around for information. Turns out the above cover was adapted from a 1936 issue of the pulp magazine Argosy. The art is signed by John A. Coughlin. Also note that Judson P. Philips has a story in the issue. That leads to the reasonable conclusion that De gouden handschoen is a Dutch translation of that story typeset to paperback length.

Baby, stay down! I put a hundred bucks on the other guy!

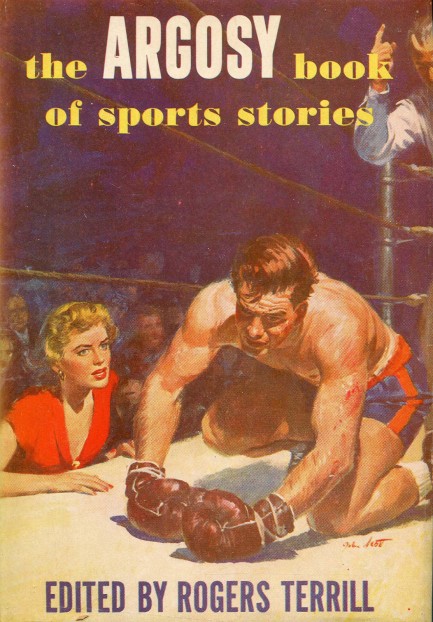

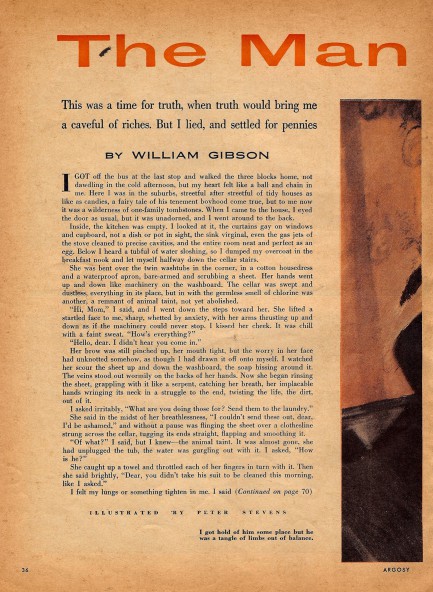

Argosy magazine, the first of the pulps, running from 1882 to 1978, occasionally compiled its sports related short stories into a long format publication, and you see an example here—The Argosy Book of Sports Stories. This edition with cover art by John Walter Scott was published in 1953 with stories from Virgil Scott, William Campbell Gault, William Holder, Stewart Sterling, Scott Young, and others. We stopped highlighting Argosy long ago because it has little visual content aside from the covers, but we discussed it several times, and you can those posts here, here, here, and here.

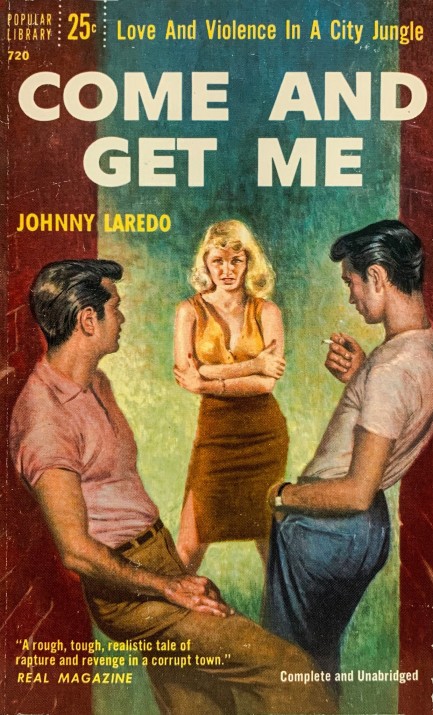

No, seriously. I said come and get me. Don't just stand there. Or... did I interrupt something?

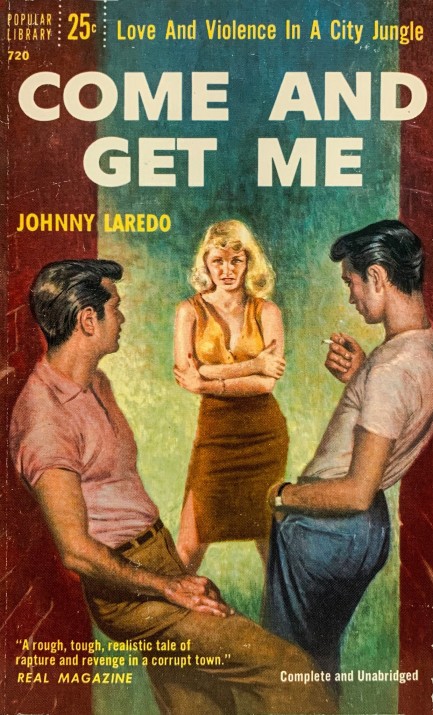

Above is a cover for Johnny Laredo's Come and Get Me, copyright 1956 from Popular Library. Think Laredo is a pseudonym? You think correctly. The publishers make a big deal out of keeping his real identity secret, writing a blurb inside the book calling Laredo, “the pseudonym of a young fiction writer whose stories have appeared in Argosy, The Virginia Quarterly Review, Cosmopolitan, and Bluebook.” Why an extensively published author wanted no credit for this book is a mystery, but the gig is up—he was Gene Caesar, a writer who had an affinity for westerns, but here crafted a crime drama about a man bent on avenging the murder of his girlfriend. The art, which we love because it can be interpreted a couple of ways, is by Raymond Johnson.

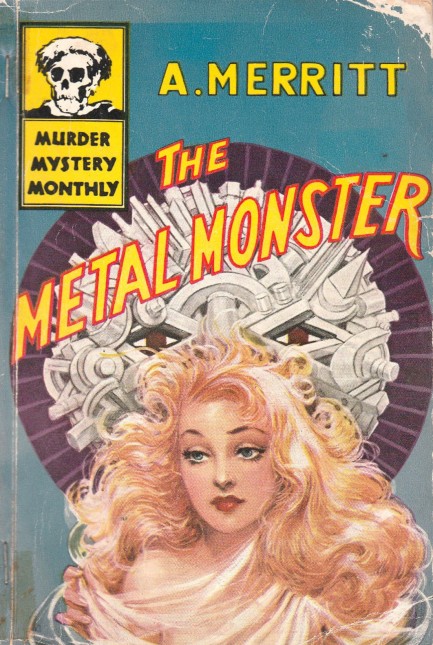

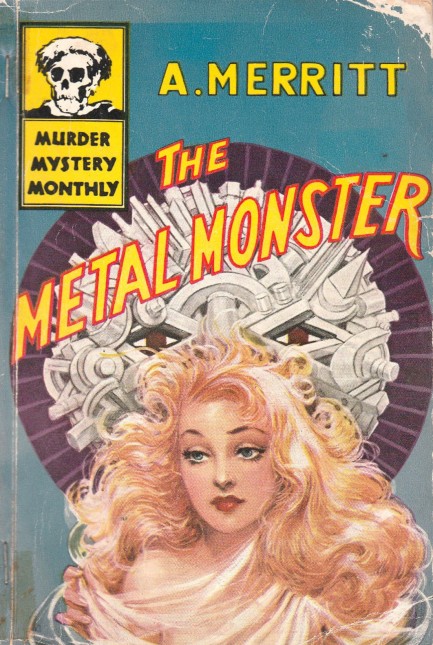

The Metal Monster is science fiction as a mind-altering trip.

We usually read novels from the ’40s, ’50s, and ’60s, but we took a trip to the heart of the pulp era with Abraham Merritt's The Metal Monster, which made its first appearance as a serial in Argosy All-Story Weekly in 1920. The above paperback came in 1946 from Avon Publications' Murder Mystery Monthly #41, and has cover art by the always interesting Paul Stahr, who worked extensively with Avon during this period. You can click his keywords at bottom and see all four of the covers by him we have in the website. There are also interesting covers by other artists on later editions of The Metal Monster. We'll try to show you a couple of those later. In Merritt's tale, four explorers travel into an uncharted Himalayan valley and subsequently are trapped by what lives in the area—Persian soldiers seemingly stuck in time, or whose traditions have gone unchanged for two thousand years. There's something else in the valley too—a shimmering goddess creature named Norhala and her metal swarm, which is usually a blizzard of small geometrical shapes, but can collect into forms as needed, for example a towering monster with six whiplike arms that scythe through the ranks of the Persians, ripping them to shreds. While Norhala has some control over the swarm, we later learn that the creatures came from the stars, feed on sunlight, and eventually eradicate biological life on every planet they colonize. So that's not good. Merritt's prose brings to mind H.P. Lovecraft, because he similarly tasks himself with describing the indescribable. Lovecraft fans know what that means—the creatures in his mythos are so mindbending as to drive humans insane merely to gaze upon them. Lovecraft challenged himself to describe those beings, and much of the horror in his writing derives from those attempts. But he sometimes took his built-in escape hatch too, ultimately saying the creatures simply were so inhuman they couldn't be described. Merritt faces the same challenge, and in his descriptions usually manages to be vivid yet vague: Where the azure globe had been, flashed out a disk of flaming splendors, the very secret soul of flowered flame! And simultaneously the pyramids leaped up and out behind it—two gigantic, four rayed stars blazing with cold blue fires. The green auroral curtainings flared out, ran with streaming radiance—as though some spirt of jewels had broken bonds of enchantment and burst forth jubilant, flooding the shaft with its freed glories. The tale is filled with psychedelia like the example above, though it does get more concrete in parts, like here: [They] lifted themselves in a thousand incredible shapes, shapes squared and globed and spiked and shifting swiftly into other thousands as incredible. I saw a mass of them draw themselves up into the likeness of a tent skyscraper high; hang so for an instant, then writhe into a monstrous chimera of a dozen towering legs that strode away like a gigantic headless and bodiless tarantula in steps two hundred feet long. I watched mile-long lines of them shape and reshape into circles, into interlaced lozenges and pentagons—then lift in great columns and shoot through the air in unimaginable barrage. Honestly, all these hyper-detailed descriptions get tedious at times, as does the pervasive incredulity of Merritt's narrator Dr. Walter T. Goodwin. We get that he's dumbfounded, but the human mind has an amazing capacity to normalize that which it sees constantly, therefore we'd prefer if Goodwin weren't repeatedly floored by everything he encounters. That way, when he finally learns what form the metal swarm actually takes—that of a vast city—we readers can finally be truly amazed. However, when we think of The Metal Monster as an Argosy serial circa 1920, it's visionary, and we imagine it must have been intensely gripping. Merritt may merit more exploration.

