Wherever you look, there it is.

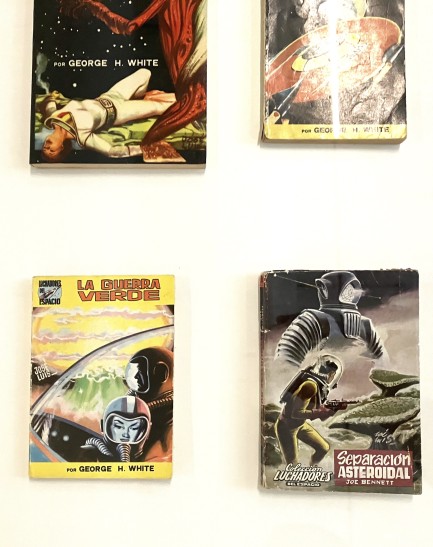

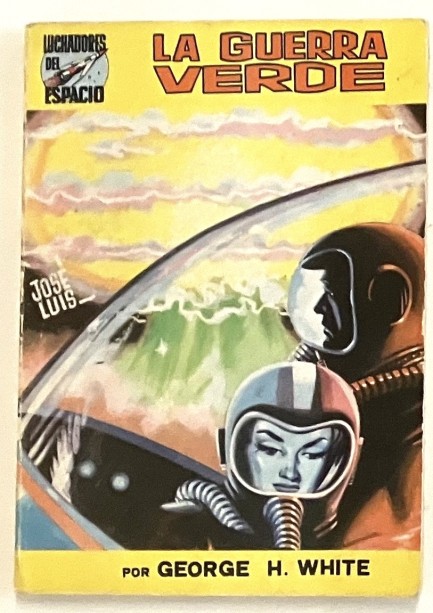

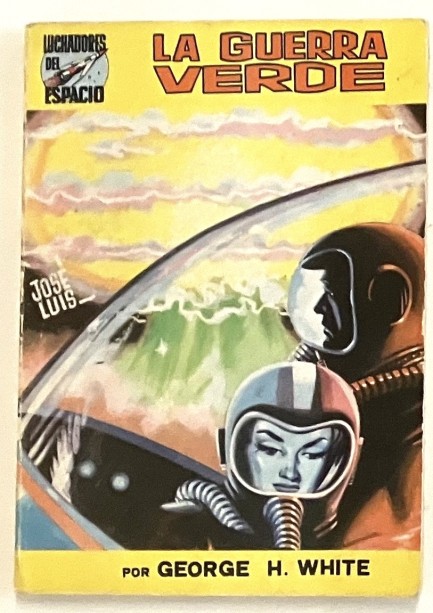

We're back. We said we'd keep an eye out for pulp during our trip to Donostia-San Sebastián, and we did see some, though we couldn't buy it—it was all under glass in a museum. The Tabakalera (above), a cultural space mainly focused on modern art, was staging an exhibit titled, “Evil Eye - The Parallel History of Optics and Ballistics.” A small part of the exhibition was a selection of Editorial Valenciana's Luchadores del Espacio, a series of two-hundred and thirty-four sci-fi novels published from 1953 to 1963. We snuck a few shots of the novels, which you can see below. Overall, though, what was on offer were photos, short films, political literature, and physical artifacts dealing with war and conflict. Since the participants were all artists, journalists, and witnesses from outside the U.S., everything naturally focused on wars that the U.S. started or sponsored—those ones they don't teach in school. The pulp fit because of its suggestion that human conflict would continue even into outer space.

We also said we'd try to pick up some French pulp, and that side trip happened too. We managed to score several 1970s copies of Ciné-Revue that we'll share a bit later, and those will feature some favorite stars. Though the collecting was fun, we're glad to be back. The birthday party was a success, as always, and now we're down south where the weather is gorgeous and hopes are always high. We'll resume our regular postings tomorrow.

Master of all he surveys.

We wanted to do a small post on Kirk Douglas, who died yesterday at the astonishing age of 103, but we took time to look around for a unique photo. This shot shows him in one of our favorite cities, Donostia-San Sebastian, standing atop Igeldo (or Igueldo), one of the seaside town's several large hills. He's looking toward the Bahia de la Concha with the Torreón de Monte Igueldo at his back. It's a majestic shot, fitting for such an icon, far better than showing him greased up as Spartacus, in our opinion. It was made in 1958 when he was attending the sixth Zinemaldia, aka the San Sebastián Film Festival, which was showing his film The Vikings. We don't generally do posts on Hollywood deaths. Why? Because there are so many. Anyone who loves vintage film knows that significant performers, writers, and directors are dying regularly, and we don't want Pulp Intl. to become an obituary roll. But for Kirk Douglas, one of film's all time greats, a consummate actor, an indispensable film noir bad guy, all the rules must be broken. See another max cool image here.

The learning is in the journey.

