Look at that view, men! Just think how much money a trip like this would cost us if we were civilians!

Donald Downes' World War II combat and espionage novel The Scarlet Thread originally appeared in 1953, with this Panther Book edition coming in 1959, adorned with cover art from an unknown. Like many mid-century war novelists, Downes saw it all firsthand. He was in the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI), the British Security Coordination (BSC), and the OSS (we don't need to decipher that one, right?), and saw action against the fascists in Italy and Egypt. This novel, his first, draws on those experiences in telling the story of an aviator sent on a mission to eliminate a suspected double agent. Its French translation won Downes the 1959 Grand Prix de Littérature policière. Mission accomplished.

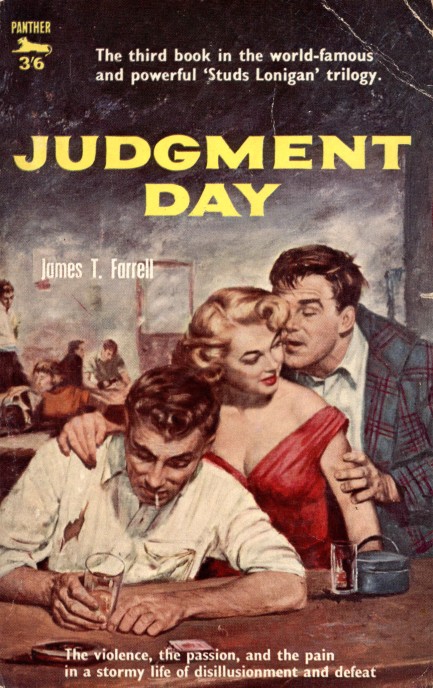

Forget that loser. I'm a man with prospects. Buy me a drink and I'll tell you all about them.

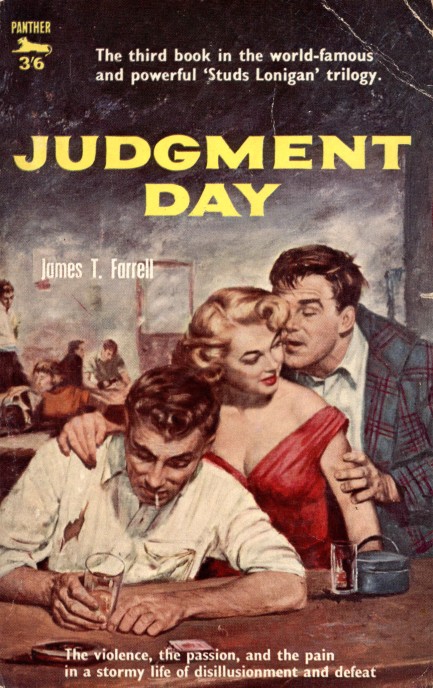

Above: an uncredited cover for Judgment Day by James T. Farrell, which neatly encapsulates the classic woman's dilemma—most guys who come up to you in bars are at least a little drunk. This book is another case of serious literature getting a pulp style cover as a retrofit. As the text notes, it was the third book in the Depression-era Studs Lonigan series, which is one of the more important literary products of the 1930s, and, like many pieces of politically shaded literature from then, was very critical of American capitalism. This Panther edition came in 1959.

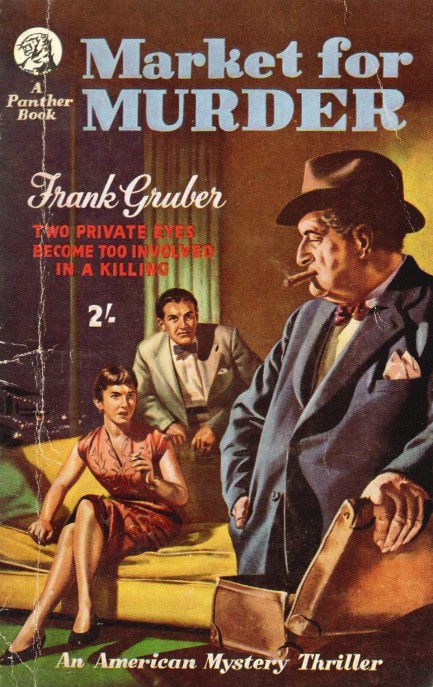

You're in the market for murder? Inside here I got everything harmful—guns, knives, poisons, Ayn Rand novels. Everything.

