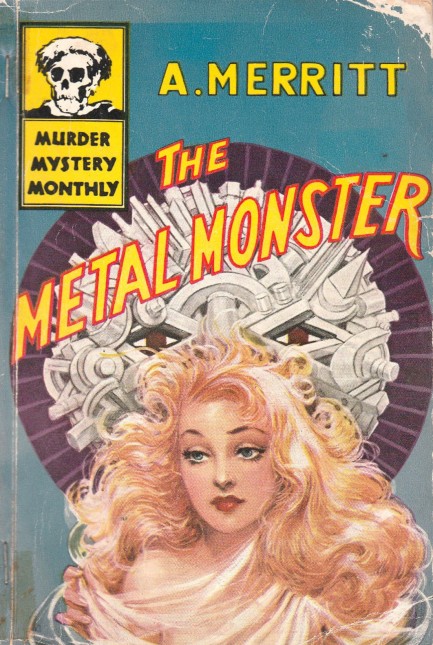

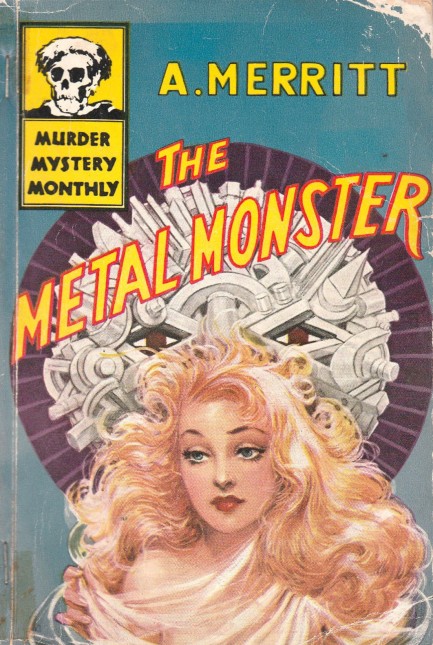

The Metal Monster is science fiction as a mind-altering trip.

We usually read novels from the ’40s, ’50s, and ’60s, but we took a trip to the heart of the pulp era with Abraham Merritt's The Metal Monster, which made its first appearance as a serial in Argosy All-Story Weekly in 1920. The above paperback came in 1946 from Avon Publications' Murder Mystery Monthly #41, and has cover art by the always interesting Paul Stahr, who worked extensively with Avon during this period. You can click his keywords at bottom and see all four of the covers by him we have in the website. There are also interesting covers by other artists on later editions of The Metal Monster. We'll try to show you a couple of those later.

In Merritt's tale, four explorers travel into an uncharted Himalayan valley and subsequently are trapped by what lives in the area—Persian soldiers seemingly stuck in time, or whose traditions have gone unchanged for two thousand years. There's something else in the valley too—a shimmering goddess creature named Norhala and her metal swarm, which is usually a blizzard of small geometrical shapes, but can collect into forms as needed, for example a towering monster with six whiplike arms that scythe through the ranks of the Persians, ripping them to shreds. While Norhala has some control over the swarm, we later learn that the creatures came from the stars, feed on sunlight, and eventually eradicate biological life on every planet they colonize. So that's not good.

Merritt's prose brings to mind H.P. Lovecraft, because he similarly tasks himself with describing the indescribable. Lovecraft fans know what that means—the creatures in his mythos are so mindbending as to drive humans insane merely to gaze upon them. Lovecraft challenged himself to describe those beings, and much of the horror in his writing derives from those attempts. But he sometimes took his built-in escape hatch too, ultimately saying the creatures simply were so inhuman they couldn't be described. Merritt faces the same challenge, and in his descriptions usually manages to be vivid yet vague:

Where the azure globe had been, flashed out a disk of flaming splendors, the very secret soul of flowered flame! And simultaneously the pyramids leaped up and out behind it—two gigantic, four rayed stars blazing with cold blue fires. The green auroral curtainings flared out, ran with streaming radiance—as though some spirt of jewels had broken bonds of enchantment and burst forth jubilant, flooding the shaft with its freed glories.

