Look at that view, men! Just think how much money a trip like this would cost us if we were civilians!

Donald Downes' World War II combat and espionage novel The Scarlet Thread originally appeared in 1953, with this Panther Book edition coming in 1959, adorned with cover art from an unknown. Like many mid-century war novelists, Downes saw it all firsthand. He was in the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI), the British Security Coordination (BSC), and the OSS (we don't need to decipher that one, right?), and saw action against the fascists in Italy and Egypt. This novel, his first, draws on those experiences in telling the story of an aviator sent on a mission to eliminate a suspected double agent. Its French translation won Downes the 1959 Grand Prix de Littérature policière. Mission accomplished.

Looks like we're dead meat. You know what I want my gravestone to say? “Just like always it was my stupid brother's fault.”

Author Max Brand, née Frederick Faust, was incredibly prolific for a guy who died early. He produced numerous stories and around a hundred fifty novels, including the source material for film and television's Dr. Kildare, and the 1956 western Brothers on the Trail, which you see here with Robert Stanley cover art. Brand was killed in 1944 at age fifty-one while working as a war correspondent in Italy, but he left quite a literary legacy.

Always aim as high as you can.

Dolores del Río poses with a machine gun during a 1943 Mexico City photo session meant to drum up support for the country's participation in World War II. Women from the civilian organization Servicio Femenino de Defensa were photographed by Hoy magazine, and del Río, one of the membership, took part. There was a caption in the magazine about her giving up her Hollywood finery to become a “dangerous modern soldier,” but she didn't participate in the war except as a symbol and fundraiser, as far as we know.

Gonna wait till the midnight hour, when there's no one else around.

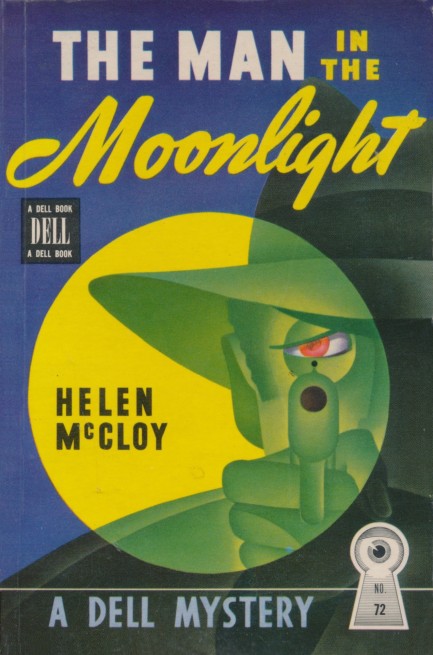

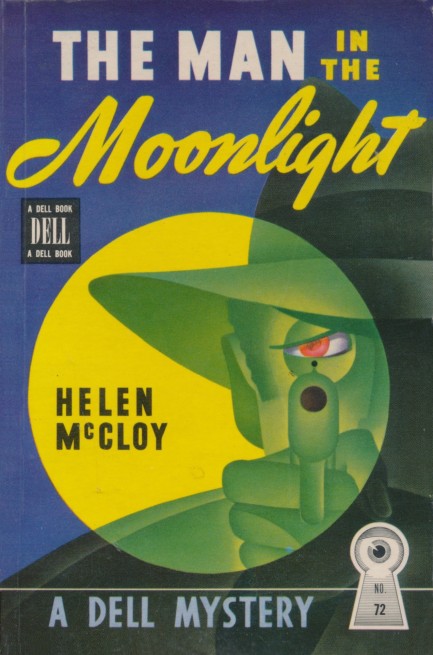

Above you see a cover effort by Gerald Gregg for Helen McCloy's 1945 mystery The Man in the Moonlight. This is from Dell Publications, and you probably recognized it right away as a mapback edition. You see that here too, with its fictive university campus. Above you see a cover effort by Gerald Gregg for Helen McCloy's 1945 mystery The Man in the Moonlight. This is from Dell Publications, and you probably recognized it right away as a mapback edition. You see that here too, with its fictive university campus.

The story is a variation of a locked room mystery, however it requires more than the usual helping of suspension of disbelief from readers. Basically, a university psychologist stages an experiment that's, more than anything, a form of live action role playing in which a colleague is to attempt to achieve the circumstances needed to commit a murder. But the psychologist is really testing more than his willing maze rat suspects, which is why in the midst of the experiment the parameters suddenly change in a way designed to induce panic. We won't get into the ethics of that.