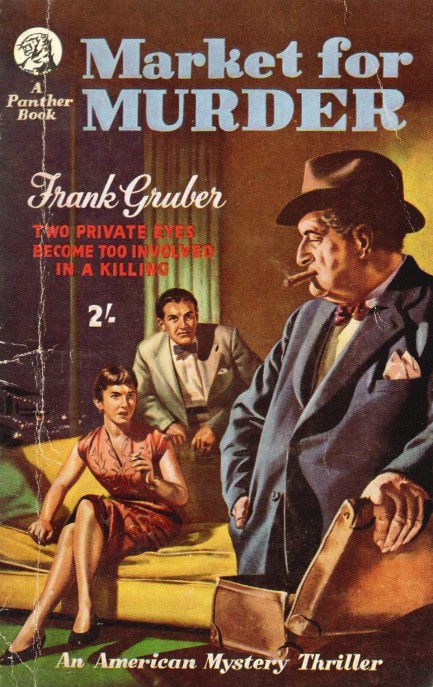

Above: a nice cover for Frank Gruber's 1947 mystery Market for Murder, from Panther books. We don't know who painted the art, but it looks a little like Josh Kirby, and he was occasionally working for Panther when this edition came out in 1956. But don't quote us, because we're guessing with not even fifty percent certainty. You can see confirmed Kirby here and here.

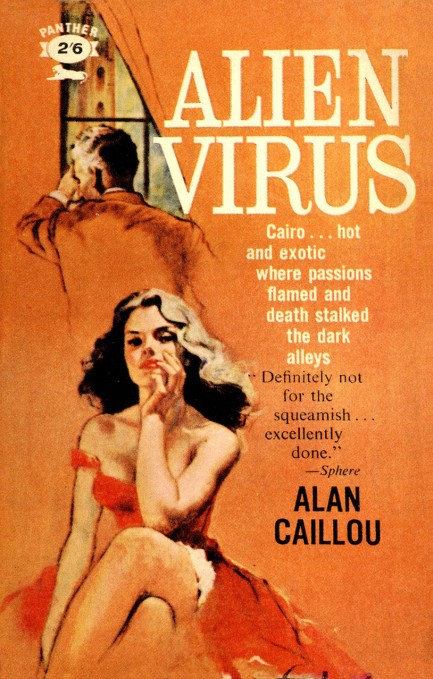

Can't stop the spread, can't hope to contain it.

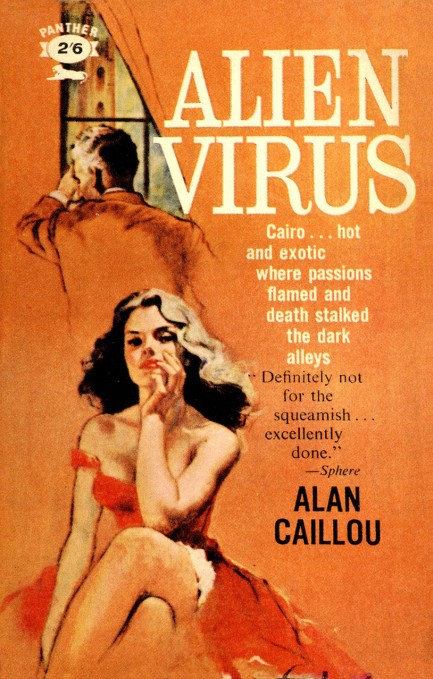

The colorful cover of this book attracted us, but the unusual title struck us too. Alien Virus? How could we resist that? The teaser tells us Alan Caillou's novel is a thriller set in exotic Cairo, so we were pretty sure the title was figurative and there'd be no viruses or aliens. We also learned from the rear cover that this is an espionage tale. When we cracked it open it became clear that, indeed, there is no literal virus. So then to what does the title refer? The book is set in Cairo before Gamal Abdel Nasser came to power in 1956, but sometime after the 1952 uprising that many historians consider a marker for the end of British rule there. Here's the passage that explains the title:

