| Femmes Fatales | Nov 19 2023 |

| Femmes Fatales | Aug 27 2022 |

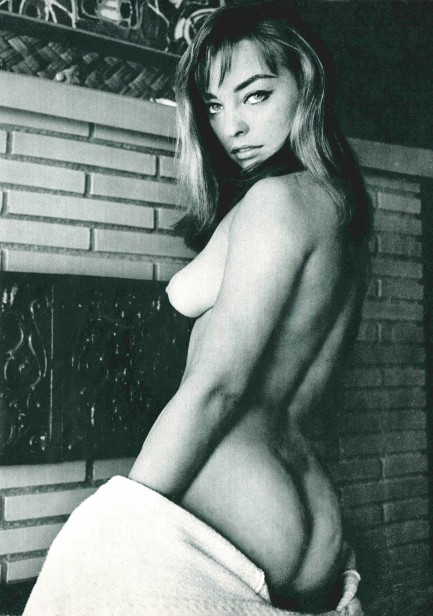

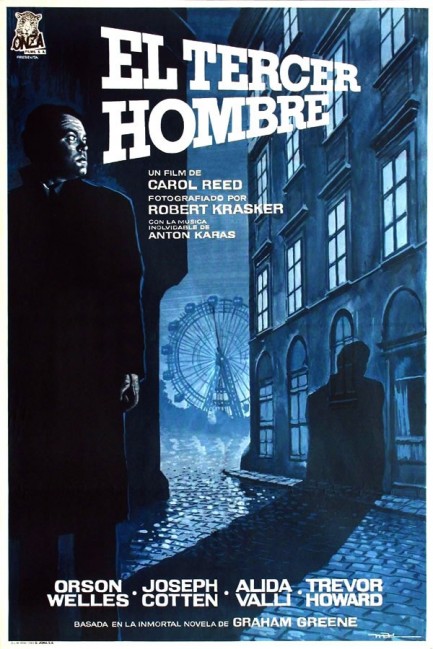

Her name is Ann Atmar. She's appeared here before, back in 2014 as part of an issue of Adam magazine, the U.S. version. She acted in three movies, including 1959's Street-Fighter, and several television series, one of which was the small screen serialization of the classic film noir The Third Man. You're thinking: “There was a series based on The Third Man?” Indeed there was, and Atmar graced a single episode. Sadly, she died early, in 1966 aged twenty-seven, which means her career never quite took flight. The above shot came from Girls of the World magazine, which is an all photo publication that as far as we know never had copyright dates inside. However, the magazine launched in 1968, which means Atmar's photo is posthumous.