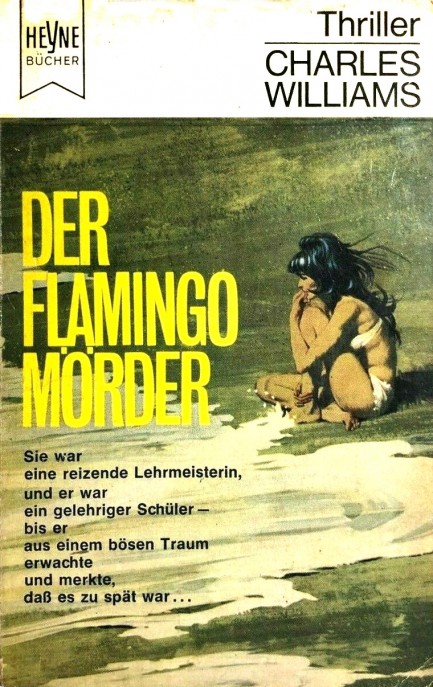

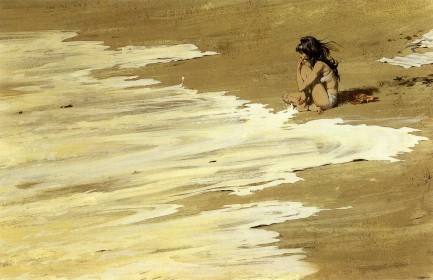

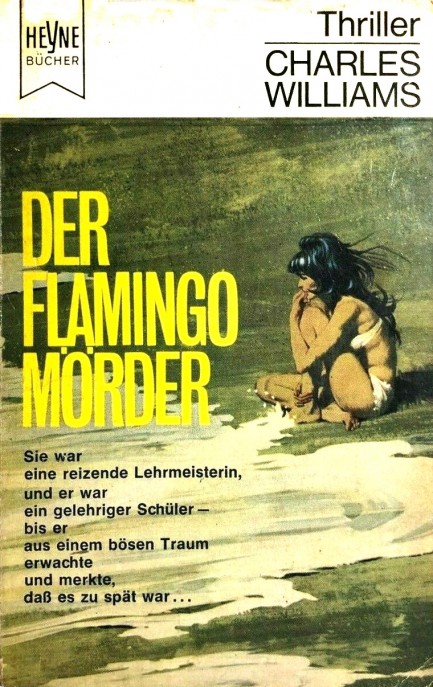

McGinnis sells sea tale with a seashore.

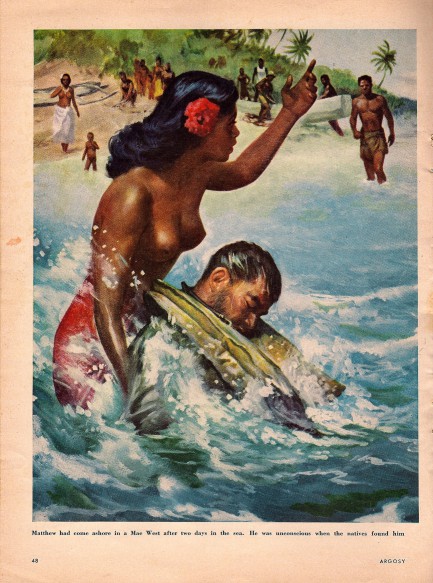

West German publishing company Heyne Bücher makes good use of art by Robert McGinnis on the cover of Der Flamingo Mörder, which was a translation of Charles Williams' 1958 novel The Concrete Flamingo, aka All the Way. This beachy painting originally appeared in Argosy in April 1961 as an illustration for Ed Lacy's story "The Naked Blanco,” but it's a perfect match for Williams, who became a gifted crafter of oceangoing thrillers, among them Dead Calm, And the Deep Blue Sea, Scorpion Reef, and Aground. And yes, we know, by the way, that technically (not even technically, but actually) a fowl is a bird domesticated for its eggs, which flamingos aren't, but you try thinking up headers for these posts for eleven straight years. Anyway, the entire McGinnis painting from which the cover art was borrowed is below. And as always you can learn more about everyone involved by clicking their keywords at bottom.

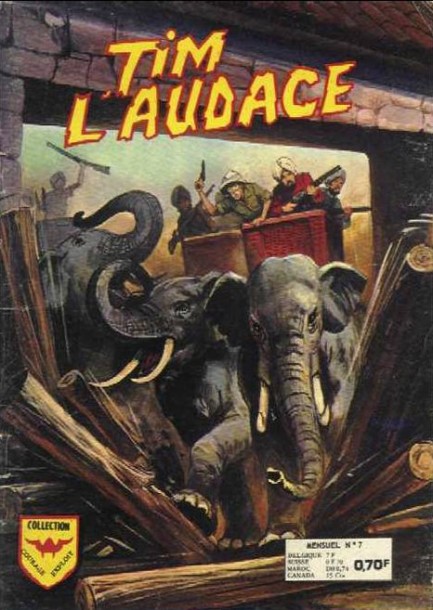

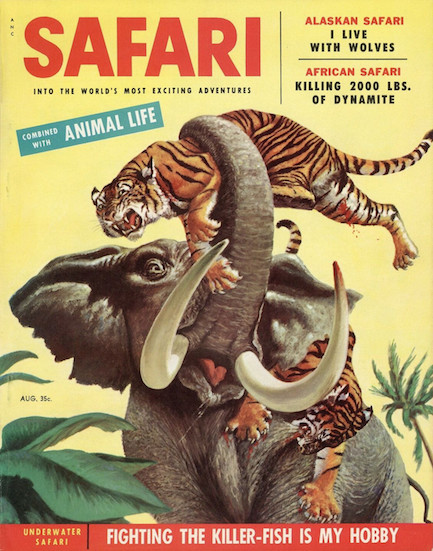

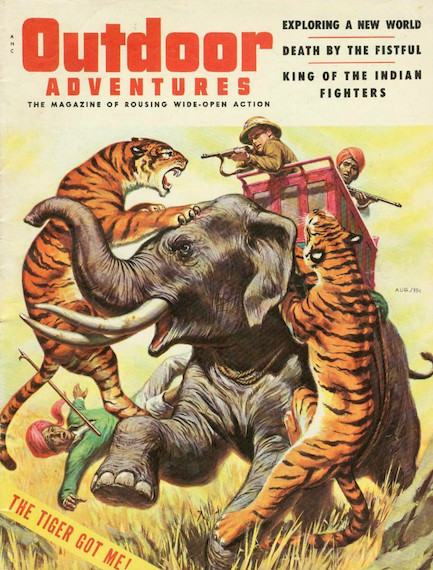

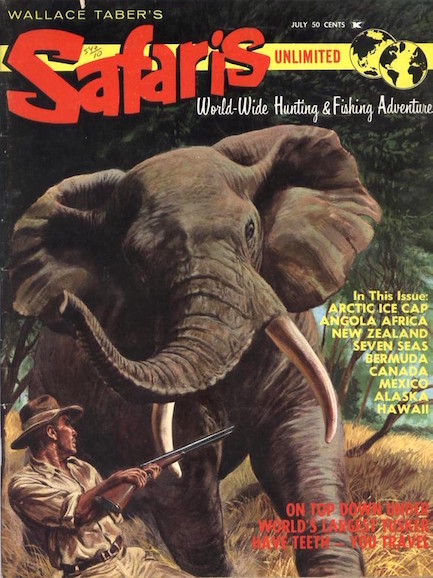

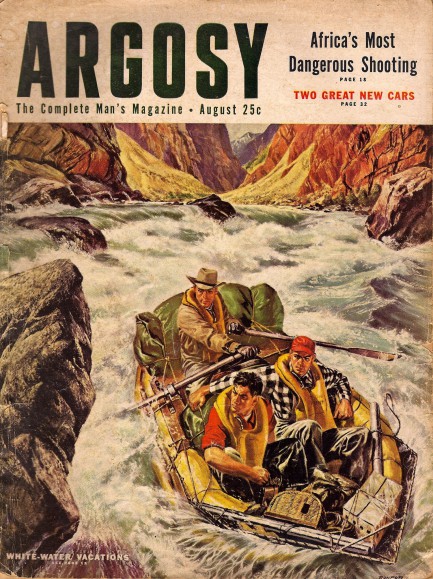

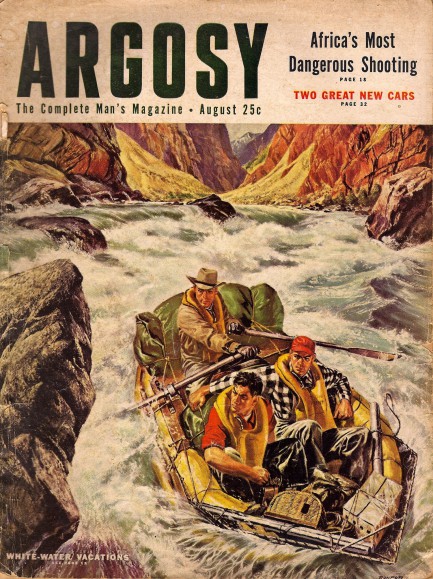

We’d hate to be in the same boat as these guys.