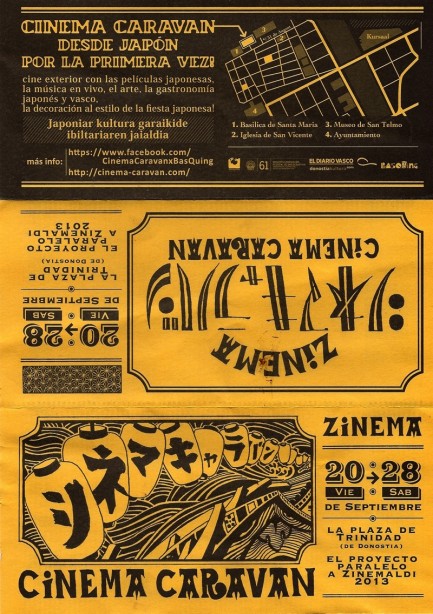

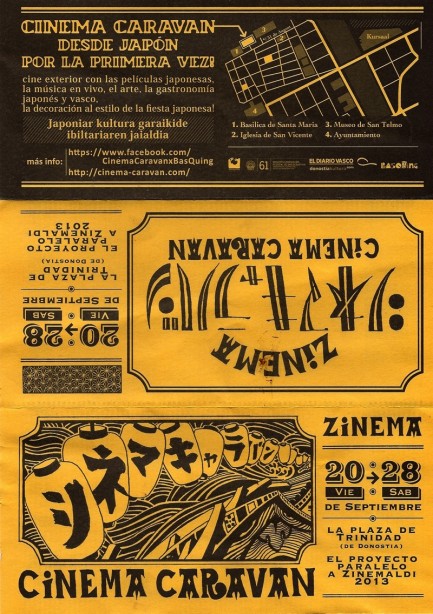

Last night’s finale of Cinema Caravan was probably the best evening of the weeklong festival. Organizers screened several short films, then the excellent band Cro-Magnon turned the event into an outdoor dance party, playing in a corner of the plaza as bottles of sake offered up gratis by festival organizers were passed from hand to eager hand. Over the course of the week we learned that Cinema Caravan is well established in Japan, migrating from city to city like a moveable feast for the senses, but that this is the first time it has been held in another country. The Basque Country doesn’t have a very large Japanese community, which made the week a real novelty for many here—the food, the drink, and the excellent music were revelations, but it was watching the films that imparted at least a token understanding of Japanese cultural values. By watching movies people learned what a culture from the opposite side of the planet finds humorous, or erotic, or frightening, or thrilling. If Cinema Caravan were to visit the amazing city of San Sebastian again it would certainly be welcomed with open arms. Meanwhile, there’s another film festival going on right now—the San Sebastian Film Festival, or Zinemaldia, which ends tonight and will bring another crescendo of activity to this city by the sea. We didn’t attend any of that festival’s events, but who knows—maybe next year. Below are a few shots from the week.

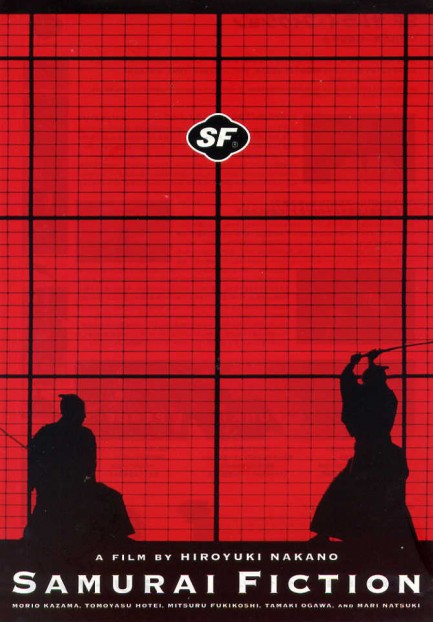

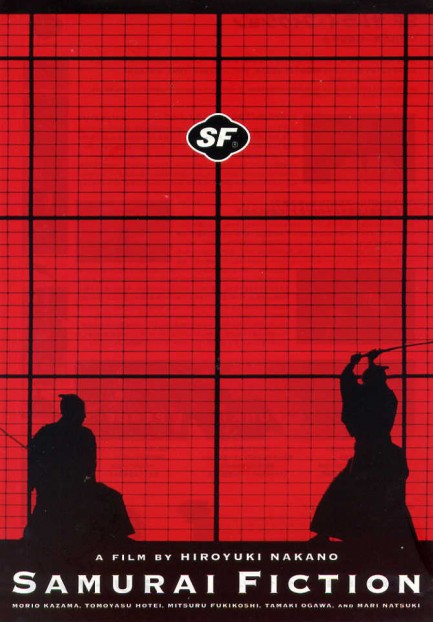

Hiroyuki Nakano’s sword opera Samurai Fiction challenges festival audience but ultimately leaves it satisfied.

San Sebastian in general and Cinema Caravan in particular are keeping us busy, but we have time for a quick post, so here we go. Last night we attended a screening of Hiroyuki Nakano’s 1998 adventure/comedy SF: Episode One, also known as Samurai Fiction. It’s a quirky movie, imaginatively shot mostly in black and white, and involves a young samurai on a mission to both avenge a friend’s death and retrieve a priceless sword. He encounters an ex-samurai who tries to teach him the wisdom of non-violence, with limited success. The movie is set in 1689 and looks a bit like Kurosawa’s great period pieces, but subverts that similarity with its humor and modern rock 'n’ roll soundtrack. Since it was in Japanese with English subtitles, the mostly Basque audience was perhaps a bit baffled, but even those with language difficulties could enjoy the film’s visual creativity, and ultimately everyone seemed to enjoy it.