| Vintage Pulp | Sep 18 2013 |

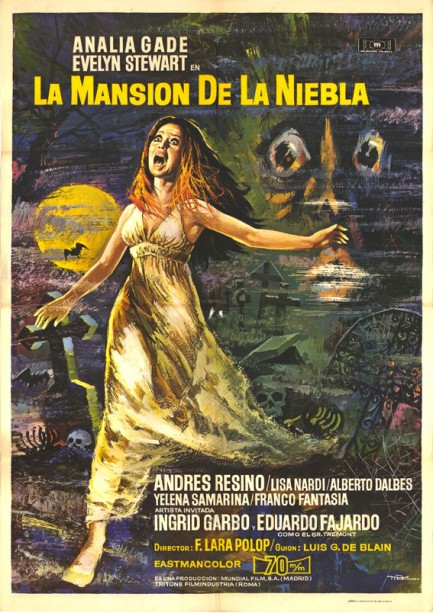

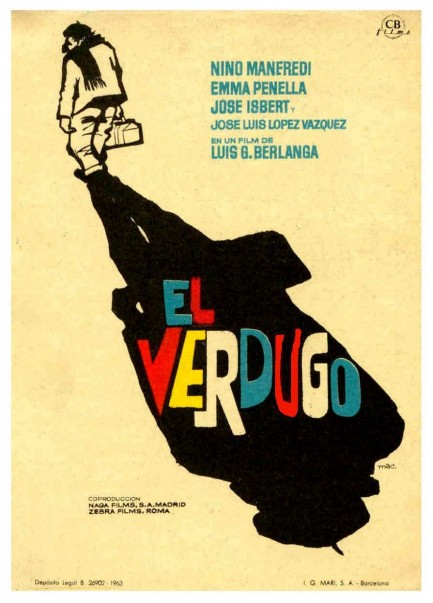

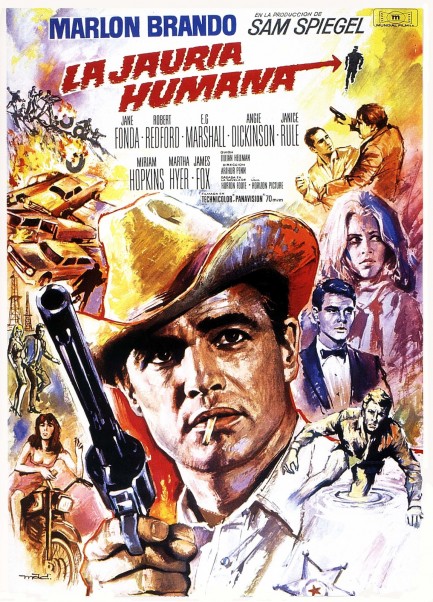

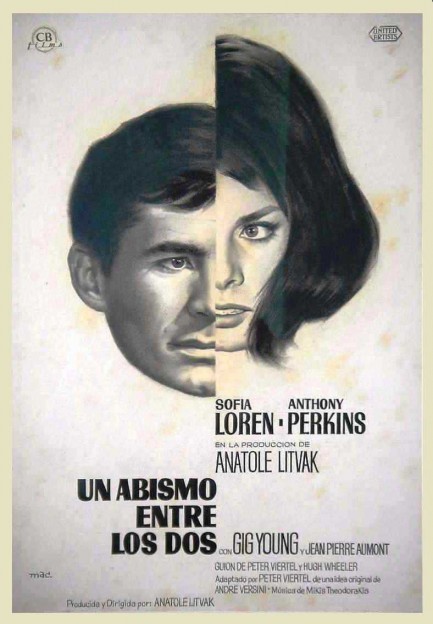

You can find plenty of amateur reviews of La mansion de la niebla, aka Murder Mansion, aka Maniac Mansion around the internet, so we won’t add another. We watched it, though, and basically, it’s about a bunch of people stranded in a fogbound manor house, and a plot to frighten one of them to death. Hope that didn’t give away too much. What really struck us was the poster, which was painted by an artist who signed his work Mac. Mac was short for Macario Gomez, and for four decades beginning in 1955 this Spanish painter created posters for such films as Dr. Zhivago, For a Few Dollars More, El Cid and others.

Gomez’s effort for La mansion de la niebla is a bit cheeseball, but we rather enjoy the numerous elements he managed to fit in, including a disembodied face, some skulls, a ribcage, a full moon, assorted gravestones, some random ironwork, a spider web, a bare tree, a couple of bats, and, of course, copious fog. Faced with all that, it’s no wonder the central figure is fleeing for her life. But just to show that Gomez really does have top tier talent, we’ve shared a few of his more successful posters below. La mansion de la niebla, an Italian/Spanish co-production, premiered as Quando Marta urlò dalla tomba in Italy, and in Spain six weeks later, today 1972.

| The Naked City | Vintage Pulp | Oct 7 2010 |

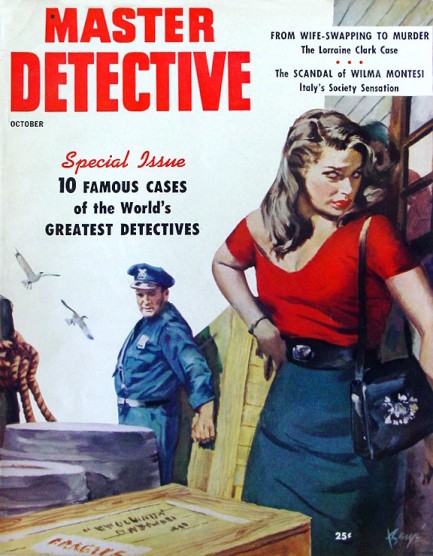

We double up on the murders today, thanks to the always informative true crime magazine Master Detective. This issue is from October 1954, with Barye Phillips cover art, and amongst the horrors revealed is one involving Massachusetts spouses Melvin and Lorraine Clark. The Clarks were heavy into key-swapping parties, at which opposite sexes blindly selected each other's keys from a bowl or sack to randomly determine who would be whose companion for the evening. If you’ve ever seen the Sigourney Weaver movie The Ice Storm, it was exactly like that—a few drinks, a few joints, and some freewheeling, no-strings-attached sex.