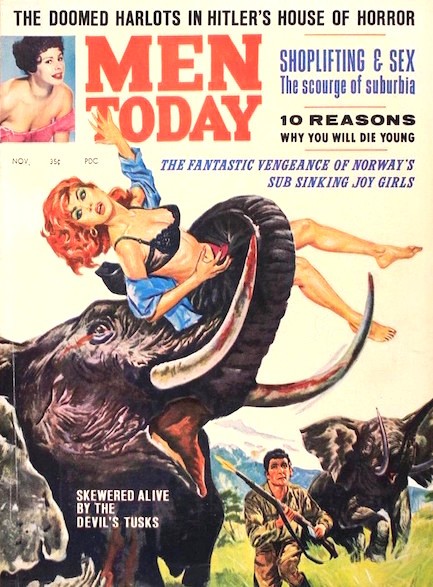

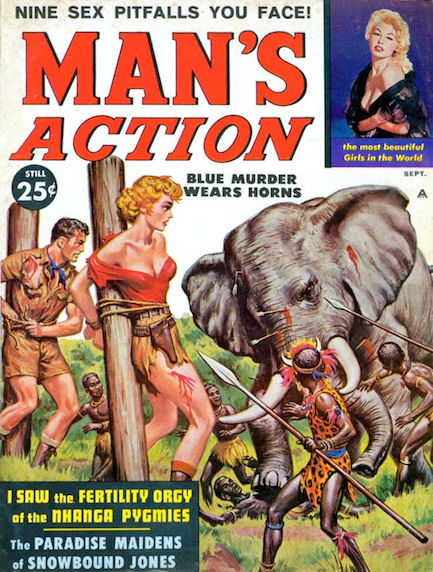

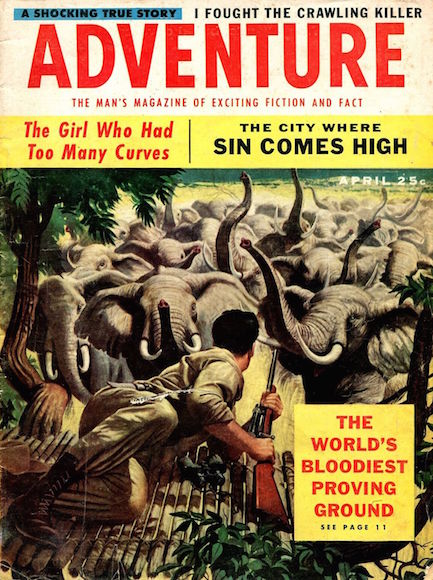

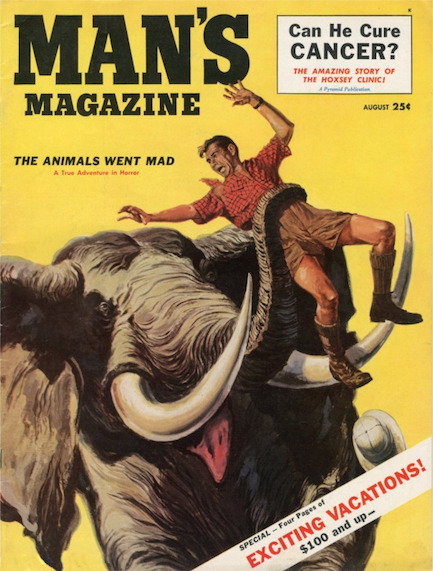

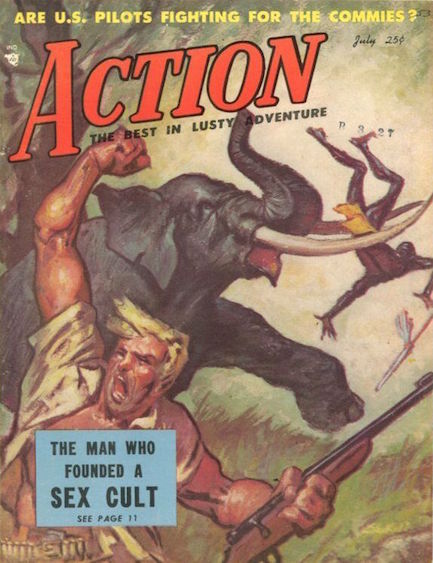

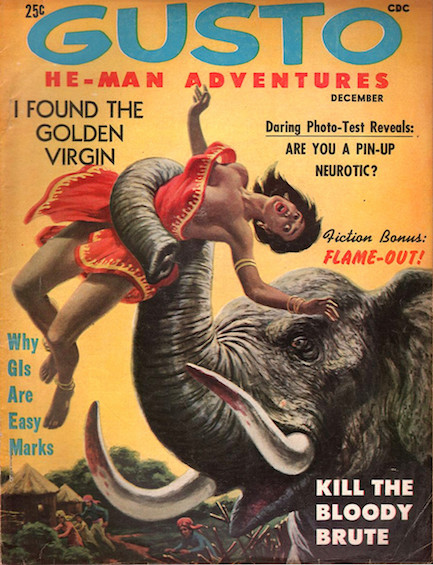

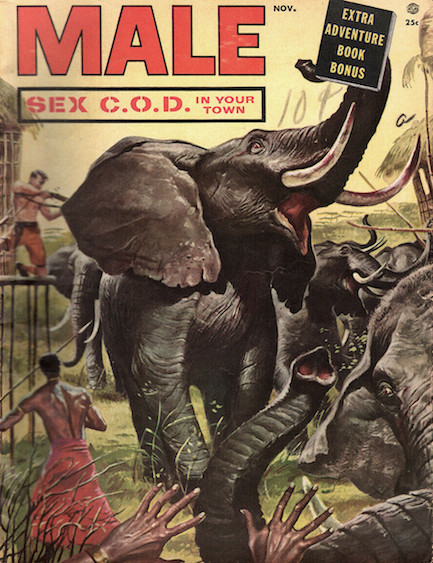

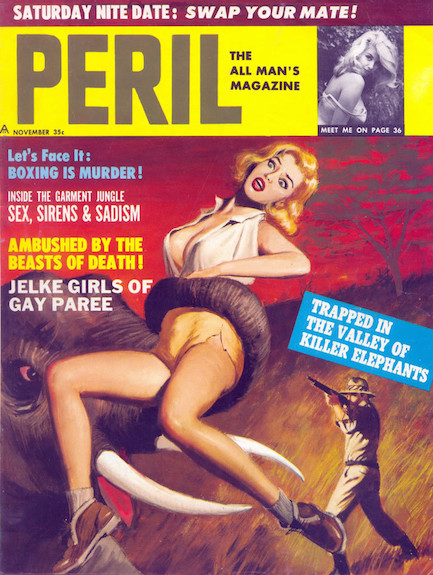

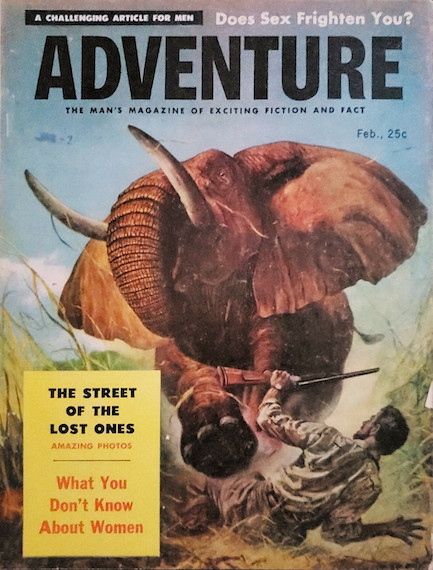

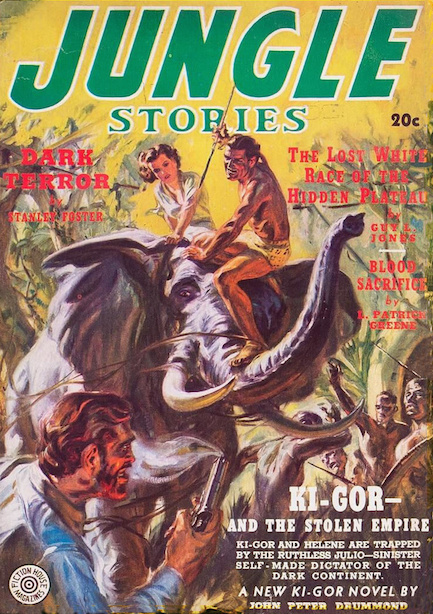

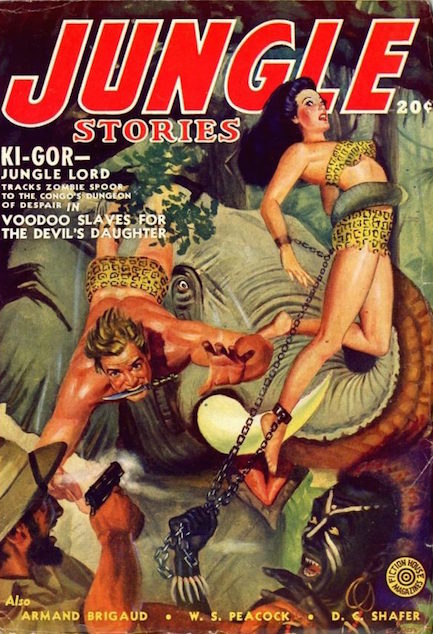

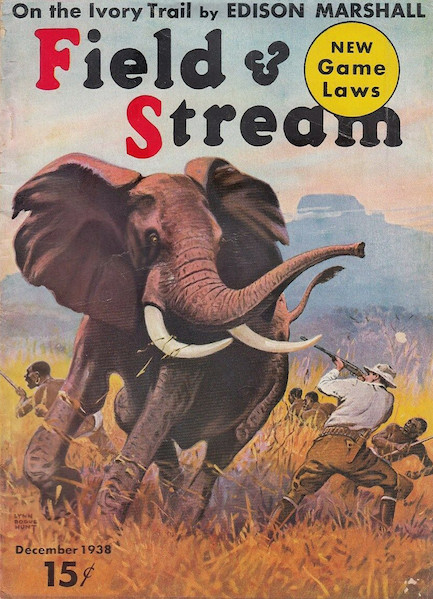

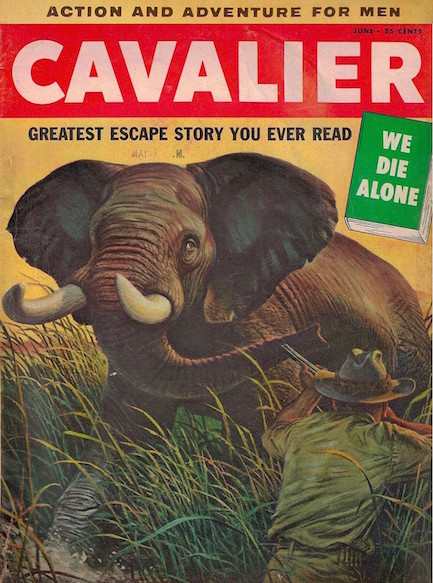

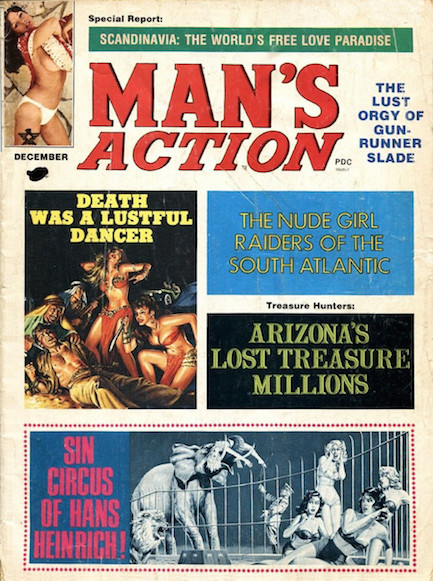

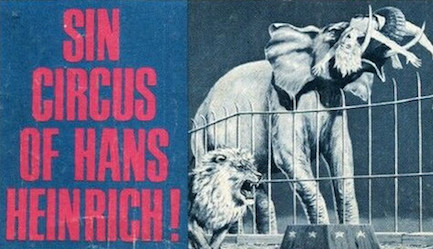

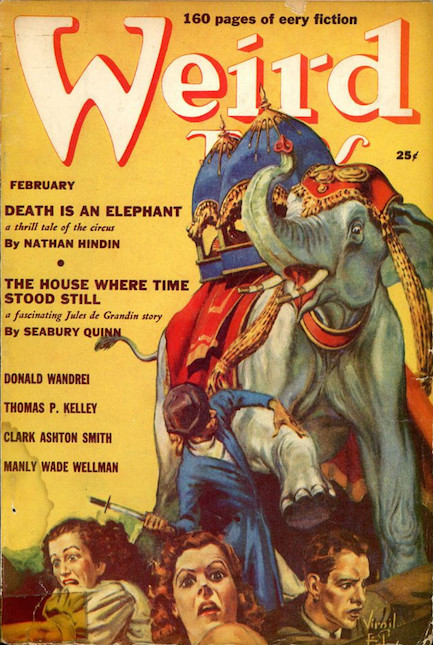

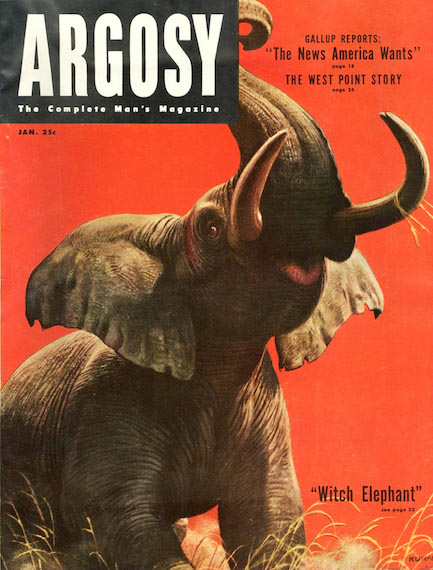

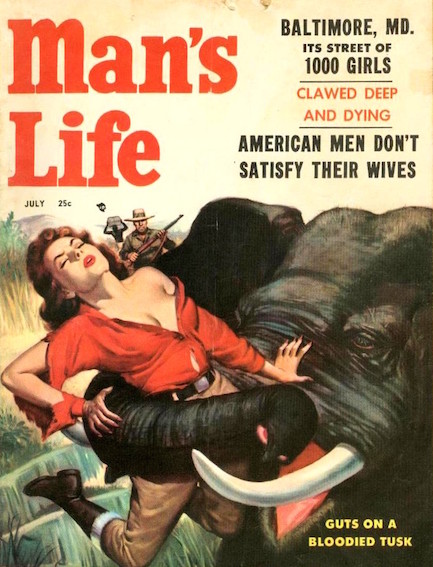

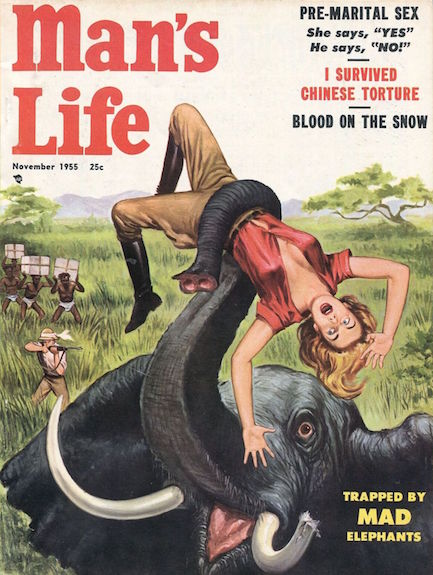

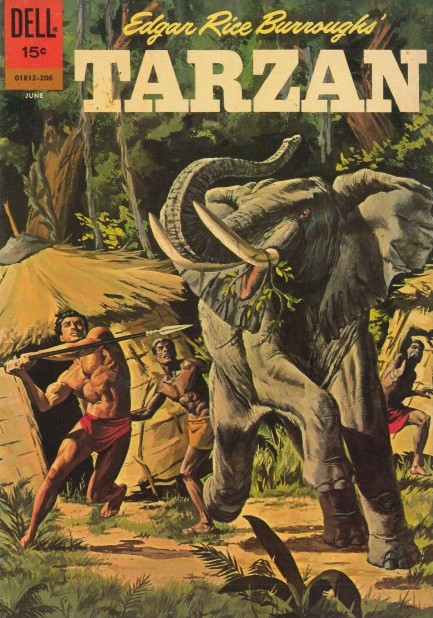

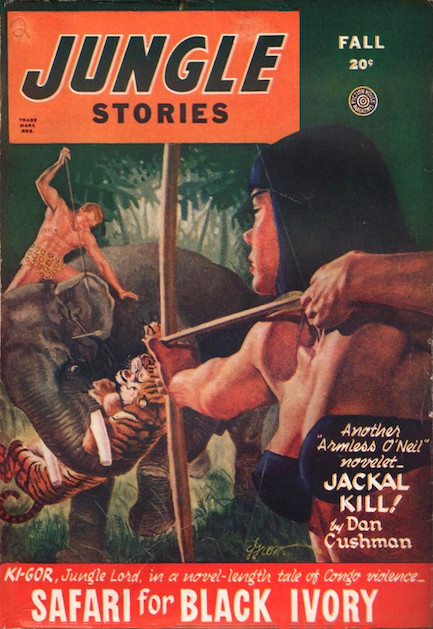

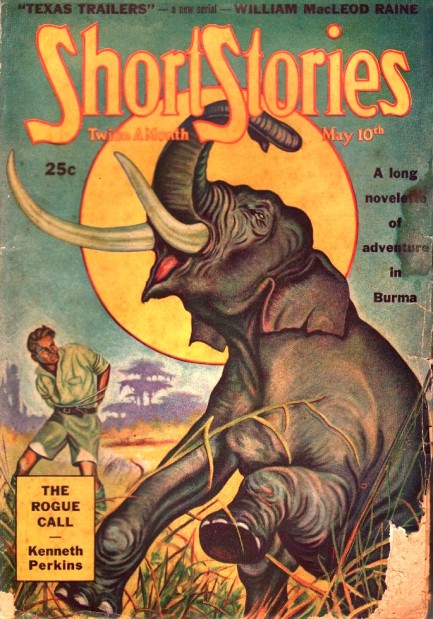

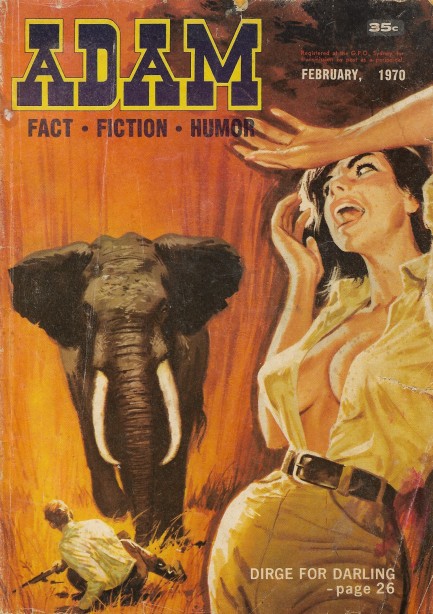

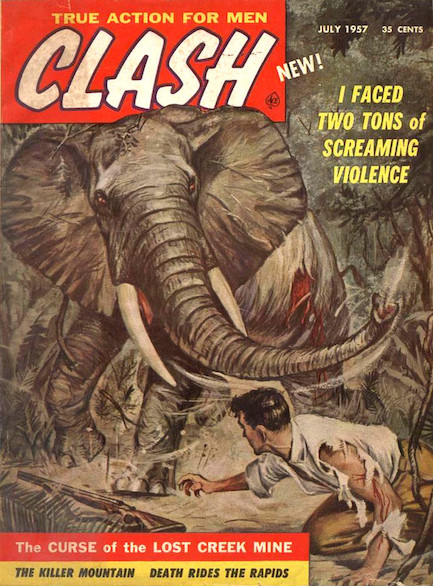

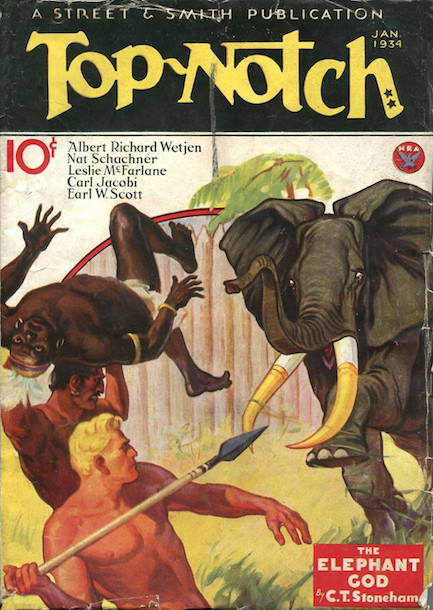

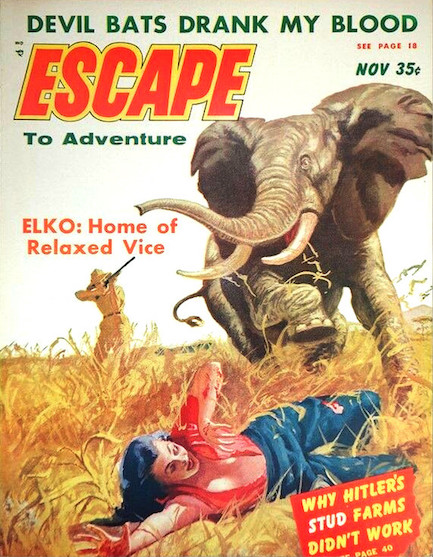

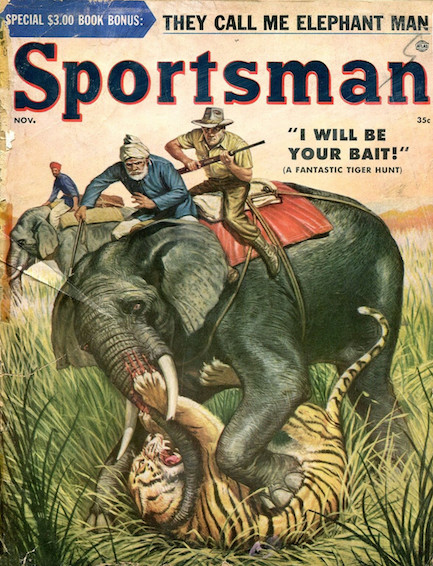