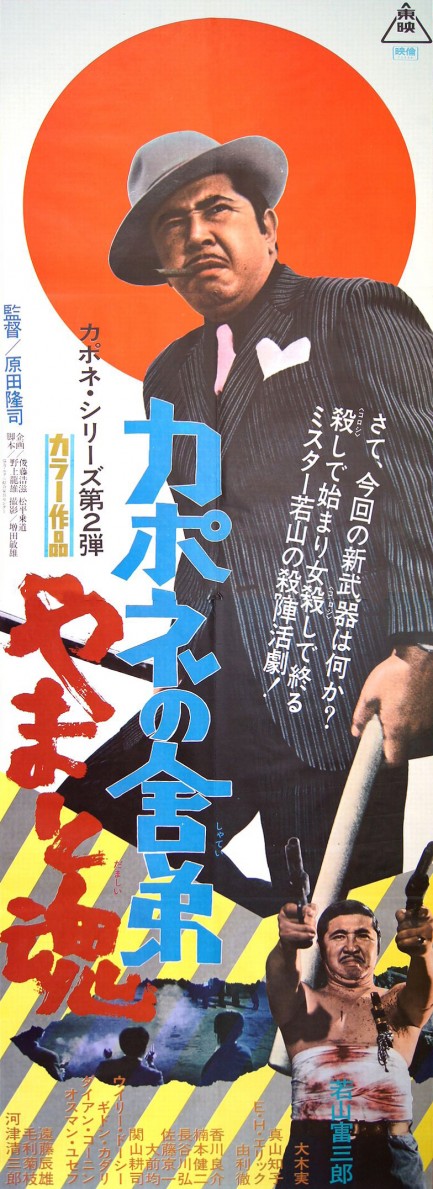

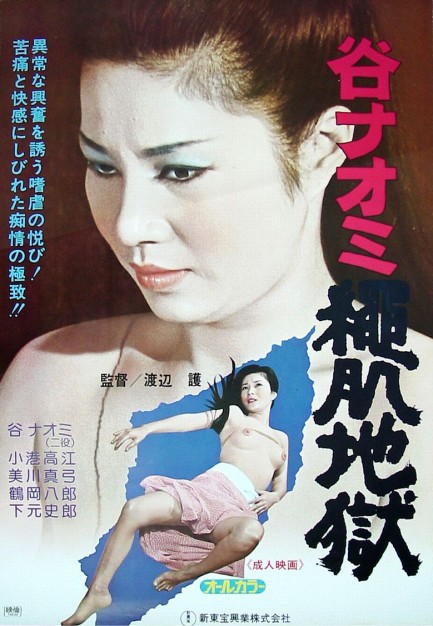

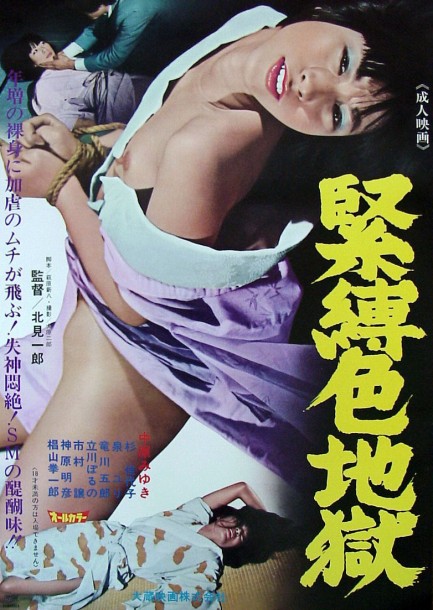

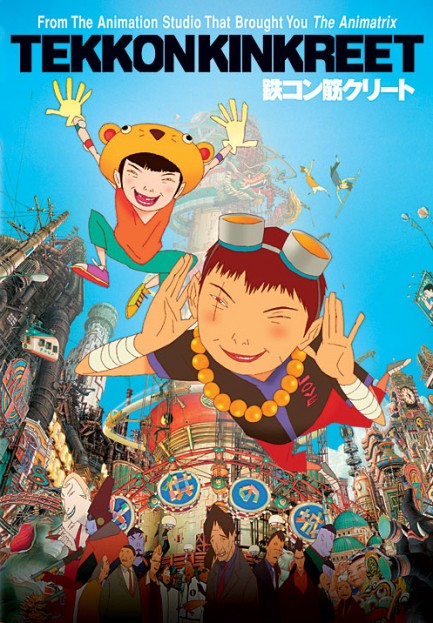

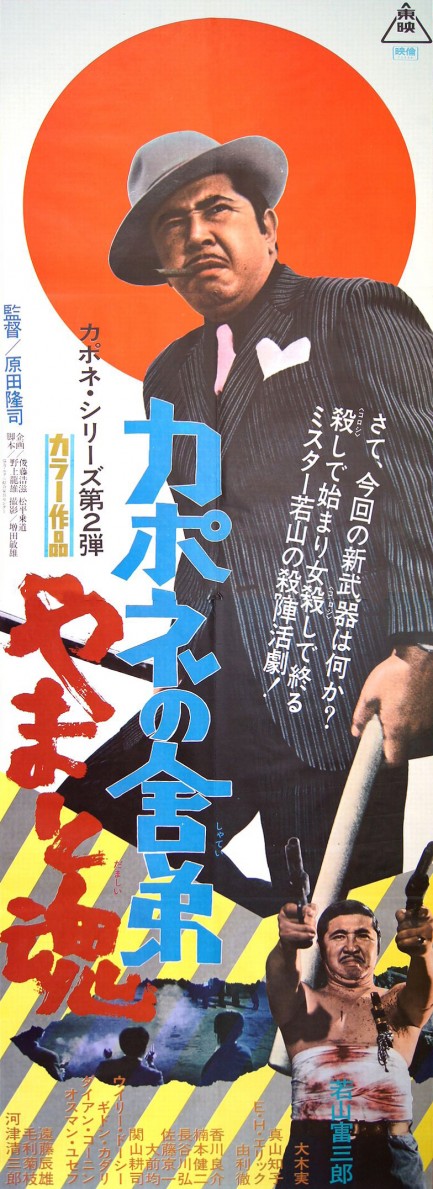

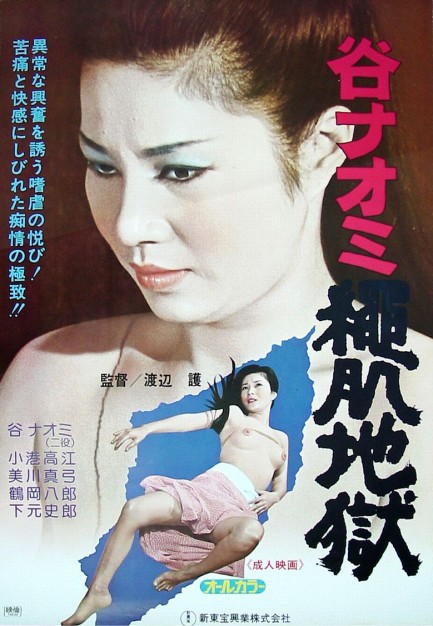

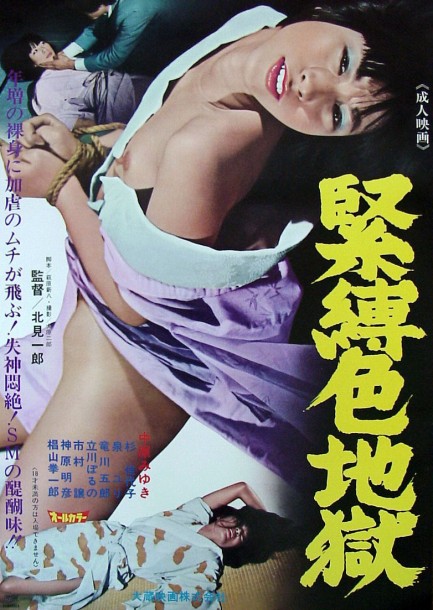

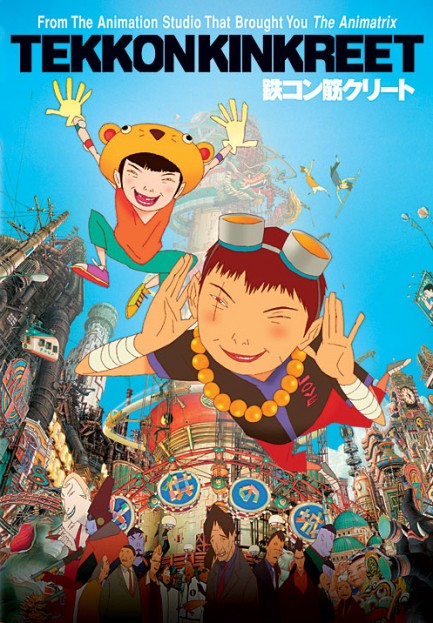

Watching Samurai Fiction got us thinking about our many Japanese posters, and because we actually have access to that stuff wherever we go, we decided to share five of the nicer pieces in our collection. In terms of information on these, time is a little tight to research them carefully, but here’s what we know: poster one—nothing; poster two—Nawa Hada Jigoku: Rope Skin Hell, with Naomi Tani, 1979; poster three—we’re unsure on that one, but that’s definitely Kayoko Honoo in the art; poster four—Kapone no shatei, yamato damashi, aka A Boss with the Samurai Spirit, with Tomisaburô Wakayama, 1971; poster five—nothing. But we'll see if we can find something about that one. See ya soon.

Black and White in color.

Cinema Caravan continued last night with a screening of the 2006 anime hit Tekkonkinkreet, which is based on a best-selling seinen manga series by Taiyö Matsumoto about two orphans named Black and White living in a dystopian place called Treasure City. In the main plot, Black and White battle against Yakuza that want to come in and take over the city. From the poster you can get a sense of how dizzingly dense Treasure City’s urban landscape is, which serves as a nice backdrop for various chases, battles with robot assassins, and a confrontation with the dark side of the self in the form of a minotaur. Don’t ask—just see it. The name of the movie (and manga) is a play on the Japanese words for steel reinforced concrete, which is "tekkin konkurito," or something like that. The film may be animated, but seinen manga are aimed more or less at an adult audience, so have no fears about this being like a Disney movie. Anyway, there’s plenty about Tekkonkinkreet online so we’ll stop at this juncture. Tonight, Cinema Caravan screens something called Samurai Fiction, which sounds promising. We’ll let you know how that is. Below is a really shitty photo from the festival. Note to selves: invest in a real camera.