But when Melvin came home the night of April 10, 1954, and found Lorraine in bed with another man outside the context of a swapping party, an argument ensued that escalated to the point where Lorraine stabbed her husband with a knitting needle and shot him twice. She wrapped Melvin’s body in chicken wire, weighed him down with a cement block or two, and dumped him off Rocks Village Bridge into the Merrimack River, where the current was supposed to carry him out to sea.

She wrapped Melvin’s body in chicken wire, weighed him down with a cement block or two, and dumped him off Rocks Village Bridge into the Merrimack River, where the current was supposed to carry him out to sea.

Lorraine never expected to see her husband again we can be sure, and even filed for divorce as part of her cover story, claiming he had abandoned her after a bitter confrontation. But Melvin hadn’t abandoned her—in fact, he hadn’t gone far at all. A bird watcher found his mostly skeletonized body in a riverside marsh in early June.

Under police questioning Lorraine caved in pretty much immediately and, long story short, earned a life sentence in federal prison. She never named an accomplice, but no bodybuilder she, it seemed clear she could not have done the heavy lifting involved in the murder without a helping hand. Also, for someone who had little to no experience with firearms, she sure had good aim. Melvin had taken one in the forehead and one in the temple. But Mrs. Clark was not pressed to name a partner in crime, did her time in silence, and was eventually paroled. In retrospect, you wonder if local bigwigs wanted the case to go away. After all, you meet the most interesting people when you swap.

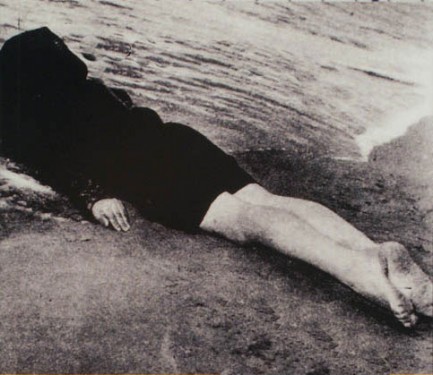

Master Detective treats us to a second fascinating story, this one on Italian fashion model Wilma Montesi, who in April 1953 was found dead on Plinius Beach near Ostia, Italy. Police declared her death a suicide or accidental drowning—case closed. But the public had many questions. How had she drowned in just a few inches of water? If it was suicide, why had she shown no signs of depression? Why were her undergarments in disarray? The police weren’t keen to reopen the case, but agreed to an informal re-investigation. Weeks later they announced once more: suicide or accidental drowing. But the public suspected cops weren’t trying to reach any other conclusion.

accidental drowning—case closed. But the public had many questions. How had she drowned in just a few inches of water? If it was suicide, why had she shown no signs of depression? Why were her undergarments in disarray? The police weren’t keen to reopen the case, but agreed to an informal re-investigation. Weeks later they announced once more: suicide or accidental drowing. But the public suspected cops weren’t trying to reach any other conclusion.

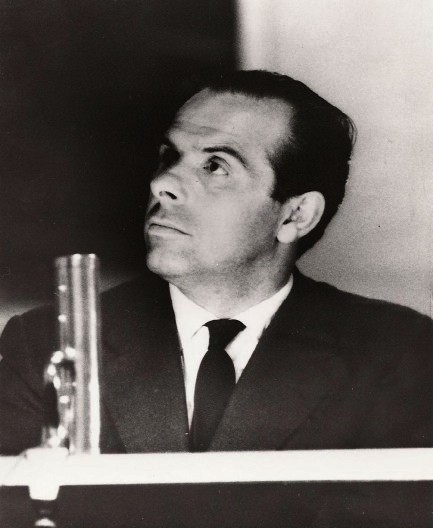

When the editor of the neo-fascist paper Attualita charged in print seven months later that Wilma Montesi had not gone to Ostia the day of her death, but to a fancy hunting lodge in nearby Capocotto, the story was not just ignored—Italian authorities hauled the editor before a court and threatened him with charges for spreading false information. But his tale was backed up by a witness—Anna Maria Caglio, who had spent time at the lodge and dropped a bomb on Italian society when she said it was a front for drugs and sex parties—sort of like The Ice Storm again, but with much richer and more powerful people involved. By powerful,  we're talking about judges, politicians, the Pope’s personal physician and other Vatican officials, and the well-connected Foreign Minister’s son Piero Piccioni, who you see pictured just above.

we're talking about judges, politicians, the Pope’s personal physician and other Vatican officials, and the well-connected Foreign Minister’s son Piero Piccioni, who you see pictured just above.