It's during this emotional experiment that the murder occurs, and it just happens that police detective Patrick Foyle is on campus when it happens. He's on the case in seconds, but much of the investigation (and narrative) falls to a psychiatrist named Basil Willing. Between cop and headshrinker the culprit will out, as they always do. We didn't really buy any of it, but we did like the fact that the story was set in 1940 and brought in the specter of Nazi involvement. Here's a fun line: Even in the infinitely remote world of the molecule [no-spoiler] ran afoul of Nazi policy. It's always been true—fascists get their noses deep into everything.

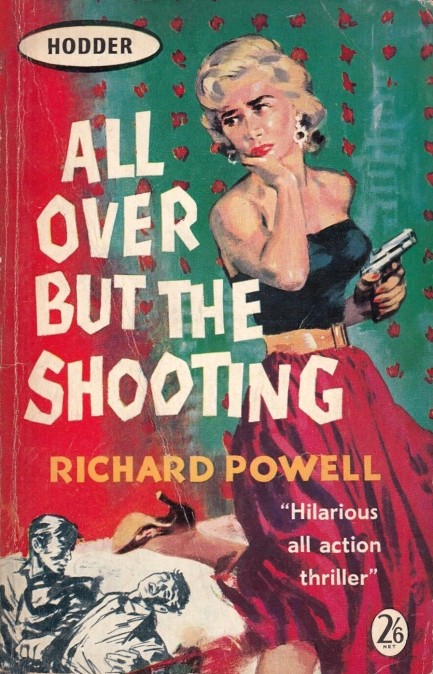

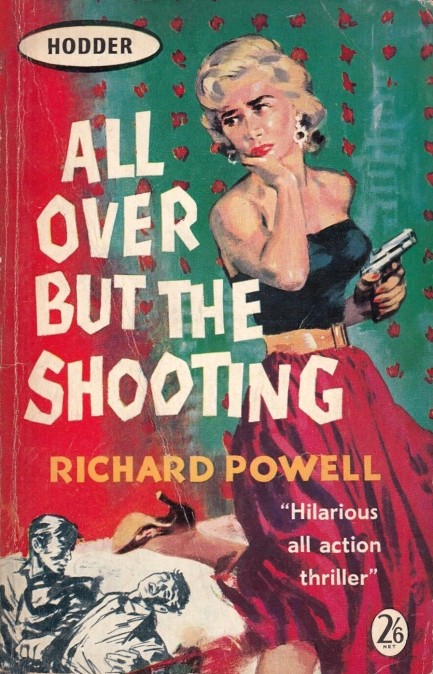

Powell shoots for a comedic mystery but doesn't have Hammett's perfect aim.

What is a "hilarious all-action thriller" like? That's the question that went through our minds when we impulsively ordered Richard Powell's 1946 novel All Over but the Shooting, though we were also drawn by the cover. The book was originally published by Popular Library, but the striking version you see above with art that's unfortunately uncredited came from the British imprint Hodder & Stoughton in 1952. Powell weaves a tale set in 1942 about Richard Blake and his danger-magnet wife Arabella—Arab for short—who believes she's stumbled across a spy plot centered around a Washington, D.C. women's boarding house. Determined to delve for answers—and to her husband's chagrin—she pretends to be a single woman, takes a room, and starts poking around. Her suspicions are of course correct. The place is a den of Nazis.

Powell thinks outside the box about every aspect of his story: how the conspiracy is uncovered, how the investigation proceeds, what clues are found, and what leaps of intuition keep the intrepid Arabella moving toward a solution. But the entire story is preposterous. Example: when Arab seems likely to be connected to a raincoat she lost while fleeing for her life, her hubby manages to sneak into the room where it's being kept—while its occupant is just upstairs—and have it altered in five minutes by a conveniently situated maid. That way the coat won't fit Arab when the villain tries to say it's hers.

That and about two dozen other moments are silly. Powell achieved, we think, exactly what he set out to do as an author, but we didn't find the book to be exactly scintillating. It was no Thin Man, for example, Dashiell Hammett's smashingly successful amalgam of humor and danger. But in the same way Arab erodes her husband's disbelief and finally gets him to buy into her wacky ideas, she wore us down too. She's a fun character, and makes the book worth a read. We won't seek out Powell again, but one spin around wartime D.C.? Sure, okay.

Toto we’re not in Africa anymore.