The tale is filled with psychedelia like the example above, though it does get more concrete in parts, like here:

[They] lifted themselves in a thousand incredible shapes, shapes squared and globed and spiked and shifting swiftly into other thousands as incredible. I saw a mass of them draw themselves up into the likeness of a tent skyscraper high; hang so for an instant, then writhe into a monstrous chimera of a dozen towering legs that strode away like a gigantic headless and bodiless tarantula in steps two hundred feet long. I watched mile-long lines of them shape and reshape into circles, into interlaced lozenges and pentagons—then lift in great columns and shoot through the air in unimaginable barrage.

Honestly, all these hyper-detailed descriptions get tedious at times, as does the pervasive incredulity of Merritt's narrator Dr. Walter T. Goodwin. We get that he's dumbfounded, but the human mind has an amazing capacity to normalize that which it sees constantly, therefore we'd prefer if Goodwin weren't repeatedly floored by everything he encounters. That way, when he finally learns what form the metal swarm actually takes—that of a vast city—we readers can finally be truly amazed. However, when we think of The Metal Monster as an Argosy serial circa 1920, it's visionary, and we imagine it must have been intensely gripping. Merritt may merit more exploration.

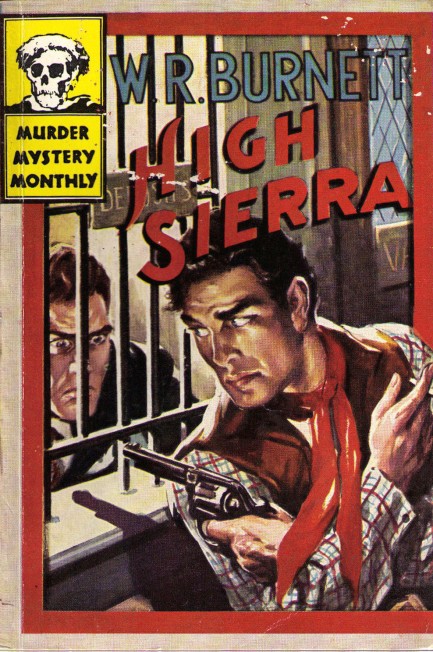

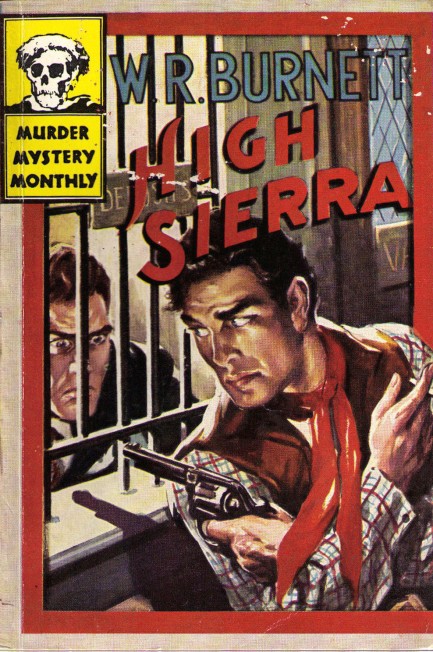

Yep, this is a robbery. Faked you out, right? Now pretend I'm asking for a back rub and empty the cash drawer.

Above, a great cover for W.R. Burnett's High Sierra from Avon Publications' series Murder Mystery Monthly, 1946, featuring a very slick robber painted by Paul Stahr. We shared another cover for this book you can see here.