When the national Communist party began making waves, the carabinièri—Italy’s military police—stepped in. Like the local cops, they weren’t keen to pursue the case, but they weren’t about to let the Communists break it open and potentially expose the corruption of the entire political establishment. The carabinièri’s involvement angered many upper crust Italians, but when their officers walked the streets during those months the general public literally applauded them for daring to tread where the police had not.

Their investigation soon focused on Piccioni, who besides being the scion of a political family was a famous jazz composer. But Piccioni had an alibi—at the time of the murder he was in the house of actress Alida Valli in Amalfi, where he claimed to be sick in bed. Rumors sprang up that he was Valli’s lover. Why did anyone care? Because Valli, a big star at the time who had appeared in Orson Welles’ The Third Man, was married to another famous musician, Oscar de Mejo. The case was now a full-blown media circus.

This is the way it may have gone: every direction the carabinièri turned, politically connected Italians threw up walls in their path. Alternatively, it may have gone like this: the carabinièri made a noisy show of annoying a few heavy hitters, but were only performing for a suspicious and cynical public. What was clear  was very powerful people wanted the orgiastic activities in Capacotto forgotten.

was very powerful people wanted the orgiastic activities in Capacotto forgotten.

Behind the scenes manuvering was rife. Anna Maria Caglio even wrote a letter to the Pope warning him that there were people around him who meant him harm, presumably because they wanted to expose the involvement of Vatican officials in the late night shenanigans at the lodge. Pressure came down from the highest levels of the Italian establishment to put the case to bed quickly. It wasn’t quick.

But neither was it necessarily thorough. Eventually four people were brought to trial, including Piero Piccioni. All were acquitted. Perhaps the only consequence of the investigation is that it became one of the most celebrated mysteries of all time, inspiring many books, and even a symbolic reference in the incomparable Federico Fellini film La Dolce Vita. But what really happened to Wilma Montesi? Nobody knows. Today the case is still unsolved.

| Vintage Pulp | Mar 2 2009 |

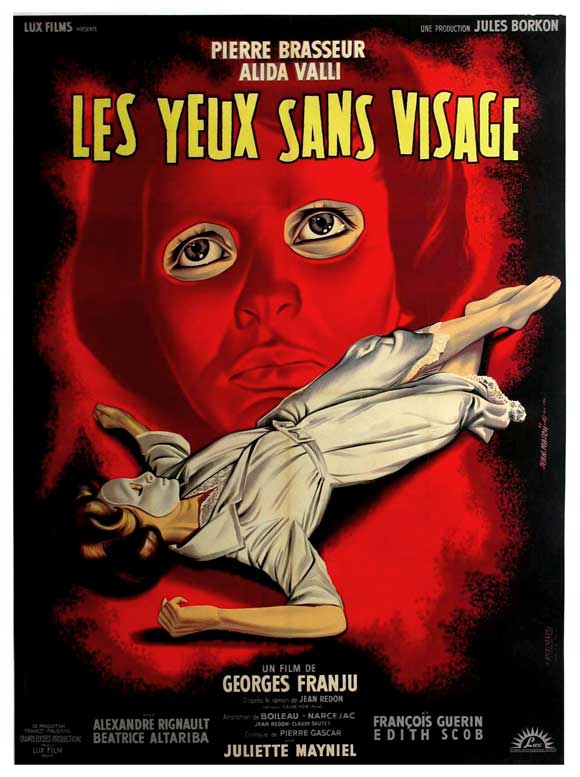

Les Yeux san visage, aka Eyes without a Face, is a macabre, artful and surreal French film about a plastic surgeon, played by Pierre Brasseur, who is obsessed with finding a new face for his disfigured daughter. Like most mad scientists, Brasseur is worthy of both pity and scorn, as his corrosive guilt over having caused the accident that ruined his daughter's life drives him to steal faces from other women. Every mad scientist has a sidekick, and here the role is ably filled by Alida Valli, who noir buffs remember from Orson Welles’ great The Third Man.

A scheme involving kidnapping women and stealing their faces has to go awry at some point, but to find out what happens you’ll have to watch the film. In the meantime enjoy the brilliant promo art, which comes in two versions, both featuring disfigured Edith Scob gazing forlornly from behind a white mask. Les Yeux san visage received mixed reviews when it opened, but art has a way of outlasting critics, and now director Georges Franju’s brooding little horror tale is an acknowledged classic. It even inspired Billy Idol to write a hit song—and that can't be bad. Les Yeux san visage premiered in France today in 1960.