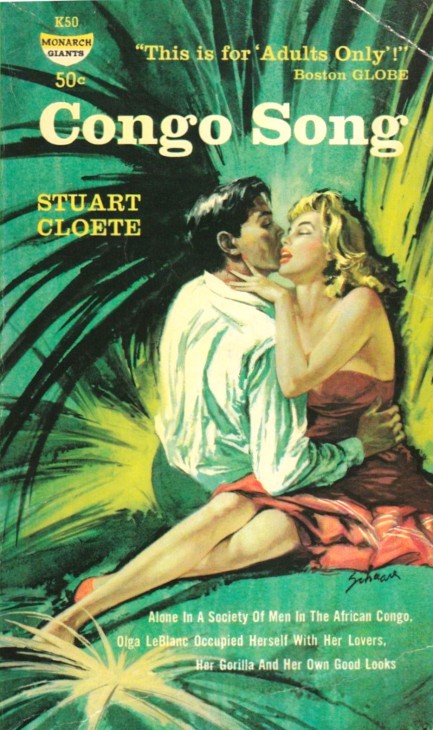

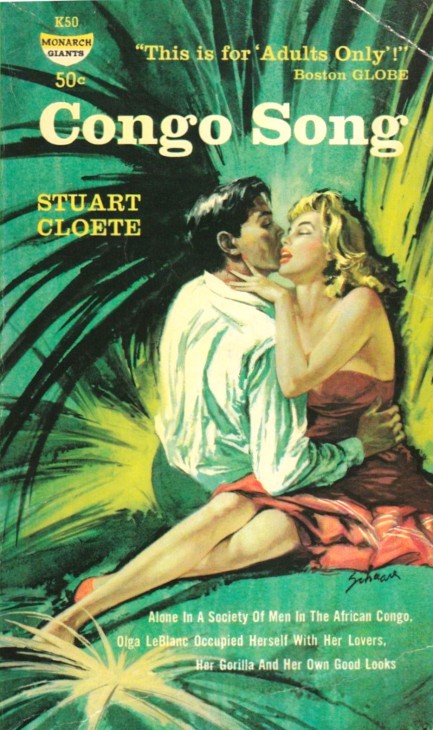

We said we'd get back to Stuart Cloete’s 1943 jungle drama Congo Song, and here we are. The book has been reprinted often, including in the 1958 Monarch edition you see above, with Harry Schaare cover art. Its popularity certainly owed something to the fact that it was another book that nurtured popular Western stereotypes about life in Africa, including that it attracted decadent and damaged whites whose weaknesses were inevitably amplified by the deep, dark, primitive, savage, mysterious continent. You've read something like this once or twice, we bet, thanks to Hemingway and others, though Cloete, who was from South Africa, writes in an entirely different style than Papa:

This was the Congo song: the song of sluggish rivers, of the mountains, the forests; the song of the distant, throbbing drums, of the ripe fruits falling, of the mosquitoes humming in the scented dusk; the song of Entobo, of the gorilla, and the snake. The song no white man would ever sing. The wild dogs cry out in the night as they grow restless, longing for some solitary company. Oops—that last sentence is from the Toto song “Africa.” Don't know how that slipped in there. Anyway, Congo Song unfolds in the months before the start of World War II. Cloete’s characters are diverse, with his main creation being Olga le Blanc, the only woman living in an isolated outpost called Botanical Station with several men, including her husband, a researcher who spends a lot of time away. Olga is a vamp who must make other men fall in with love her, and her affections don't end at homo sapiens sapiens—she has a gorilla, unsubtly named Congo, that she nursed at her own breast when it was an infant. Cloete’s symbolism is pretty thick milk. Erudite conversation, circular philosophizing, seductions, and secrets abound at Botanical Station. One of the other main characters is an American named Henry Wilson who has been sent by handlers in Nairobi to keep an eye on the doings of a German spy named Fritz von Brandt. Olga, meanwhile, spies on von Brandt for the English—sometimes from his bed. Other characters have less purpose, and many eccentricities. One drinks too much. Another sleeps with teenaged Congolese girls under the guise of employing them as domestics. The researcher seems to love trees more than Olga. Nobody is particularly happy. Who is who? Who wants what? There's another spy, who we won't name, a machine-like man, asexual, immune even to Olga: Women were the weakness of so many. Money, luxury, power, all resolved themselves finally into women. That was where the money went. That was what the power was used to obtain. How lucky he was to have been born without sexual feelings. All the duplicity in Congo Song derives from the looming war in Europe, but there's also another driver: “Under all this,” Olga observes, “is the never-ending fight for the riches of Africa.”