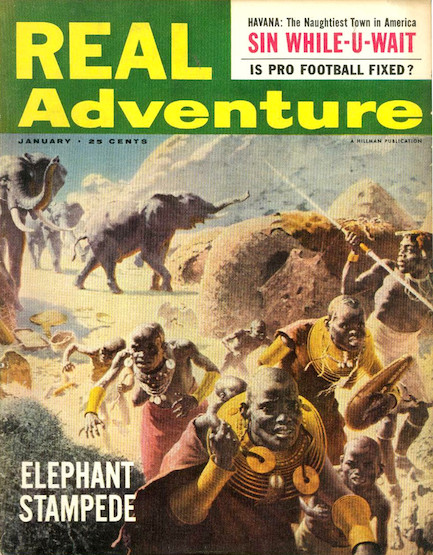

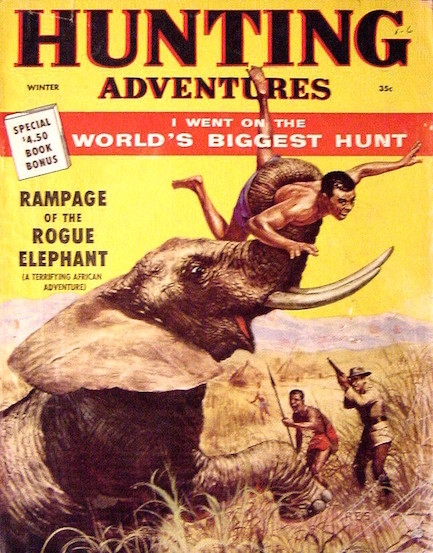

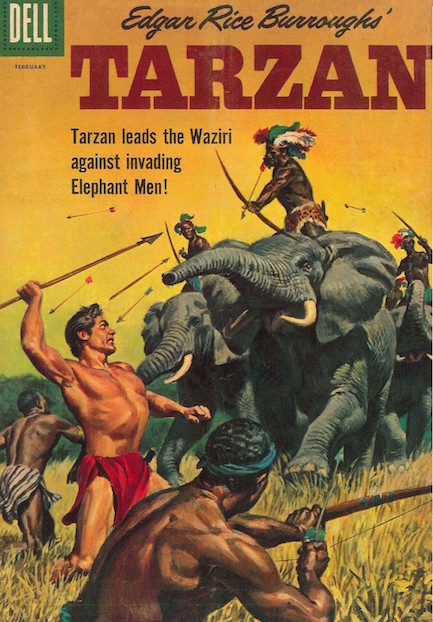

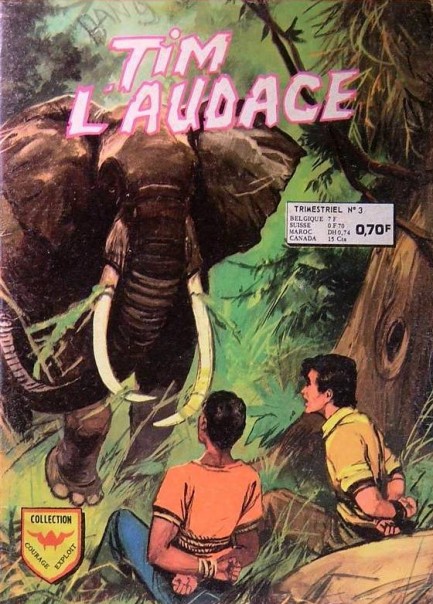

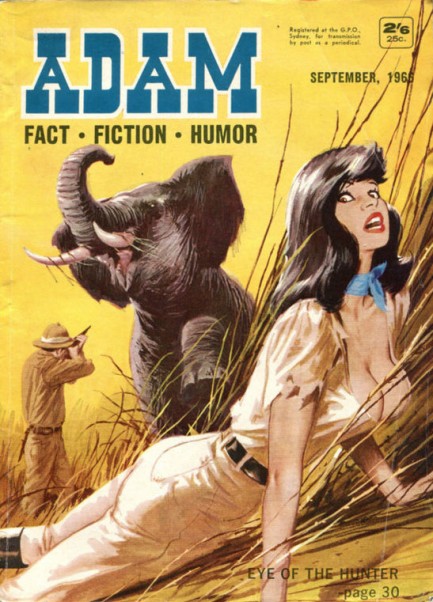

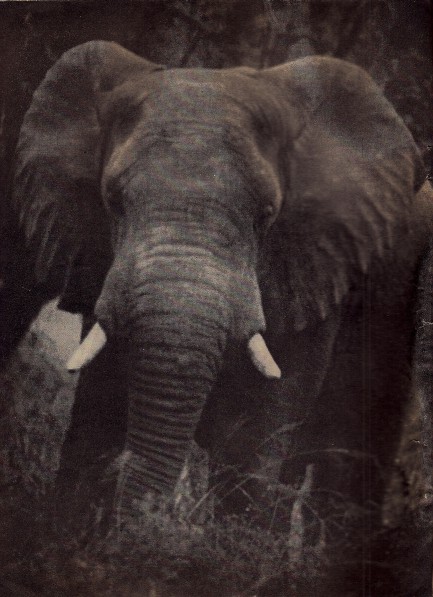

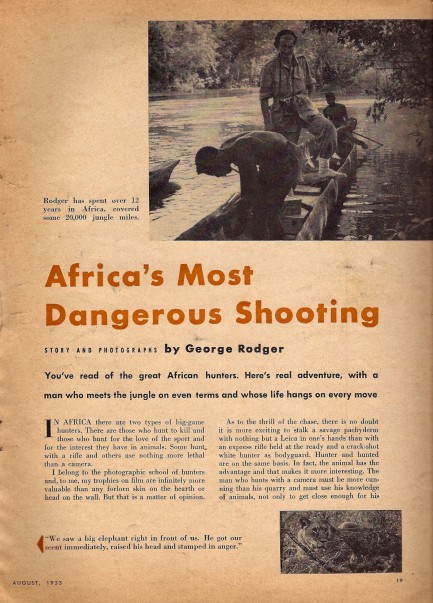

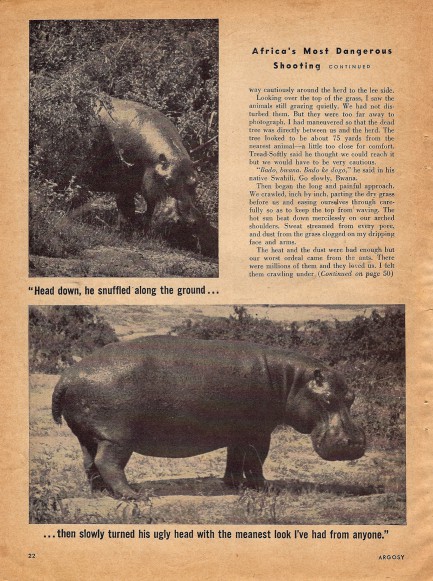

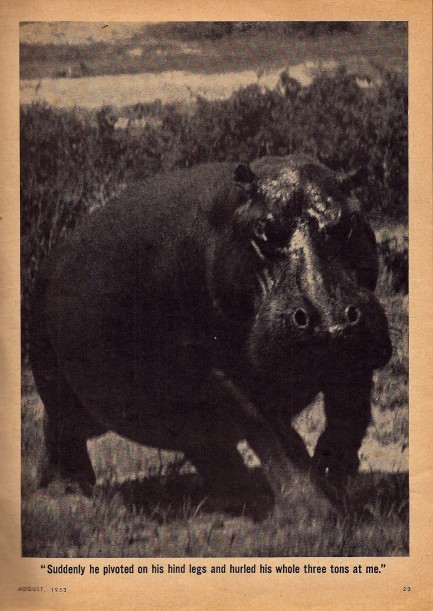

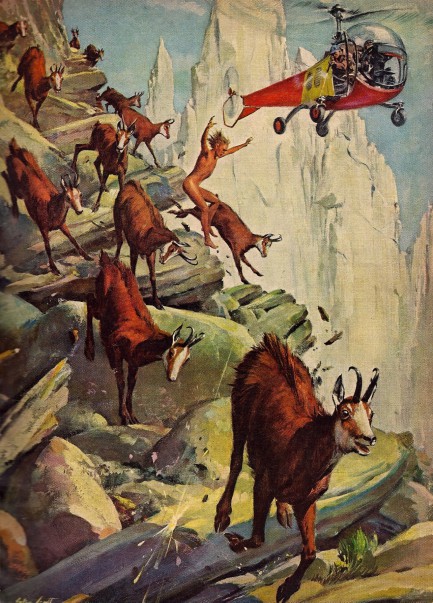

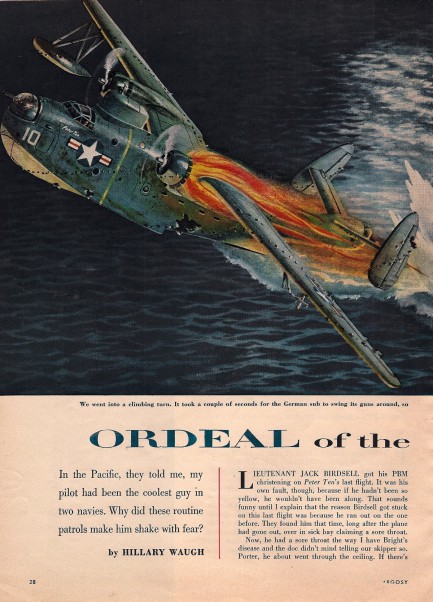

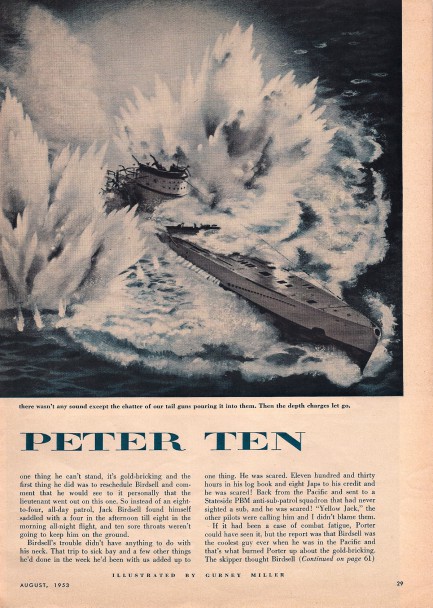

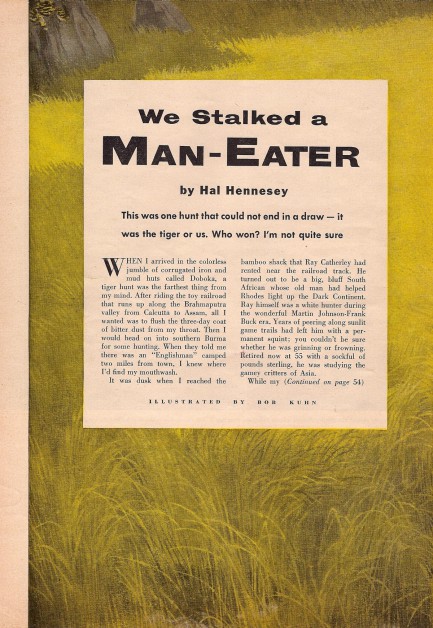

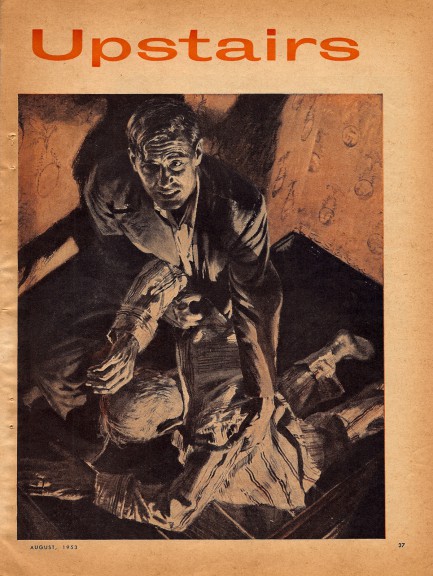

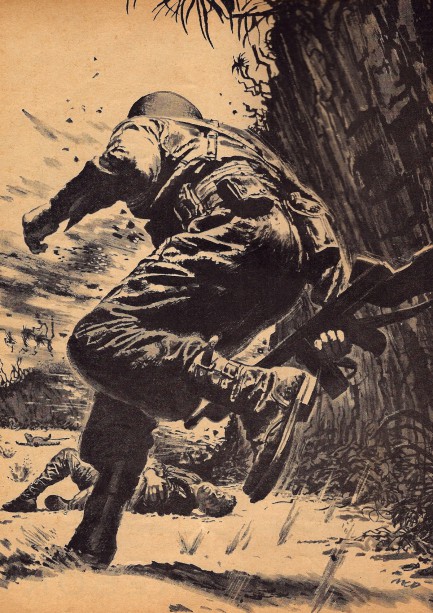

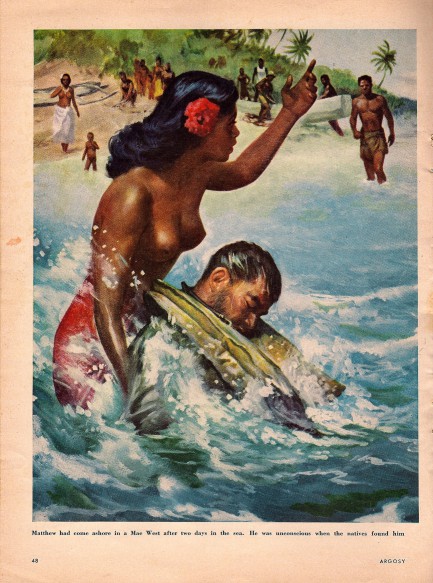

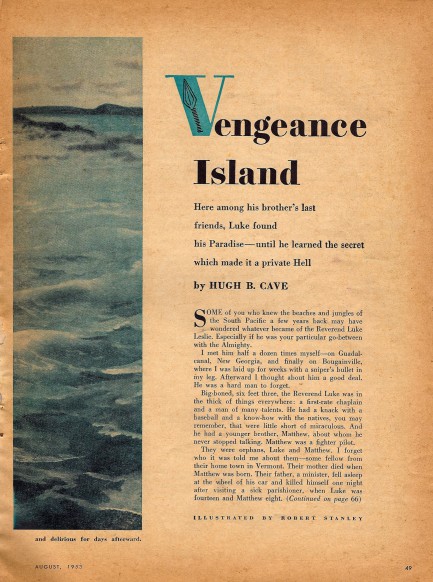

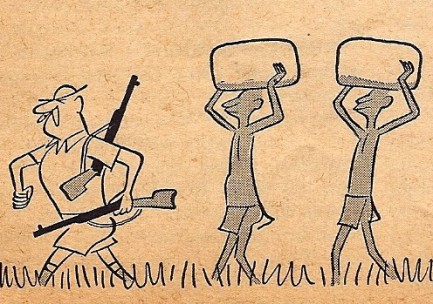

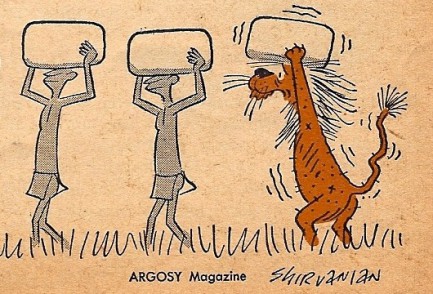

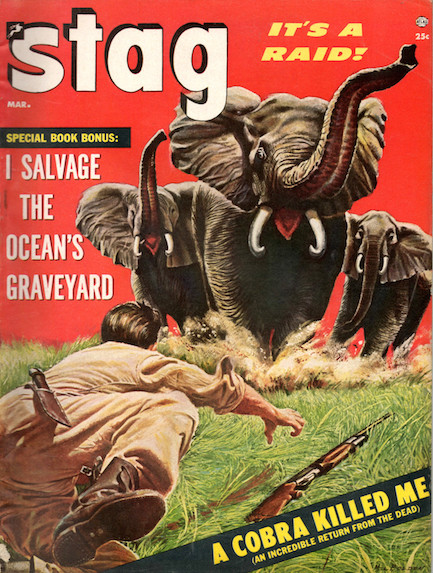

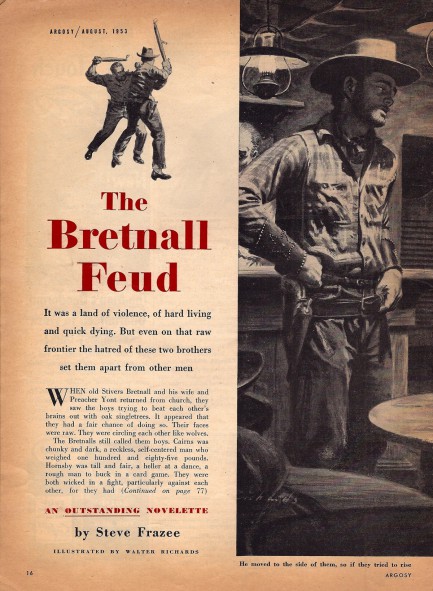

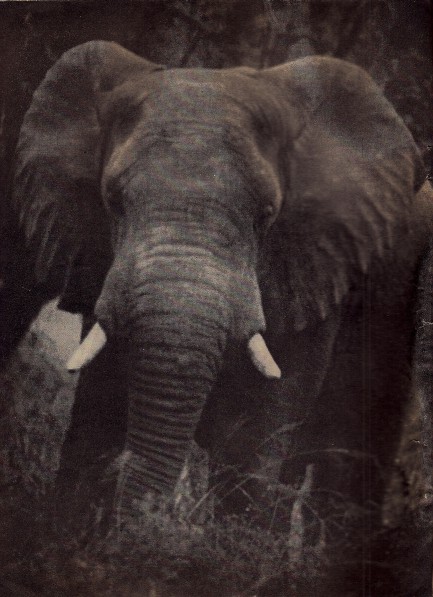

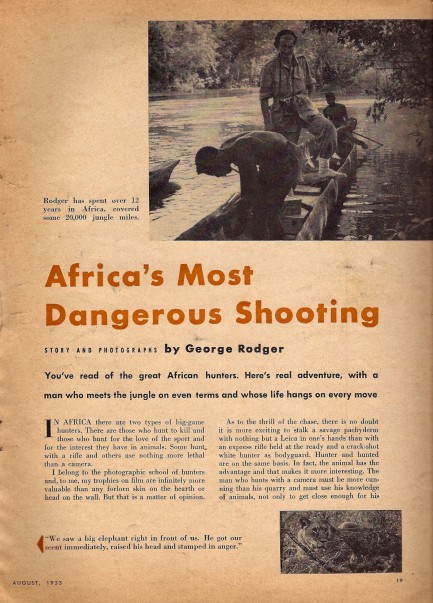

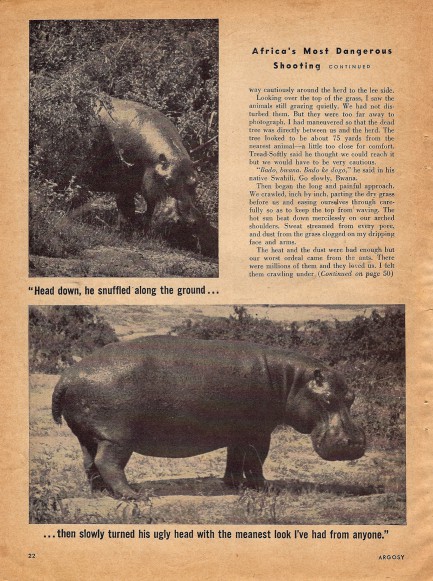

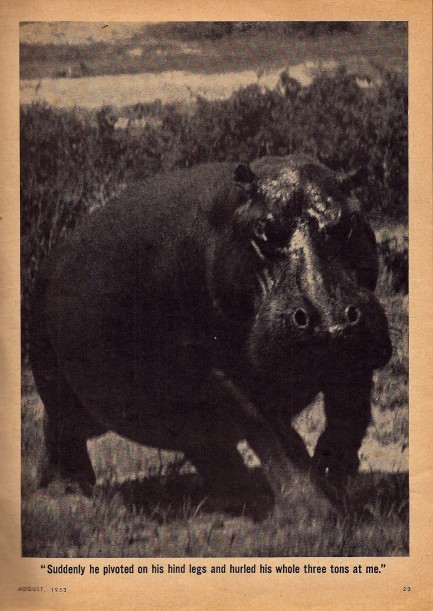

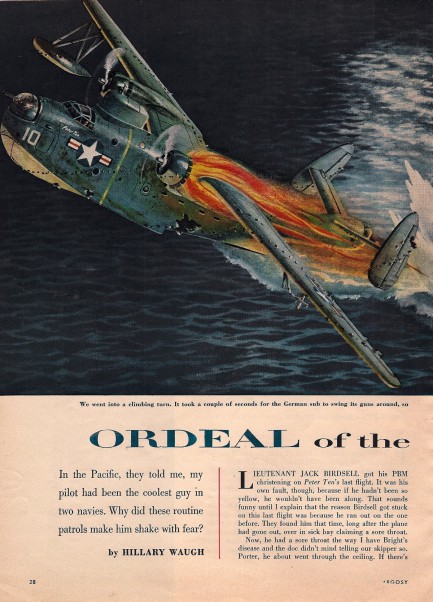