Japan invades the Basque Country.

This week the ever-growing San Sebastian Film Festival in the Basque Country of Spain kicked off with the usual round of premieres at the city’s Kursaal and celeb walks along the seafront on Zurriola Beach. But in the city’s old quarter in a plaza tucked between an old church, some residential buildings, and a wooded hill, a group of Japanese deejays, musicians, foodies and cinephiles launched a weeklong festival-within-a-festival they’re calling Cinema Caravan. Last night the bill included a classic Nikkatsu roman porno, the 1973 Tatsumi Kumashiro comedy Yojôhan fusuma no urabari, aka The World of Geisha, starring Junko Miyashita. The film was projected outdoors while a Bedouin-style tent served as a bar/club, and two Japanese bodegas dished up soba noodles and fish. Before and after the movie the Japanese singer Naoito played beautifully, and the rest of the time world-class deejays spun tunes. All this in a plaza redecorated to resemble to a Japanese garden. The San Sebastian Film Festival is a worthy event, and this year’s version has stars like Hugh Jackman and Jake Gyllenhall, but it’s also expensive and chic and probably off-putting to some. Cinema Caravan, by contrast, is intimate and inclusive and everyone can feel a bit important. The event’s website says it best: Unfurling a screen for outdoor viewing in the different landscapes of our journey, we set the stage of non-routine experience in an everyday place. And in the process, we learn from those we meet on the road, their wisdom on how to live, and experience their varied cultures. Pulp Intl. is here all week, and if you’re in this part of the world (interestingly, our analytics tell us Spain is Pulp Intl.’s fifth most popular country) then consider stopping by. The festival runs through Saturday night with more movies, food, deejays, live music, dance, and fun.