Despite all the dinners, safaris, subterfuges, and soliloquies—or maybe because of the soliloquies—the book doesn't gather momentum until about page two-fifty, after a fatal accident. Then things move fast enough to cause whiplash. Death comes by various methods, none of them banal. And of course there's still that gorilla. He lives in the house with the le Blancs, but Olga lets him loose regularly. Surely that'll end with limbs separated from bodies and blood on the louvered doors. And Cloete clearly must—absolutely must—squeeze in a little lethal witch-doctoring. No more plot hints. However, it isn't a spoiler to reveal that since Cloete follows the basic blueprint of other books of this type, at least a character or two eventually flee for modern civilization. But they'll remember Congo with bittersweet nostalgia—primarily during a maudlin denouement drawn out over several chapters. But it's understandable—it's not easy to let go of such beauty and horror. Not easy to let go of Congo Song either. It wasn't perfect, but it was very interesting. It’s gonna take a lot to take me awaaaay from yoooou… There’s nothing that a hundred men or moooore could ever doooo… I bless the rains down in Aaaafricaaa…

It's not comfortable, but it's reliable.

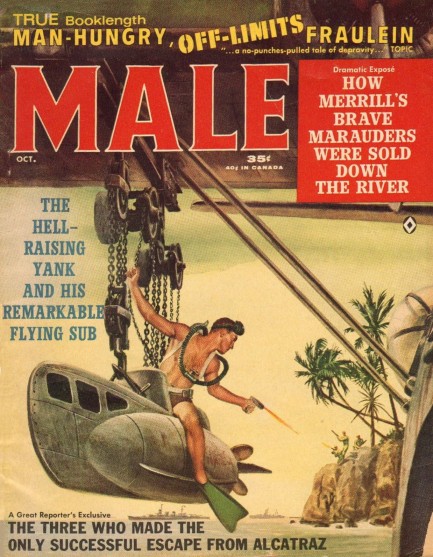

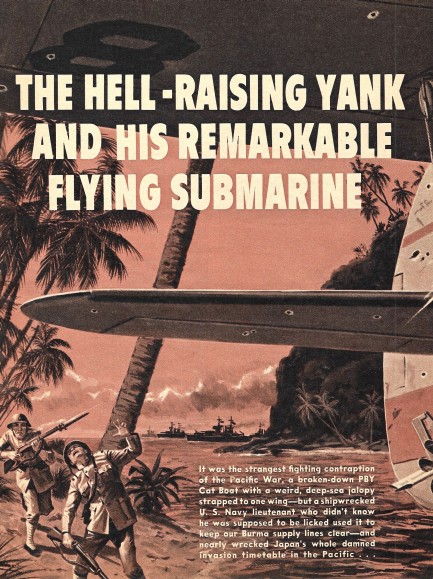

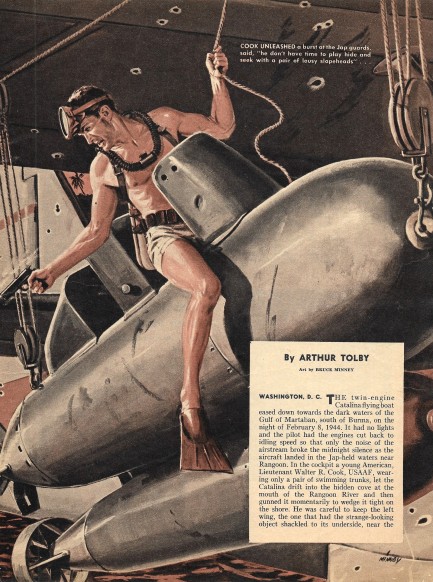

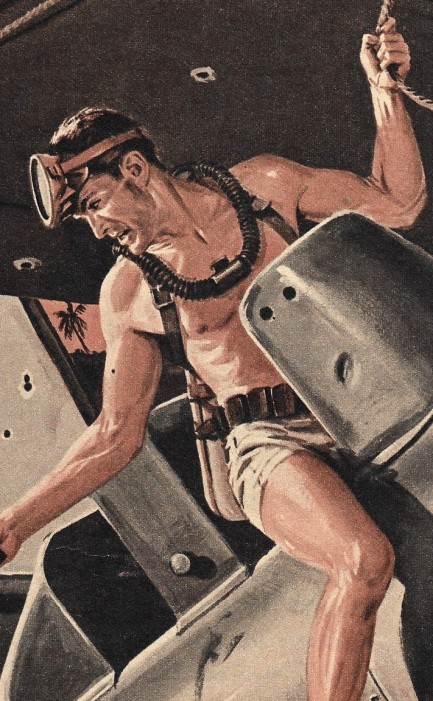

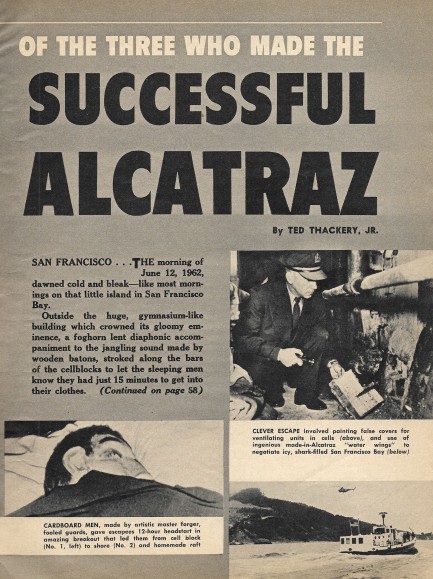

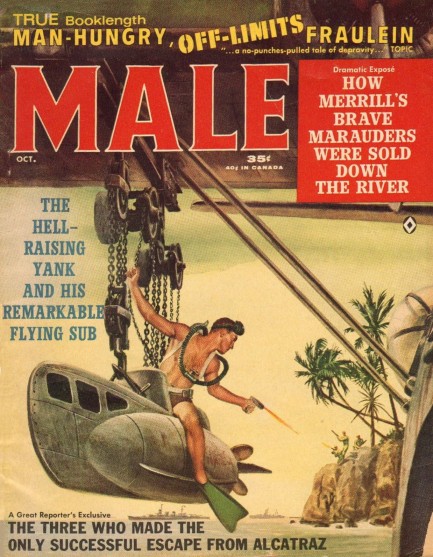