This was the way they would march, down from the big square to the wide streets and the midans, chanting their slogans, carrying their leaders on their shoulders, holding aloft their placards, and the [instigators] would watch and know just when to set the fires, and there would be shots in the dark alleyways, and a man would be kicked to death and the crowds would gather to watch the fun and then take part in the burning and the looting and the destruction and the killing, and bombs would be be thrown and men would be bleeding in the streets after they had passed. There was an alien virus at work.

Yep, Alien Virus is another glorification of empire, which posits that Brits deserved to steal and rule others' lands, with the violence used to do so neatly excised from the annals of western history, replaced by a myth describing colonials as pragmatic and occasionally firm rulers, but generally benevolent, and who of course transformed distant cultures in beneficial ways, and even left behind cricket and polo, invaluable gifts. But history—when those who've been subjugated and occupied are given a chance to speak—is not so clean or pretty as western books would have you believe, and plunderers cannot be heroes or saints.

Despite the point-of-view being colonial, Alien Virus is an entertaining tale. It was originally published in 1957, with this Panther Books edition coming in 1961, and was written by a man who knew Egypt well, understood the workings of both the western diplomatic service and the Cairo underground, and spoke the local languages. So confident is Caillou in his storytelling that he doesn't even bother to translate the numerous snippets of French and Arabic speech, preferring to impart meaning by mood, a high-minded literary choice unusual for the period as far as we know, and which even today is attempted only by the most self assured authors writing for the most understanding publishers.

There are several major characters in Alien Virus, but in the center of the action is Julius Tort, who catches wind of a serious destabilization plot, but at first can't figure out the where, when, and who of it all. Could it be Russians? Could it be a local religious faction? He may not know, but the reader certainly does, as Caillou gives glimpses into terrorist cells. He doesn't use that terminology, though, and the cells aren't very formal. They're just ragtag cabals, but armed and determined to see Brits out of their country. We won't reveal more. Instead we'll end with a fun dialogue exchange between the protagonists. It happens after a stabbing. The victim, Bolec, in addition to fresh knife wounds, has been suffering from hemorrhoids:

“A good job you have an appetite, my friend. Those spare tyres have saved your life. We'll have to put you in the hospital for a few hours.”

Perugino said maliciously: “Don't forget to have the doctor cut out your piles, Bolec. He might cut out your coglione at the same time.”

“All right, you wait, you get this thing, you not laugh about it.”

“Is strange, is it not?” Perugino mused, “Let us agree that the backside is the only intrinsically humorous object which is shared by both the nobility and the bourgeoisie. Bourgeoisie behinds have a different popular name, is it not so? But all the same, whatever you call them...”

Tort said: “A rose by any other name.”

“Whatever you call it, it is subject to same indignities and the same discomforts.”

“This is my backside you talking about!” Bolec shouted.

“If I were a wealthy man,” Perugino went on, “it would cause me a great deal of unhappiness to know that from at least one aspect I was no better than the common beggar. But as it is, I can find a certain comfort in it.”