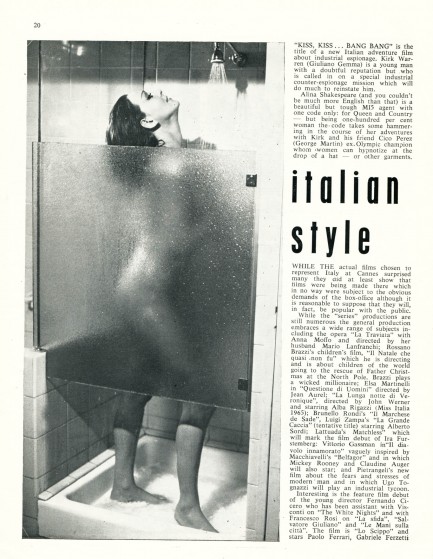

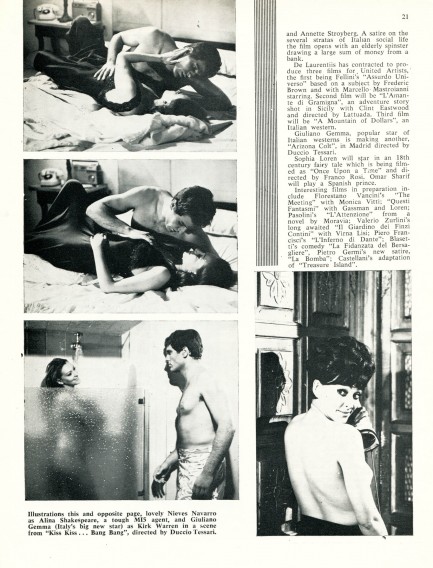

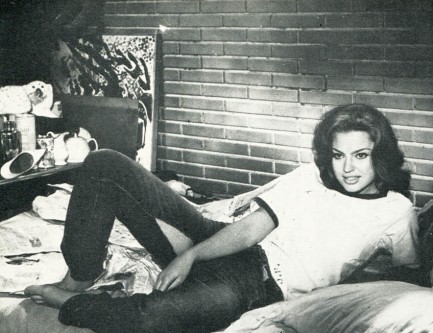

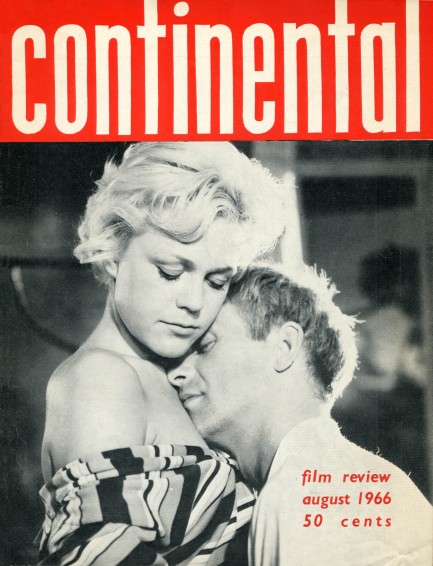

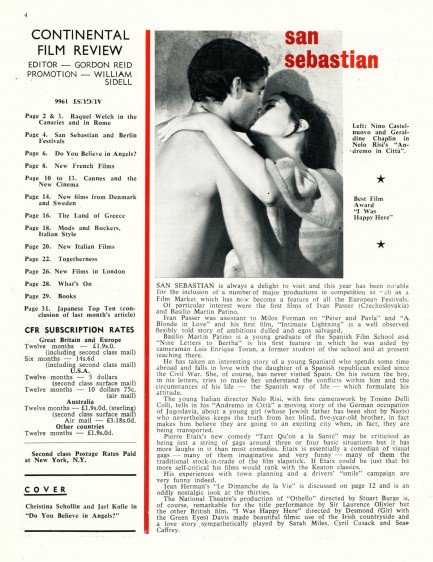

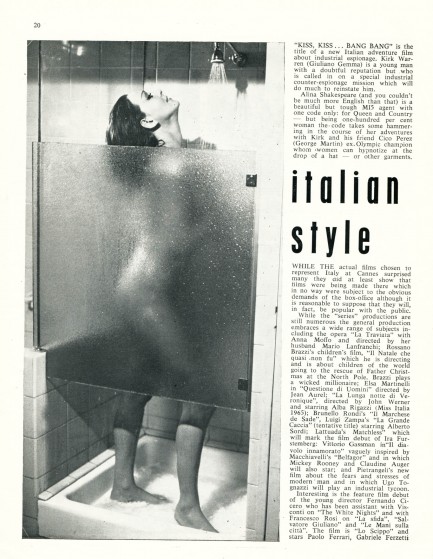

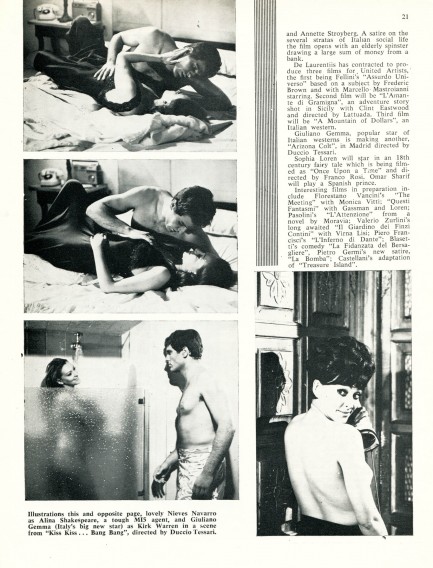

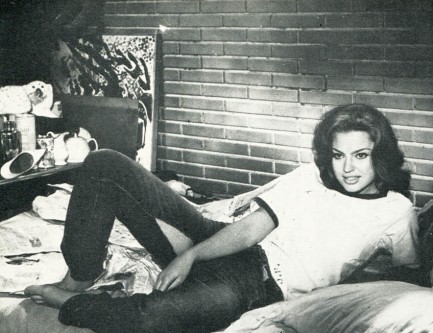

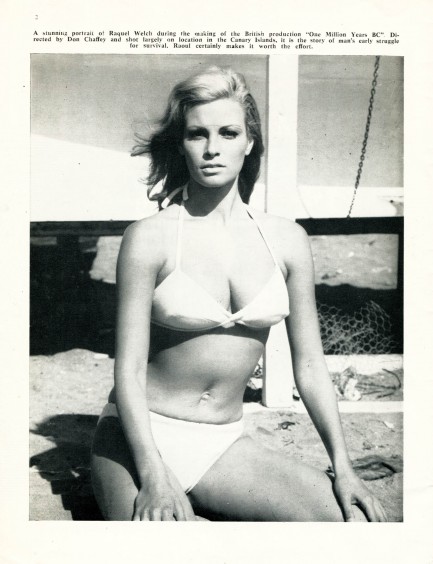

Continental Film Review was a leading voice of foreign film in Britain, as well as a leading source of cheap thrills.