We're back to men's adventure mags today with an issue of Male from this month in 1962, with cover art by Mort Kunstler illustrating the tale, “The Hell-Raising Yank and His Remarkable Flying Sub.” We gave the story a read and it tells of Walter R. Cook, a U.S. soldier stranded in Burma who, with the aid of a local beauty (of course), finds and refurbishes an abandoned Catalina seaplane, which has attached to it a two man submarine. The sub was a type used during World War II that the operators rode like horses while breathing through scuba gear. Cook uses it to disrupt Japanese supply lines.

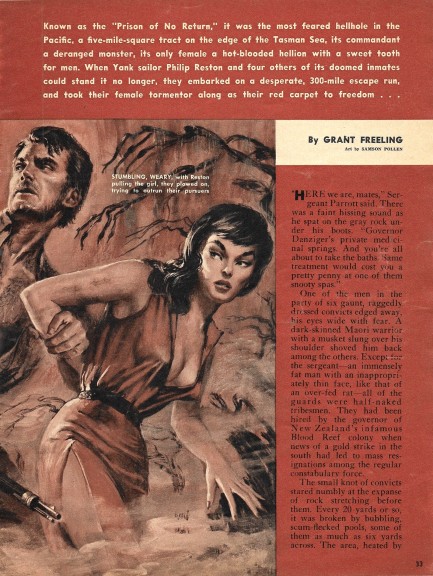

The story is a standard sort for an adventure magazine, but educational, since we'd never heard of rideable submarines. The illustration makes clear exactly what form it took. The magazine also offers stories set in China and New Zealand, and contains a detailed piece on an escape from Alcatraz, the very escape that inspired the Clint Eastwood film Escape from Alcatraz, involving the inmate Frank Morris, who may or may not have actually succeeded. The art throughout the issue is from the usual suspects—Charles Copeland, Samson Pollen, and Bruce Minney—and is tops as always. We have seventeen scans below.

Every flight was a one-way trip.

Above is a photo of a Word War II era Yokosuka MXY-7 Ohka, or “cherry blossom”—not a legit airplane, but rather a barely aerodynamic, wooden-winged, jet propelled craft released from on high and meant to be steered into enemy ships, whereupon the massive bomb that made up the nose of the ungainly contraption would detonate. Piloting one was considered a great honor, though few hit their targets due to their fragility and lack of maneuverability. These were dubbed by American servicemen “flying coffins,” for obvious reasons. This example was captured on Okinawa, which is why you see a “keep out” sign and a U.S. military policeman standing guard. The photo, which is one of the better ones we've seen, was published today in 1945.