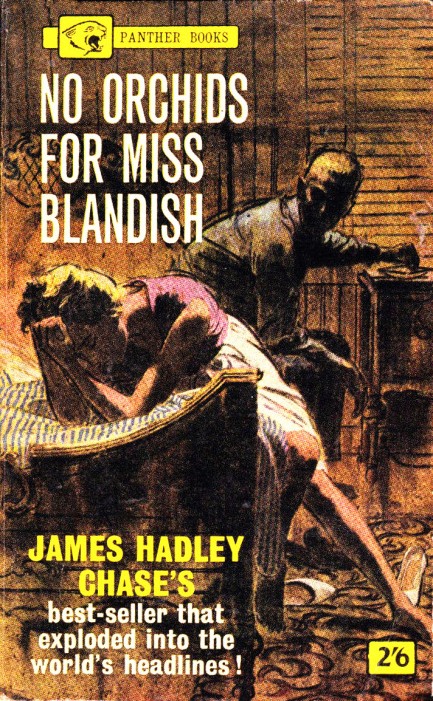

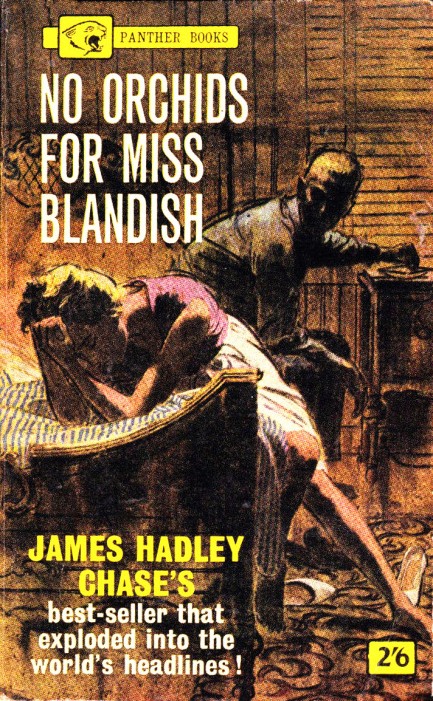

Chase is on in his blockbuster debut.

This 1961 Panther Books edition of James Hadley Chase's debut novel No Orchids for Miss Blandish labels it a bestseller that exploded into world headlines. That's quite a claim, but it's true. The book provoked a strong response when first published in 1939 due to its sexual frankness. Written in spare, hard hitting fashion, it's the multi-layered, uncompromising tale of the kidnapping of and search for the titular Miss Blandish, whose first name is never given despite her presence from beginning to end. There's violence, drugs, sexual content, and a lot of very low characters. Since we're pulp fans but not literary historians, we went into the book with no idea what it was about or that it was in any way significant, and came away immensely entertained and impressed. The highest compliment we can give it is that we were never sure who would win, or who would survive. Pair that with propulsive plotting and you end up with a must-read. World headlines? We believe it. Mitchell Hooks cover art? All the better.

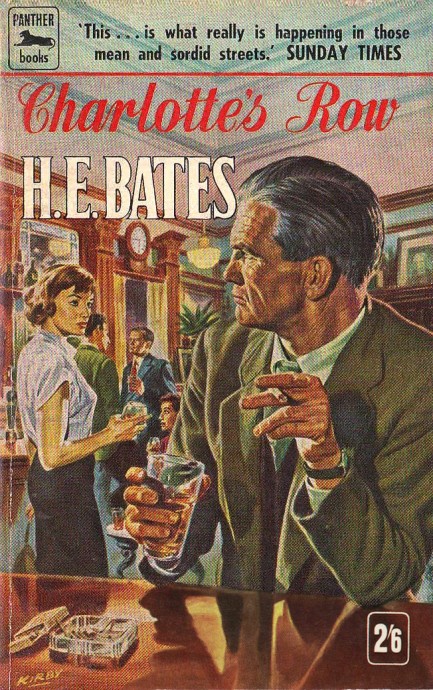

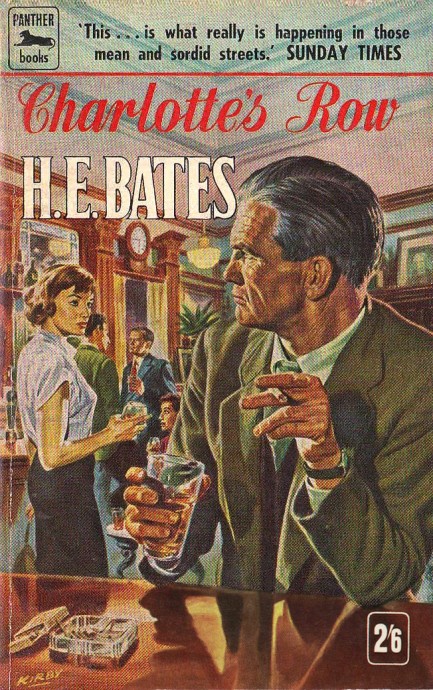

Hey everyone, I'm looking for a Master H.E. Bates. Is there anyone here who's Master Bates?