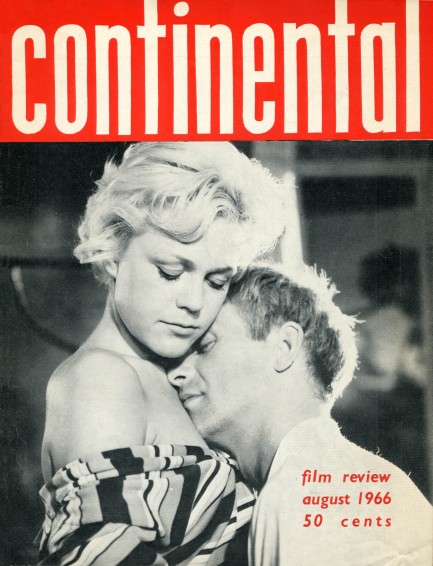

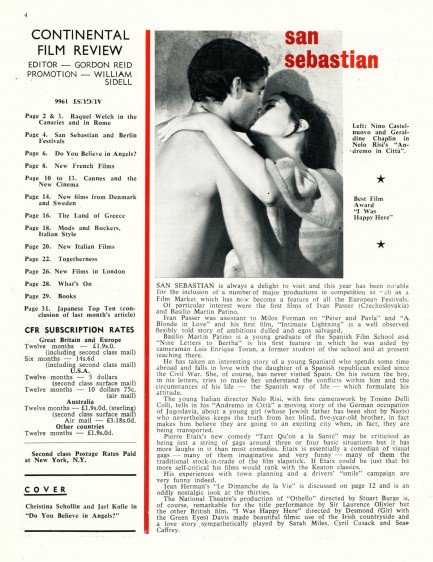

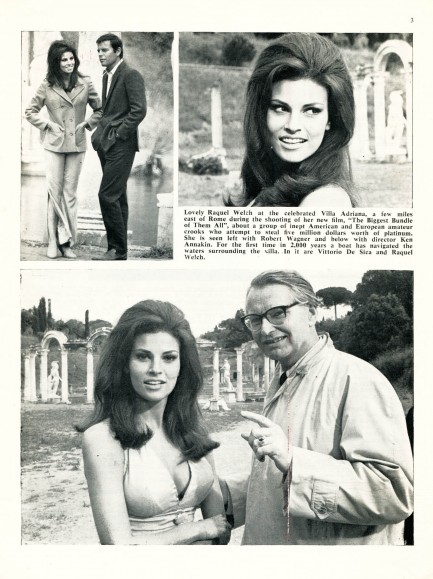

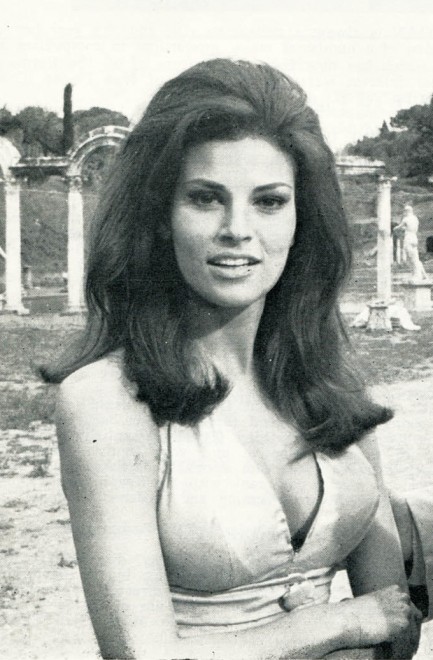

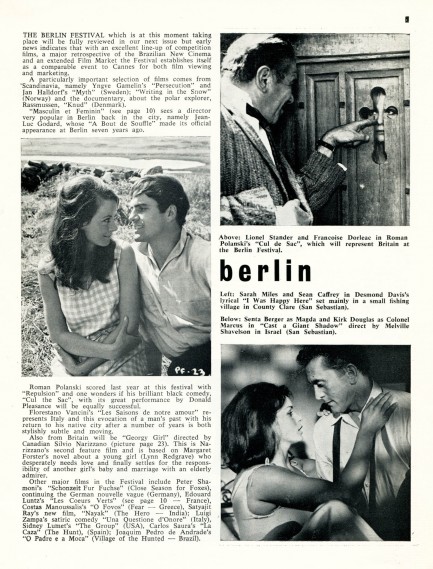

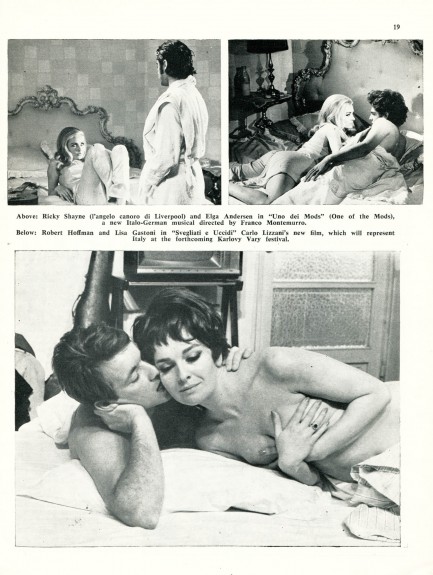

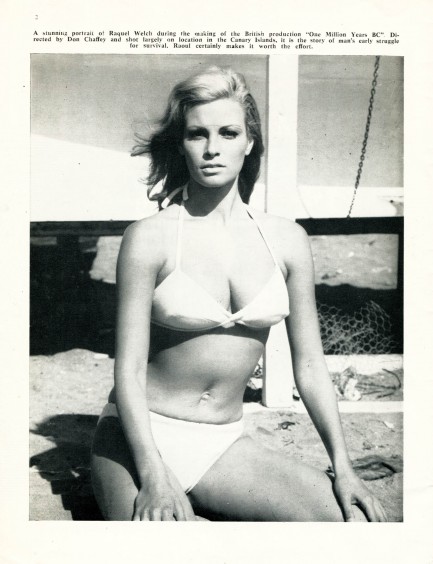

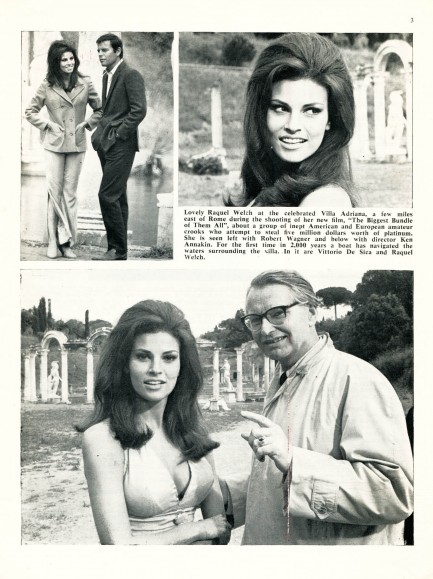

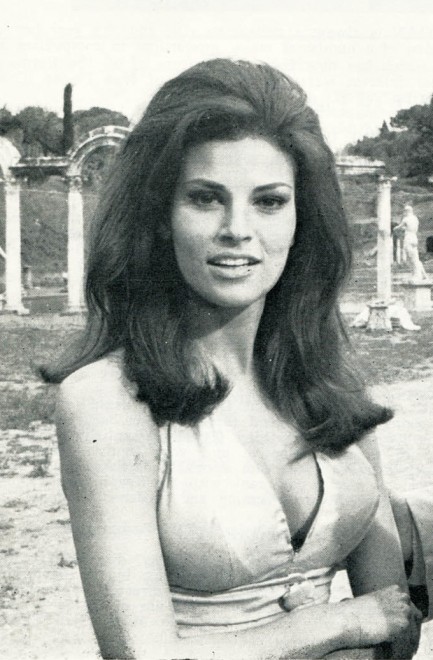

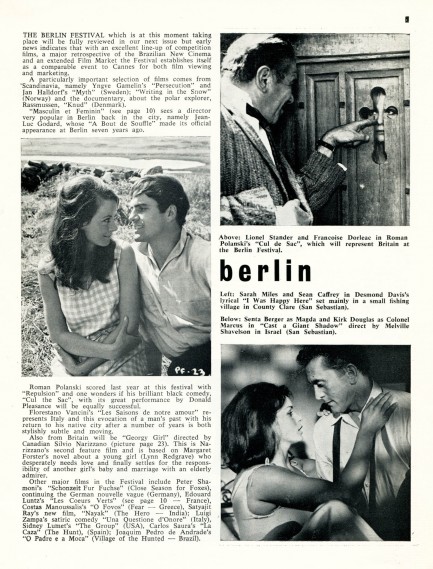

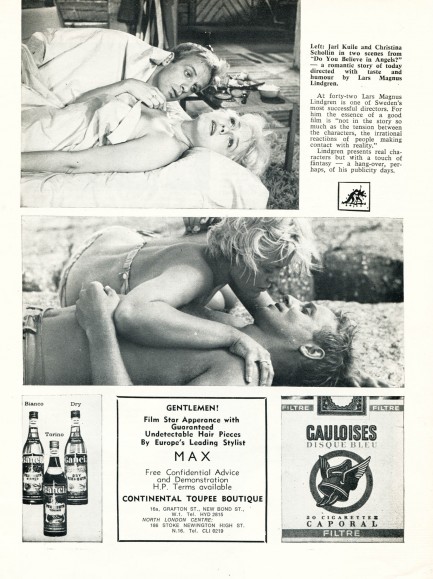

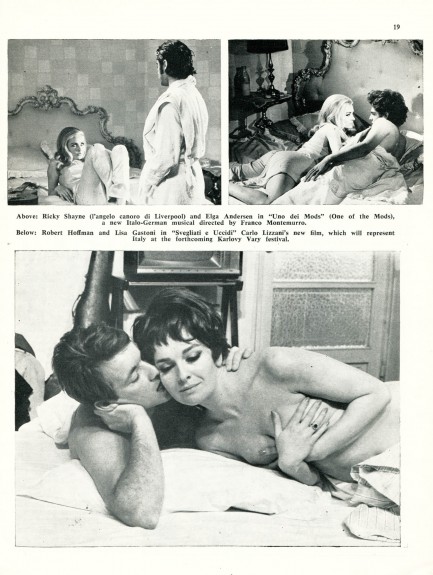

We’re showing you this August 1966 Continental Film Review for one reason—Raquel Welch. She appears in both the front and back of the magazine, and the latter photo was made while she was in the Canary Islands filming One Million Years B.C. That photo session featuring a blonde, windblown Welch was incredibly fruitful, at least if we’re to judge by the many different places we’ve seen frames from the shoot, including here, here, here and especially here. There had not been a sex symbol quite like Welch before, and in 1966 she had reached the apex of her allure, where she’d stay for quite a while. On the cover of the magazine are Christina Schollin and Jarl Kulle, pictured during a tender moment from the Swedish romantic comedy Änglar, finns dom? aka Love Mates. Inside you get features on the Berlin and San Sebastian film festivals, Sophia Loren, Nieves Navarro, Anita Ekberg, and more. CFR had launched in 1952, and now, fourteen years later, was one of Britain’s leading publications on foreign film. It was also a leading publication in showing nude actresses, and in fact by the 1970s was probably more noteworthy for its nudity than its journalism. The move probably undermined its credibility, but most magazines—whether fashion, film, or erotic—began showing more in the 1970s. CFR was simply following the trend, and reached its raciest level around 1973, as in the issue here. Fifteen scans below.