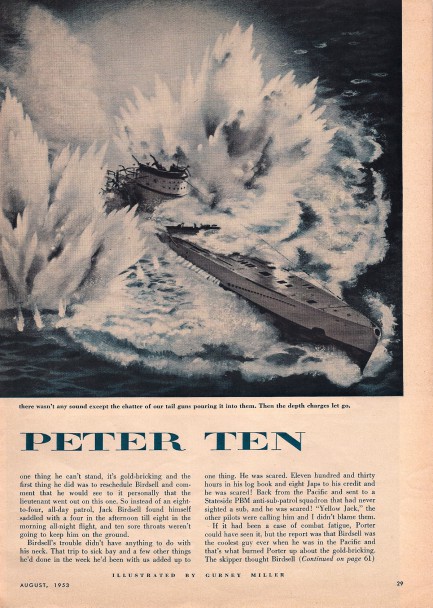

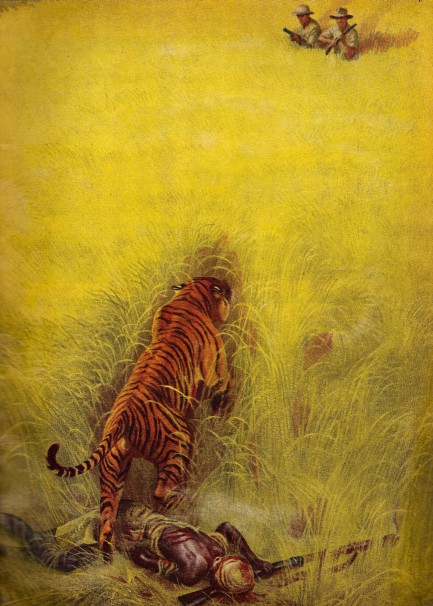

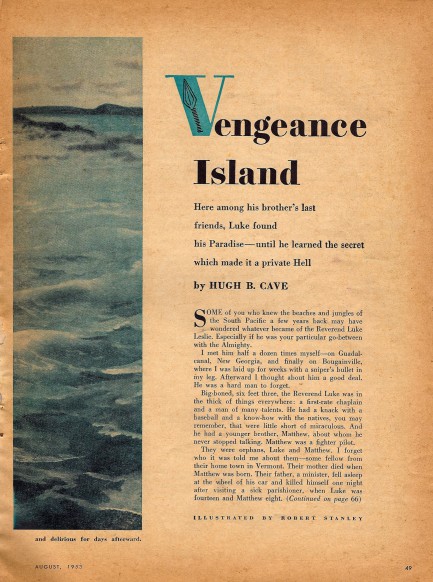

An argosy is a type of boat, and this 1953 Argosy—the self-billed “complete men’s magazine”—has a type of boat on the cover and a boatload of interesting features within. Much of them focus on hunting, which has been in the news Stateside of late due to several rich folks being outed for killing African animals. Argosy glorifies hunting in a way that was typical of the 1950s, when guys like Ernest Hemingway and John Huston mainstreamed knowledge of the practice. The presumption that man has a natural right to kill African animals for sport oozes from these Argosy stories. We made a game of inverting that presumption by mentally adding “because I was trying to shoot him” to the end of sentences. For instance, “He turned and hurled his entire three tons at me…” became, “He turned and hurled his entire three tons at me because I was trying to shoot him.” We liked the stories, though. They are exciting. But hey, times change—it ain’t The Snows of Kilimanjaro out there anymore. These big animals are way too important to be killing for sport. About fifteen years ago we took a road trip across the U.S. and came upon the Petrified Forest National Park. We expected to see countless mineralized trees, and we did see some, but the place is just a plain of scattered rocks. It didn’t used to be that way. A sign explained that millions of artifacts had been removed from the park over the years by tourists. Each one seemed meaningless to the person taking it, but over time the forest disappeared. Today we understand two important things we didn’t during the 1950s. First, humanity has no restraint when it comes to killing animals. There’s no point where the animal is too rare or valuable to be killed. The opposite, in fact—people simply pay more for the glory of doing it, and the number of interested parties is limitless. Second, a species reaches a level of scarcity where collapse is assured unless there are active and expensive human efforts made to prevent it. That collapse point comes long before every animal is killed, yet we don’t know exactly where it is for each species.