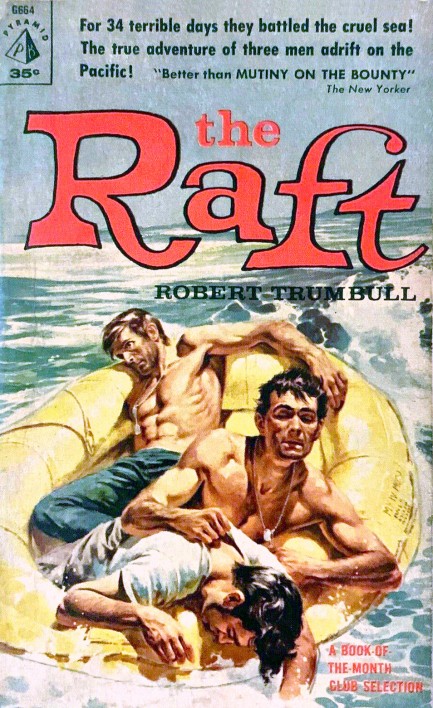

The only way to survive is by rationing. I've come up with a plan. First we'll eat him, then I'll eat you.

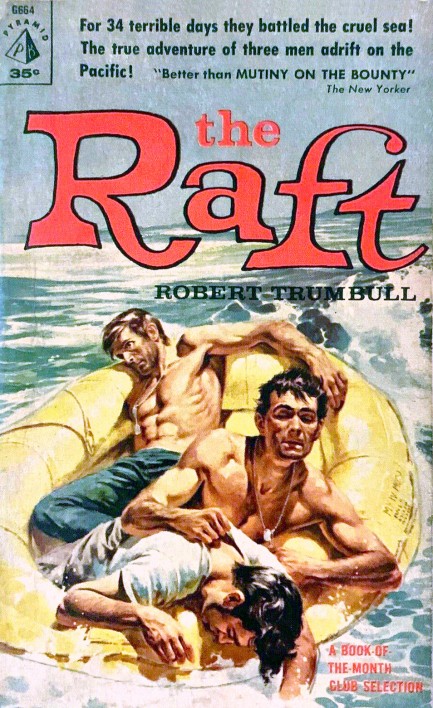

Well, our three castaways—Harold Dixon, Gene Aldrich, and Tony Pastula—are still floating on the high seas, and the situation has gone from bad to worse. They'll get out of this dilemma yet, though. Only a minor spoiler there, since The Raft—which details thirty-four days spent stranded at sea by three downed flyers—is a World War II biography, not a novel, and the tale is well known. But if you're unfamiliar with it, what you get is hot days, cold nights, constant soakings, several capsizings, a loss of gear, food, and hope, and an extraordinary—by which mean stranger than fiction—ending. This particular copy looks like it spent thirty-four days at sea too, but it's the best we could find.