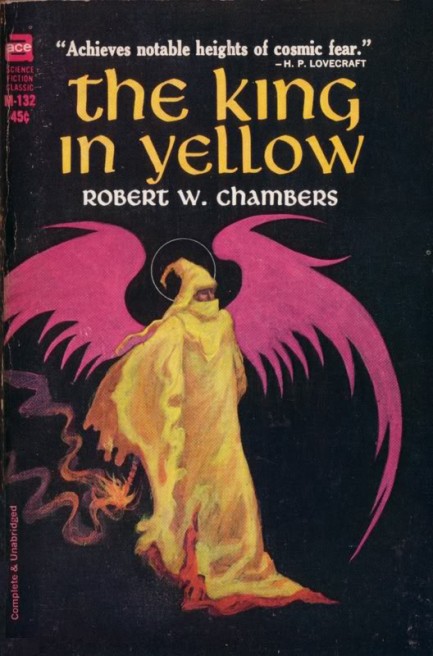

Long live the King—in Yellow, that is.

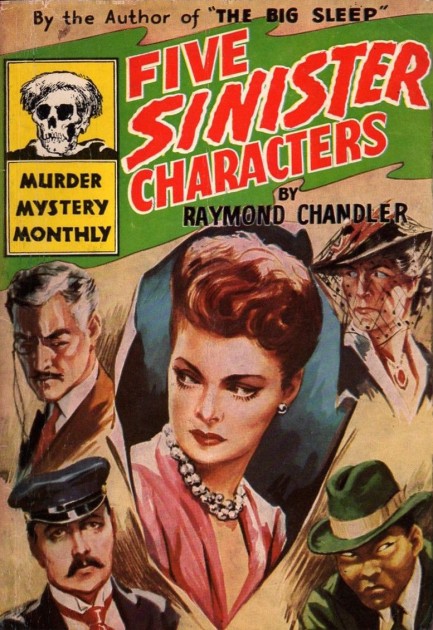

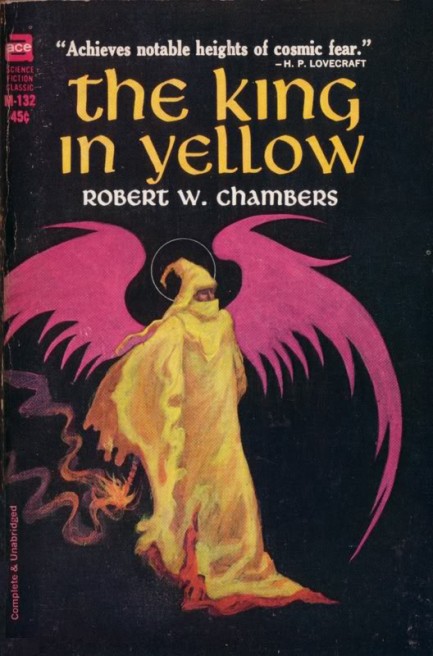

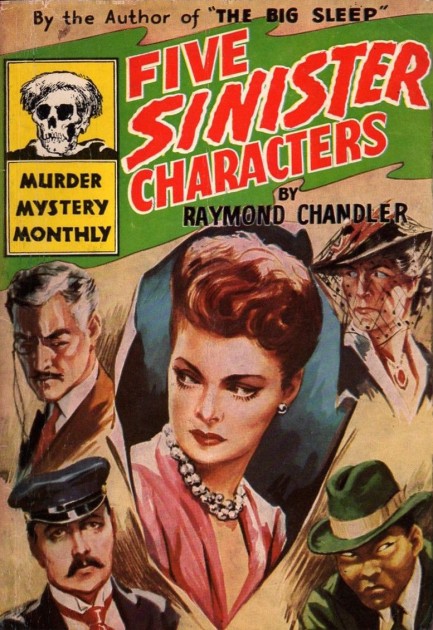

The interesting cover above for Five Sinister Characters was painted by Paul Stahr and fronts a Raymond Chandler short story collection that appeared as an edition of Avon Publications' Murder Mystery Monthly series in 1945. The book is composed of Chandler's "Trouble Is My Business,” “Pearls Are a Nuisance,” “I'll Be Waiting,” “The Red Wind,” and “The King in Yellow.” H.P. Lovecraft fans probably know that last title. The King in Yellow is an avatar of one of Lovecraft's terrible gods Hastur, aka The Unspeakable One. Lovecraft in turn lifted it from Robert W. Chambers' 1895 collection of weird stories The King in Yellow, which you see below.