All of this means no large animal exists in true abundance. It doesn’t matter if a person shoots one of 50,000 of a species or one of the last 50. If a market exists for killing even one of them, the species is ultimately doomed, because stoppage is not structured into market systems—only higher pricing. There’s no doubt about this at all. The jury’s in. Anybody who doesn’t recognize it is lying to himself or herself. And extinction or near-extinction is too high a price for the ecology to pay in service to human ego. Scans below.

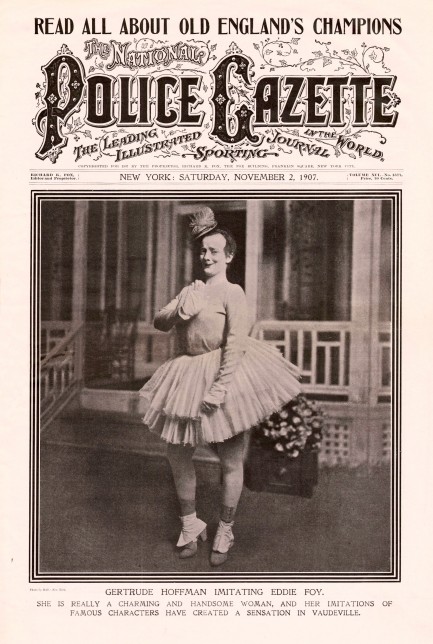

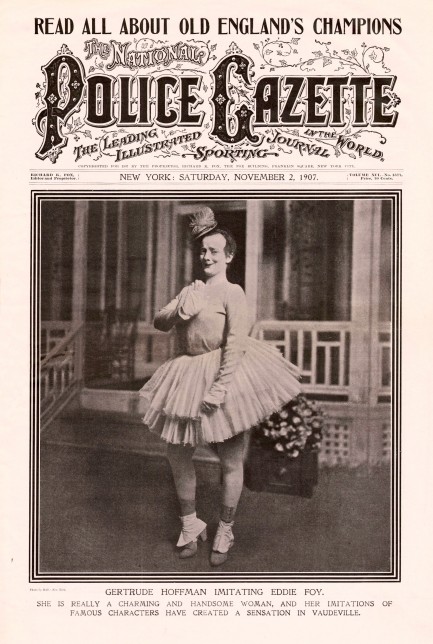

What do you get when a woman dresses as a man dressing as a woman? Meet the scary ballerina lady.