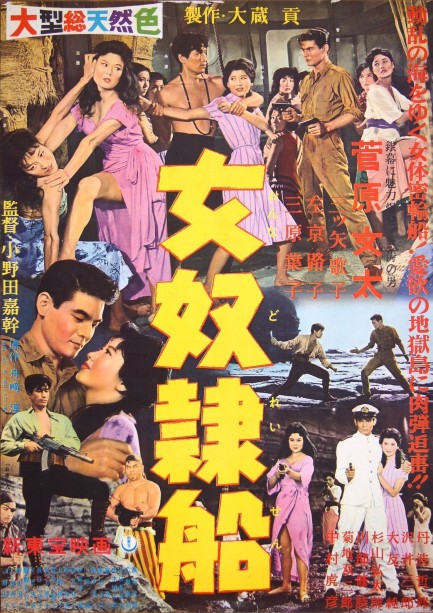

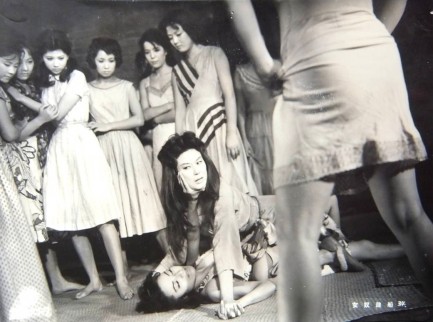

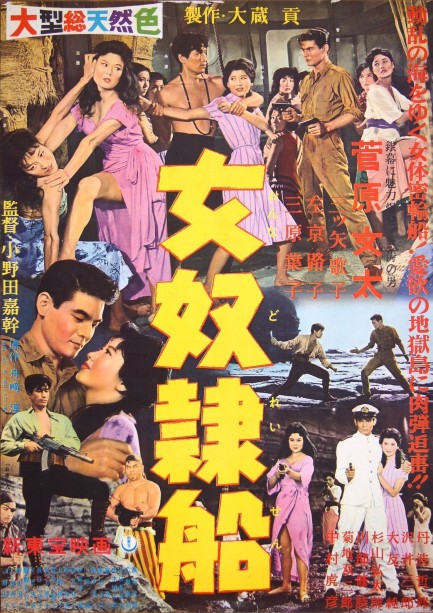

Sugawara gives the red light to wartime slavery.