Author of numerous novels, short story collections, essays, and three—count 'em three—autobiographies, H.E. Bates has been described by numerous critics and peers as a master storyteller. Which makes him master Bates. We know—we're totally juvenile. We blame the booze. Also, he wrote a book called Spella Ho, a tricky grammatical proposition we've discussed in the past. There we go being juvenile again. It's inappropriate, because Bates was an important author who had major literary game and deserves a serious discussion. But not today. It's Friday. We have cava sangria chilling and the PI girls waiting. We will tell you, though, that Charlotte's Row is an early Bates novel, coming in 1931, and that this Panther Books paperback edition appeared in 1958. The story deals with an alcoholic bootmaker and his daughter, who live in poverty on the eponymous street. It's a detailed chronicle of the soulcrushing conditions in British factory towns around the turn of the last century, which is to say it's Dickensian rather than pulp, but we shared this anyway because we love the cover by Josh Kirby. We may or may not return to master Bates, but we will definitely see Kirby's excellent work again. For now, you can have a look at two more great examples of his genius here and here, and an entire gallery at his website here.

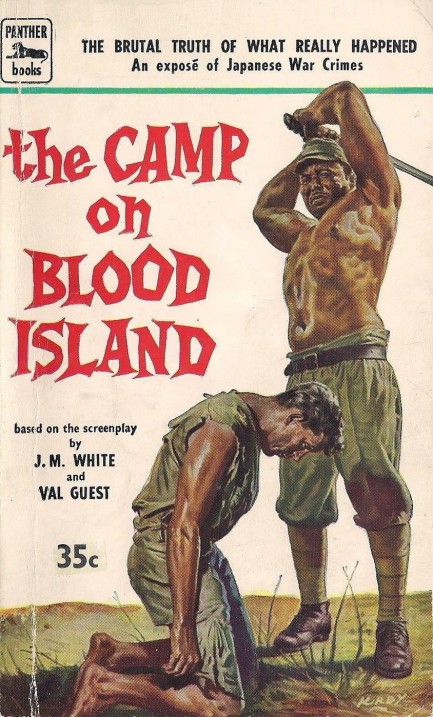

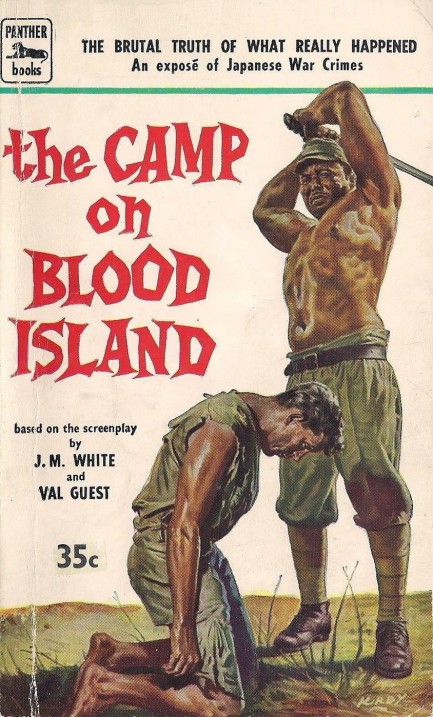

… two... and three. Wait. I screwed up again. That would've been on three and. I meant to do it on three.