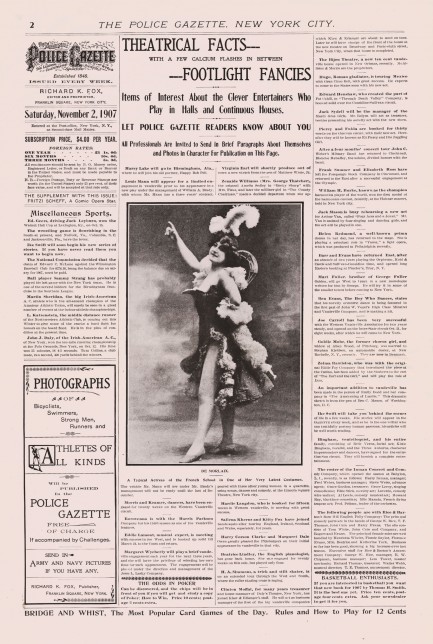

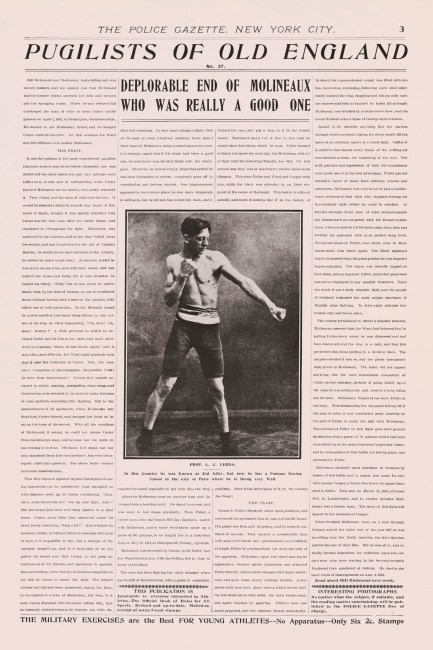

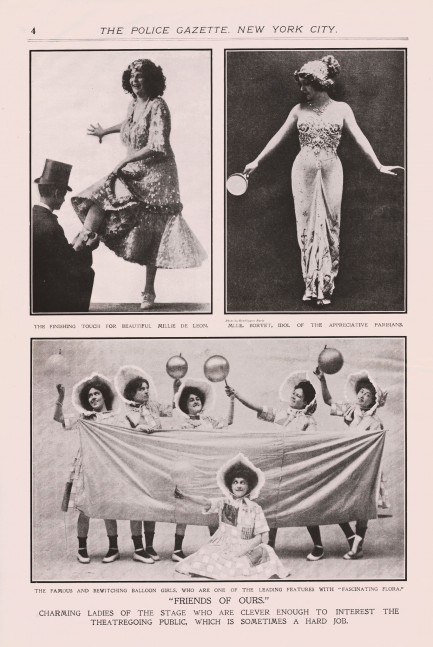

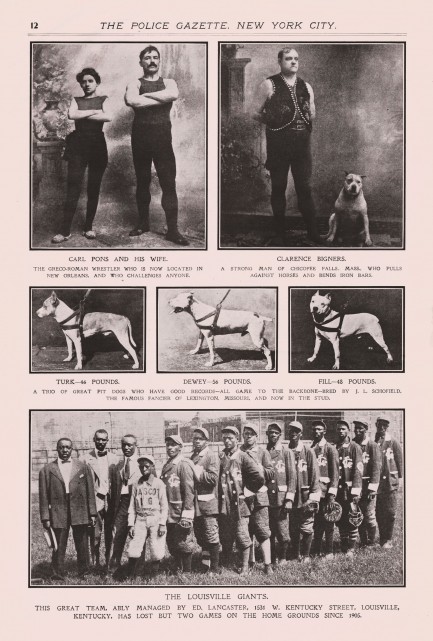

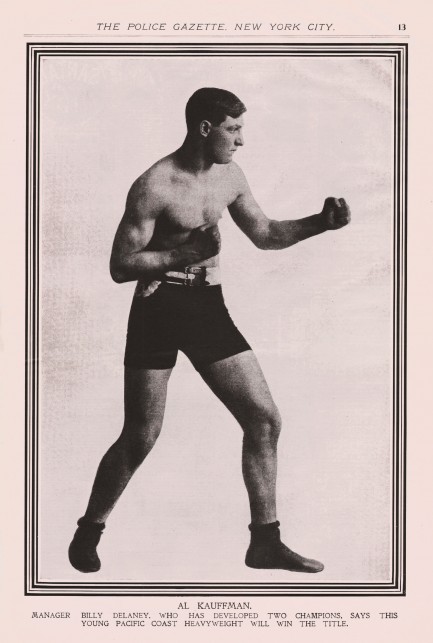

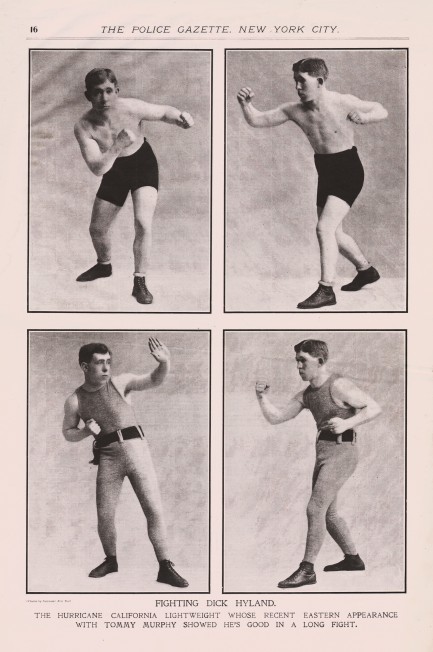

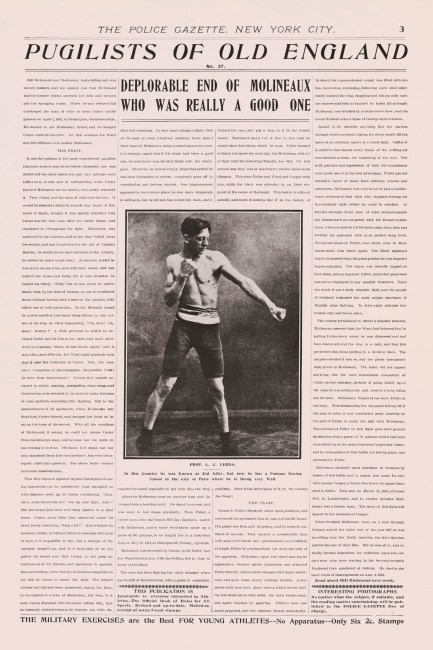

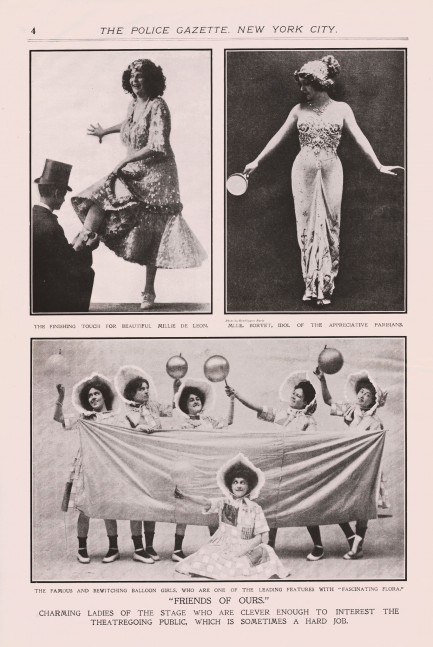

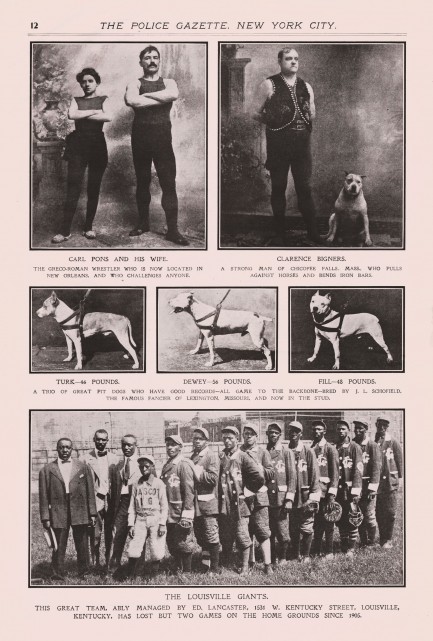

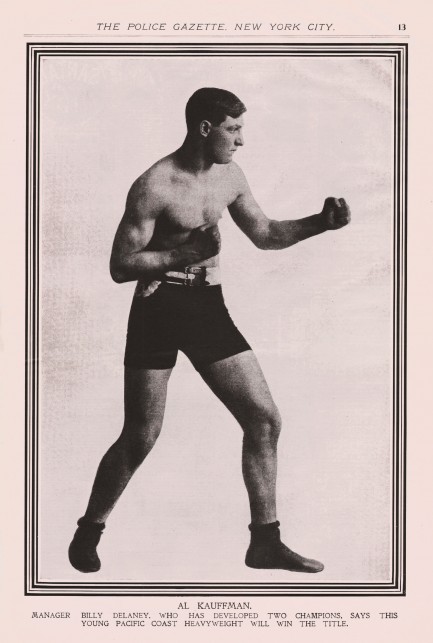

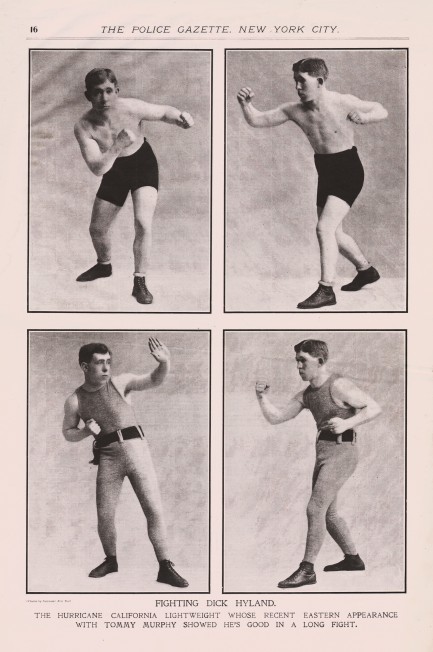

We’re reaching all the way back to 1907 for this issue of The National Police Gazette, making it the oldest one we’ve found. A 1907 publication may seem pre-pulp, but the pulp era is considered by many to have begun around 1896 with Frank Munsey’s all-fiction magazine The Argosy, which was distilled from his earlier The Golden Argosy. What struck us about this particular Gazette is the weird cover, on which you see famed vaudeville dancer Gertrude Hoffman imitating fellow vaudeville entertainer Eddie Foy, who we assume must have had a well known ballerina-in-drag routine. She looks positively frightening, at least to our eyes. But lest you think Hoffman’s cross-cross-dressing had to do with a physical resemblance to Foy, consider that she was also famous for her impersonations of female stars like Anna Held, Eva Tanguay, and Ethel Barrymore, and also regularly performed a Salome dance that landed her in jail more than once for lewd conduct. She simply had a chameleonic ability to convincingly imitate people of both sexes. Later she showed business acumen by forming and becoming director of her own dance troupe and touring the U.S. and Europe. We have a half dozen scans below, and more from the National Police Gazette and other tabloids than any other website. You can see all of it—just click here and scroll down.

At this point why bother leaving it on?

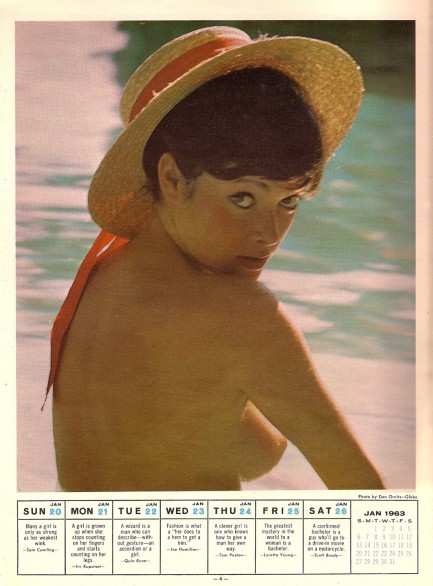

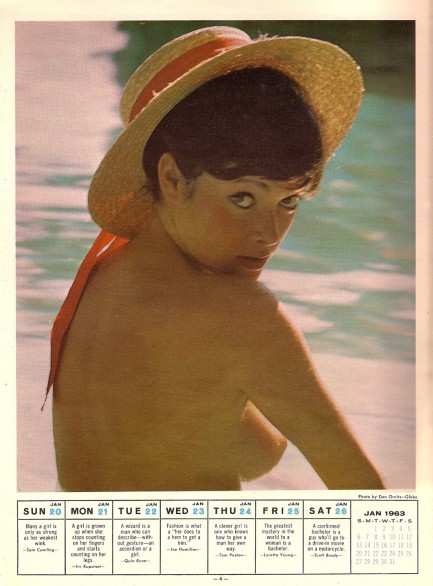

Here's the latest page from Goodtime Weekly with a shot from Don Ornitz of February 1958 Playboy centerfold Cheryl Kubert. Kubert is a bit of a mystery. Early Playboy centerfolds were pretty demure, and she showed less than normal. She had already appeared in magazines such as Pageant, Gala and Argosy, and after her Playboy appearance was featured in their 1959 calendar, but after that there’s only a bit appearance in the movie Pal Joey, and a bit part in 1980’s Smokey and the Judge. She died in 1989, supposedly from suicide. The calendar quips are below.

Jan 20: “Many a girl is only as strong as her weakest wink.”—Sam Cowling Jan 21: “A girl is grown up when she stops counting on her fingers and starts counting on her legs.”—Irv Kupcinet Jan 22: “A wizard is a man who can describe—without gesture—an accordion or a girl.”—Quin Ryan Jan 23: “Fashion is what a her does to a hem to get a him.”—Joe Hamilton Jan 24: “A clever girl is one who knows how to give a man her own way.”—Tom Poston Jan 25: “The greatest mystery in the world is a woman who is a bachelor.”—Loretta Young Jan 26: “A confirmed bachelor is a guy who’ll go to a drive-in on a motorcycle.”—Scott Brady

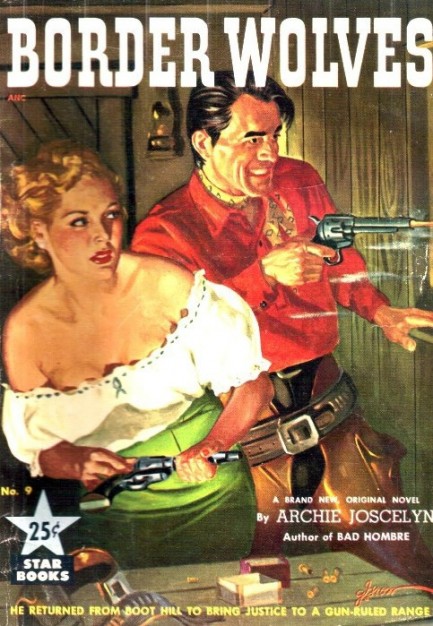

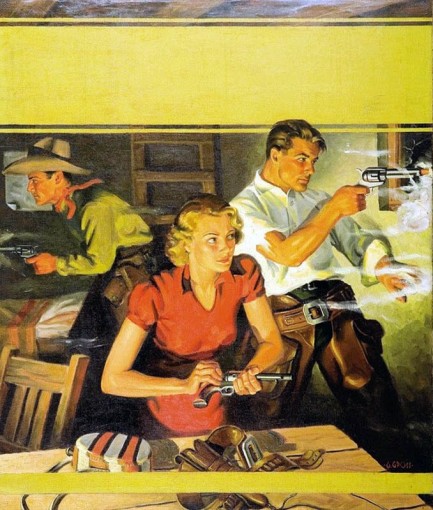

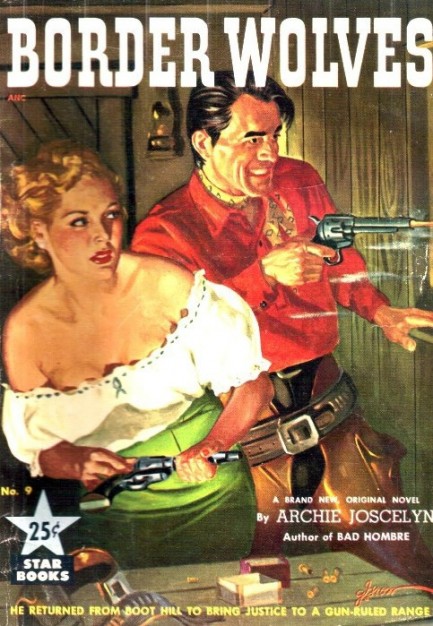

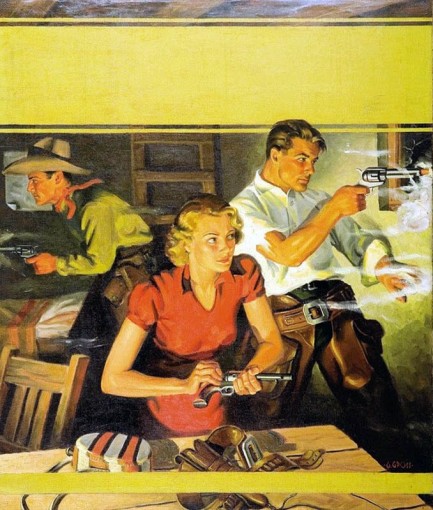

He may not be the best shooting gunman in the Old West, but you can’t fault his fashion sense.

This cover scan of Archie Joscelyn’s 1950 western Border Wolves was sent over from National Road Books, which is good timing, because the art is by George Gross and we featured one of his very best pieces back in October and said we’d get back to him. Gross (who should not be mixed up with German painter George Grosz) was a prolific artist who, as we mentioned in that previous post, was incredibly diverse, producing covers for Argosy, Baseball Stories, Bulls Eye Detective, Northwest Romances, Wings, Fight Stories, Saga, and many others. He was born in 1909 in Brooklyn, New York, began painting pulp covers in the 1930s and worked steadily through the 1980s, dying at the ripe age of ninety-four. You would suspect, looking at the shooting technique of the cowboy on the cover of Border Wolves, that Gross didn’t know much about guns. While that’s possible, we think the weird shooting position is a result of wanting to fit the cowboy’s entire arm on the cover. But he must have liked the result, because he used this awkward stance twice (see below). There are quite a few web archives of Gross art, so if you want to see more, let your fingers do the walking.

|

|

The headlines that mattered yesteryear.

2003—Hope Dies

Film legend Bob Hope dies of pneumonia two months after celebrating his 100th birthday. 1945—Churchill Given the Sack

In spite of admiring Winston Churchill as a great wartime leader, Britons elect

Clement Attlee the nation's new prime minister in a sweeping victory for the Labour Party over the Conservatives. 1952—Evita Peron Dies

Eva Duarte de Peron, aka Evita, wife of the president of the Argentine Republic, dies from cancer at age 33. Evita had brought the working classes into a position of political power never witnessed before, but was hated by the nation's powerful military class. She is lain to rest in Milan, Italy in a secret grave under a nun's name, but is eventually returned to Argentina for reburial beside her husband in 1974. 1943—Mussolini Calls It Quits

Italian dictator Benito Mussolini steps down as head of the armed forces and the government. It soon becomes clear that Il Duce did not relinquish power voluntarily, but was forced to resign after former Fascist colleagues turned against him. He is later installed by Germany as leader of the Italian Social Republic in the north of the country, but is killed by partisans in 1945.

|

|

|

It's easy. We have an uploader that makes it a snap. Use it to submit your art, text, header, and subhead. Your post can be funny, serious, or anything in between, as long as it's vintage pulp. You'll get a byline and experience the fleeting pride of free authorship. We'll edit your post for typos, but the rest is up to you. Click here to give us your best shot.

|

|