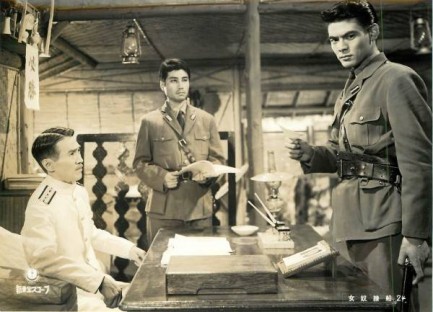

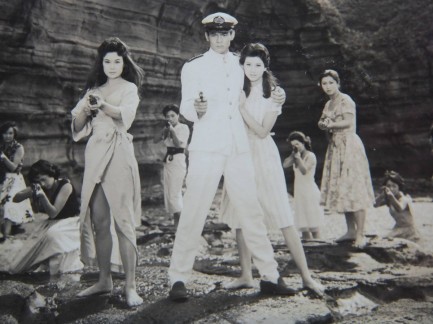

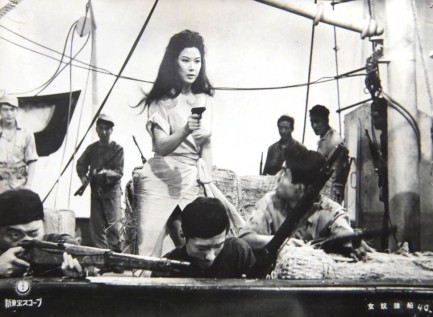

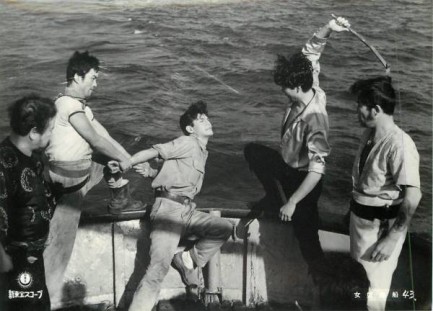

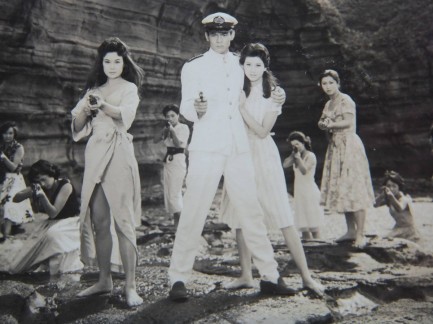

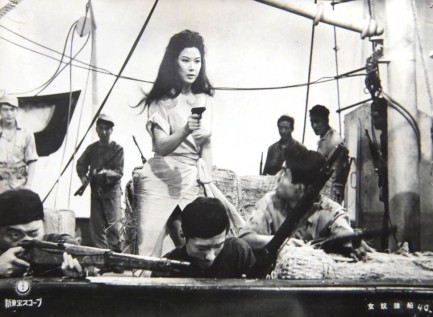

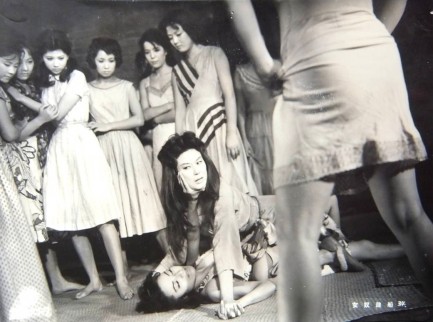

This blazingly colorful promo poster was made for the action movie Onna dorei-sen, known in English as Female Slave Ship, which is set during World War II and follows the adventures of a navy lieutenant played by Bunta Sugawara. The tale begins with him sent on a secret mission to obtain radar schematics to help salvage Japan's waning war fortunes, but unfortunately his plane is shot full of holes by a squadron of American F4Fs and he ends up in the drink. He's picked up by a Shanghai bound China boat, or slave ship, carrying twelve women meant to be auctioned to a gathering of Epsteins. Eleven of the women are prostitutes, but Rumiko, played by the lovely Utako Mitsuya, was tricked onto the boat. Naturally, she and Sugawara form an instant connection. Can he save her? You can be sure he'll try his best.

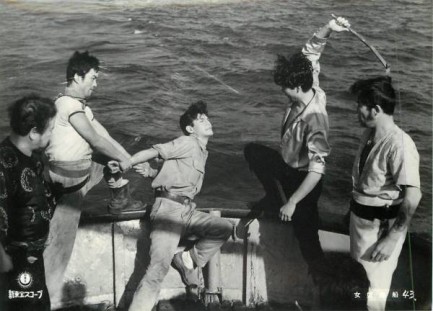

But just when you think Female Slave Ship is a straightforward white-knight-saves-damsel tale, the slave ship is attacked by pirates, and the women and Sugawara are suddenly at the mercy of the most ruthless band of unbathed thugs ever to steam the East China Sea. After some onboard drama the vessel lands, not in Shanghai but on a rocky Chinese coast where traffickers plan to brand and sell the women. This obviously can't stand, which means Buntawara must somehow throw sand in the gears. Why he's even alive at this point is a question. He's been nothing but trouble to the pirates, and the simplest solution would have been to toss him to the sharks. Failing to do that will be a costly and contusion making error.

We wanted to get away from Nikkatsu Studios' misogynistic roman pornos for a while and this effort from Shintoho Film fulfilled the requirement. Well, mostly. While generally tame, you'll rarely see so many women slapped around. But the treatment is meant to outrage. Mission accomplished. You will hate these traffickers. As for the movie overall, we suspect you'll like-not-love it. It's done in broad strokes, but as a sort of surf-to-turf soap opera it mostly works fine. Sugawara, who was soon to become a cinematic icon, has a charisma befitting his burgeoning status. And Yôko Mihara, already a big star at this point, is enjoyable playing a slippery slaver whose allegiances shift with the tides. She and Sugawara are worth seeing. Female Slave Ship premiered in Japan today in 1960.

|

|

The headlines that mattered yesteryear.

2003—Hope Dies

Film legend Bob Hope dies of pneumonia two months after celebrating his 100th birthday. 1945—Churchill Given the Sack

In spite of admiring Winston Churchill as a great wartime leader, Britons elect

Clement Attlee the nation's new prime minister in a sweeping victory for the Labour Party over the Conservatives. 1952—Evita Peron Dies

Eva Duarte de Peron, aka Evita, wife of the president of the Argentine Republic, dies from cancer at age 33. Evita had brought the working classes into a position of political power never witnessed before, but was hated by the nation's powerful military class. She is lain to rest in Milan, Italy in a secret grave under a nun's name, but is eventually returned to Argentina for reburial beside her husband in 1974. 1943—Mussolini Calls It Quits

Italian dictator Benito Mussolini steps down as head of the armed forces and the government. It soon becomes clear that Il Duce did not relinquish power voluntarily, but was forced to resign after former Fascist colleagues turned against him. He is later installed by Germany as leader of the Italian Social Republic in the north of the country, but is killed by partisans in 1945.

|

|

|

It's easy. We have an uploader that makes it a snap. Use it to submit your art, text, header, and subhead. Your post can be funny, serious, or anything in between, as long as it's vintage pulp. You'll get a byline and experience the fleeting pride of free authorship. We'll edit your post for typos, but the rest is up to you. Click here to give us your best shot.

|

|

Above you see a cover effort by Gerald Gregg for Helen McCloy's 1945 mystery The Man in the Moonlight. This is from Dell Publications, and you probably recognized it right away as a mapback edition. You see that here too, with its fictive university campus.

Above you see a cover effort by Gerald Gregg for Helen McCloy's 1945 mystery The Man in the Moonlight. This is from Dell Publications, and you probably recognized it right away as a mapback edition. You see that here too, with its fictive university campus.