Here's something backwards from what we usually share—a novel adapted from a film instead of vice versa. The Camp on Blood Island is a 1958 British-made World War II film written by J.M. White and Val Guest, and when you learn it was produced by schlockmeisters deluxe Hammer Film you could be forgiven for suspecting it was low rent b-cinema, but this is Hammer trying to be highbrow. Near the end of the Pacific War, a Japanese prison camp commandant decides that if Japan surrenders he'll execute all his prisoners. So the prisoners decide to prevent news of any prospective surrender from reaching the commandant by sabotaging communications, and they also prepare to rebel when the times comes. We may check the film out sometime, but we were mainly drawn by the paperback art. Not only did it remind us that prison camp novels are yet another subset of mid-century literature, but we saw the Josh Kirby signature on this one and realized we haven't featured him near enough. Last time we ran across him was on this excellent piece. We'll dig around for more. And we may also put together a small collection of prisoner-of-war covers later. They range from true stories to blatant sexploitation, and much of the art is worth seeing.

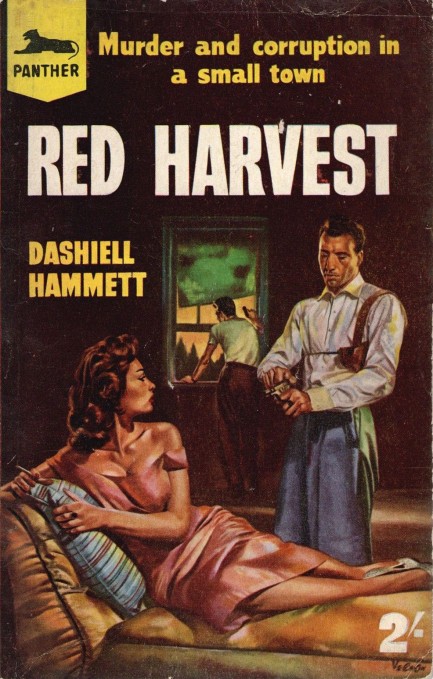

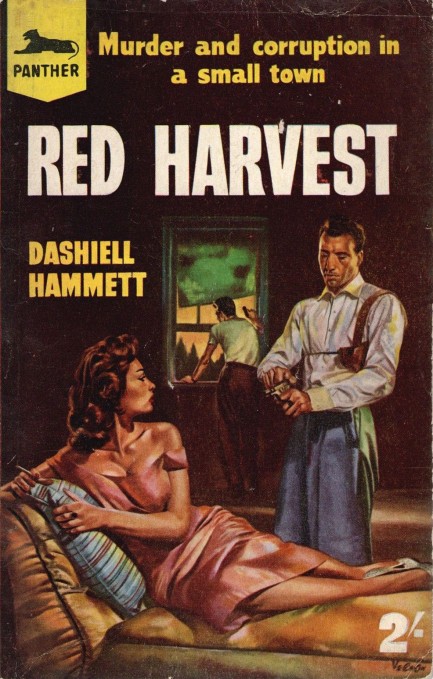

The most important safety precaution is to make sure the chamber on this baby is empty, or else disaster can—BANG!

The U.K. imprint Panther Books had some tasty covers during the mid-1950s, including this pretty effort by John Vernon for Dashiell Hammett's Red Harvest. We gave it a read and it involves Hammett's recurring character, a Continental Detective Agency operative, aka the Continental Op, being hired by a newspaper publisher who turns up dead before the two can meet. The subsequent investigation lifts the lid on corruption in a small town called Personville—but which locals call Poisonville. Hammett was a very solid genre author, with a spare, raw style, like this, from chapter seven:

It was half-past five. I walked around a few blocks until I came to an unlighted electric sign that said Hotel Crawford, climbed a flight of steps to the second floor office, registered, left a call for ten o'clock, was shown into a shabby room, moved some of the Scotch from my flask into my stomach, and took old Elihu's ten-thousand dollar check and my gun to bed with me.

After reading dozens of other (still very entertaining) authors since we last hefted a Hammett it was good to be reminded just how efficiently brutal he was. While the story is spiced up by a wisecracking femme fatale named Dinah Brand, the main element in Red Harvest is violence—a storm of it. By the end of the bloody reaping there are more than twenty five killings, as one player after another is knocked off. We rate Red Harvest the most lethal detective novel we've ever read. It was first published in 1929, with the above edition appearing in 1958.