However, Chandler's “The King in Yellow” is unrelated to Lovecraft and Chambers. Chandler's tale is a detective yarn, while Chambers' collection is, well, very weird, and within that weirdness The King in Yellow is a fictional play that drives those who it read it insane, or at least deeply despondent. Midway through Chandler's story a character says, “'The King in Yellow.' I read a book with that title once.” A clear nod to Chambers' work.

who it read it insane, or at least deeply despondent. Midway through Chandler's story a character says, “'The King in Yellow.' I read a book with that title once.” A clear nod to Chambers' work.

But as we said, Chandler's “The King in Yellow” is a crime story. It follows hotel detective Steve Grayce, who evicts jazz trumpetist and lover of yellow clothing King Leopardi for unruly late night conduct. The King later ends up shot to death in a woman's bedroom across town, and Grayce—fired for tossing a famous client—tries to figure out why the murder happened, and to get the woman off the hook in whose bed the King bled out. It's an excellent story, as are the others. But you already know that. It's Chandler.

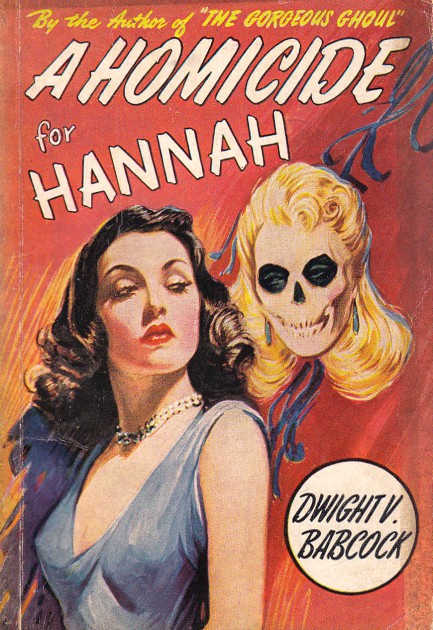

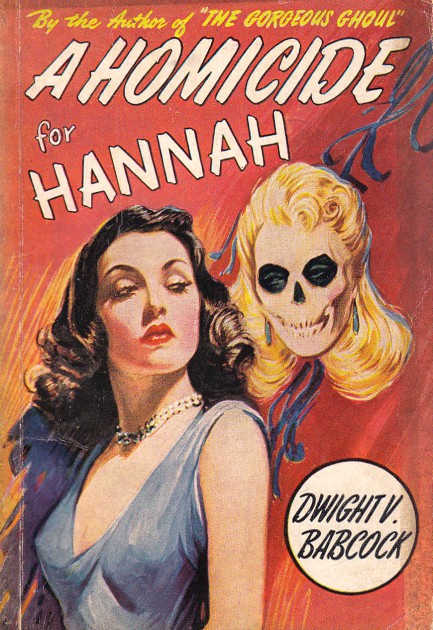

Just give me a second to put my face on.

Interesting cover work from early pulp illustrator Paul Stahr for Dwight V. Babcock’s mystery A Homicide for Hannah. The art is supposed to be suggestive of Hannah Van Doren’s dual nature—she looks like an innocent sweetheart on the outside, but inside has a morbid fascination with murder and mayhem. Her darker half serves her well as she prowls Hollywood’s grimy corners writing for True Crime Cases. First of a trilogy, the hardback appeared in 1941, and the Avon paperback above is from 1945.

who it read it insane, or at least deeply despondent. Midway through Chandler's story a character says, “'The King in Yellow.' I read a book with that title once.” A clear nod to Chambers' work.

who it read it insane, or at least deeply despondent. Midway through Chandler's story a character says, “'The King in Yellow.' I read a book with that title once.” A clear nod to Chambers' work.