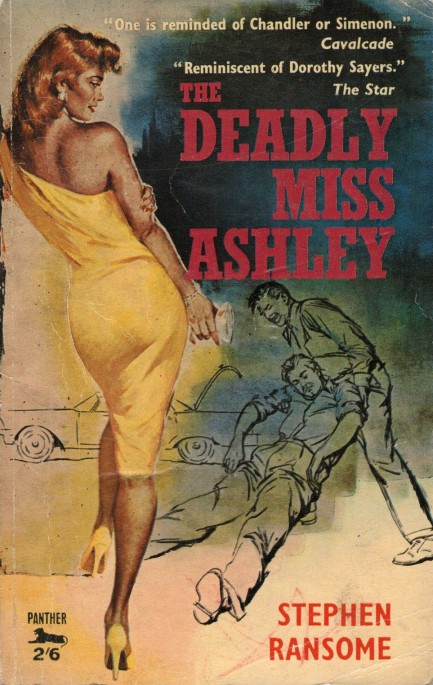

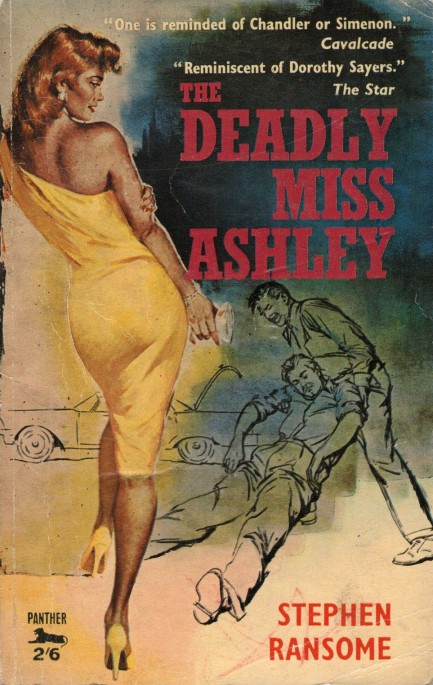

Help you drag him to the car? Are you high or did you simply not notice that my dress is Givenchy?

Artist Raymond Johnson offers up a great femme fatale on this cover for The Deadly Miss Ashley, authored by Stephen Ransome as the first entry in his Schyler Cole and Luke Speare detective series (gotta love those names). In this one Miss Ashley is actually a missing person who Cole and Speare need to locate. The book was originally published in 1950 in the U.S. under the writer’s real name Frederick C. Davis, with this Panther Books edition appearing in England in 1959.

|

|

The headlines that mattered yesteryear.

2003—Hope Dies

Film legend Bob Hope dies of pneumonia two months after celebrating his 100th birthday. 1945—Churchill Given the Sack

In spite of admiring Winston Churchill as a great wartime leader, Britons elect

Clement Attlee the nation's new prime minister in a sweeping victory for the Labour Party over the Conservatives. 1952—Evita Peron Dies

Eva Duarte de Peron, aka Evita, wife of the president of the Argentine Republic, dies from cancer at age 33. Evita had brought the working classes into a position of political power never witnessed before, but was hated by the nation's powerful military class. She is lain to rest in Milan, Italy in a secret grave under a nun's name, but is eventually returned to Argentina for reburial beside her husband in 1974. 1943—Mussolini Calls It Quits

Italian dictator Benito Mussolini steps down as head of the armed forces and the government. It soon becomes clear that Il Duce did not relinquish power voluntarily, but was forced to resign after former Fascist colleagues turned against him. He is later installed by Germany as leader of the Italian Social Republic in the north of the country, but is killed by partisans in 1945.

|

|

|

It's easy. We have an uploader that makes it a snap. Use it to submit your art, text, header, and subhead. Your post can be funny, serious, or anything in between, as long as it's vintage pulp. You'll get a byline and experience the fleeting pride of free authorship. We'll edit your post for typos, but the rest is up to you. Click here to give us your best shot.

|

|