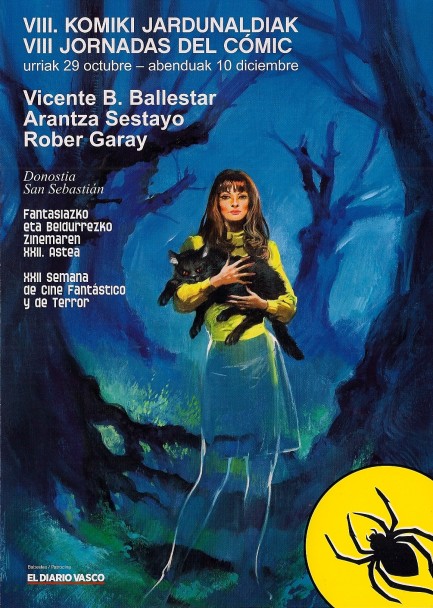

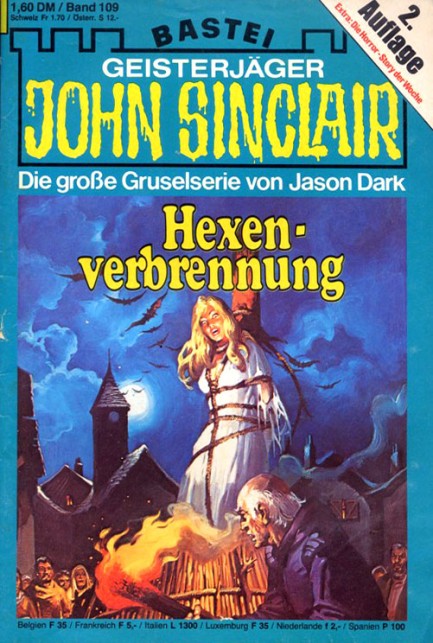

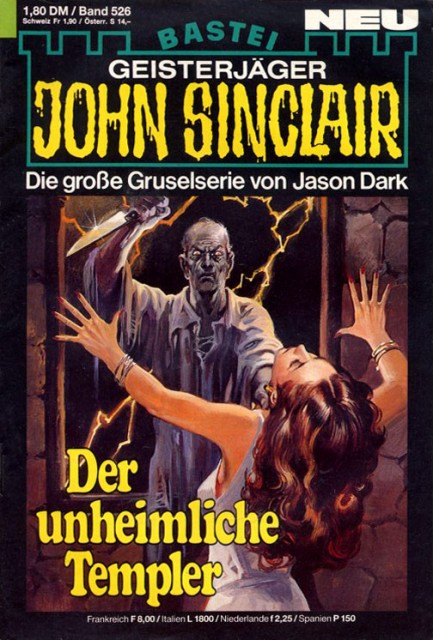

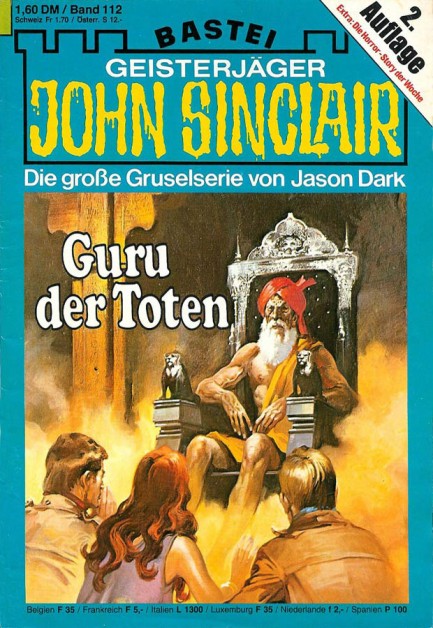

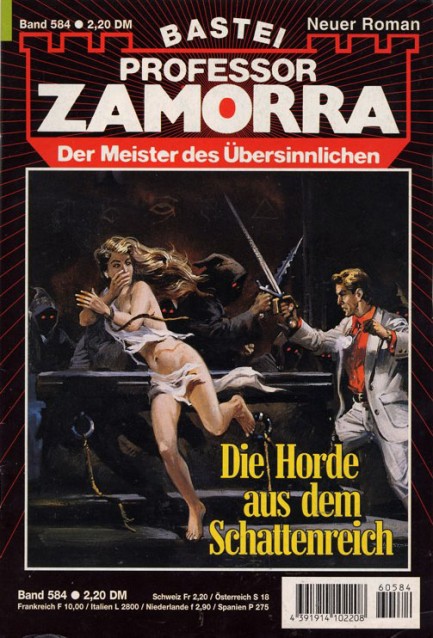

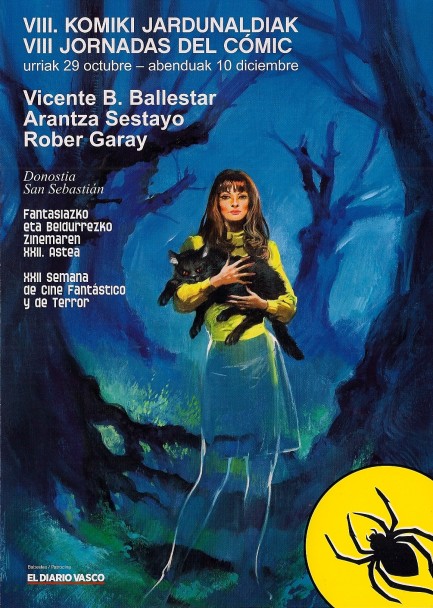

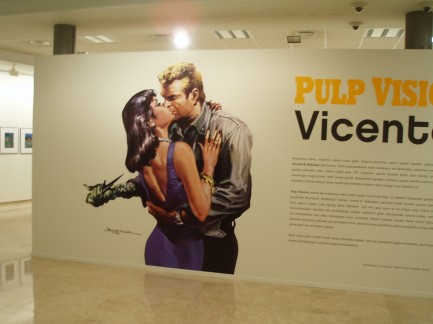

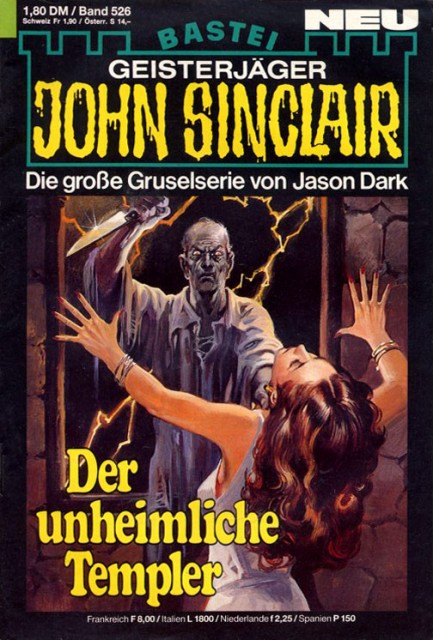

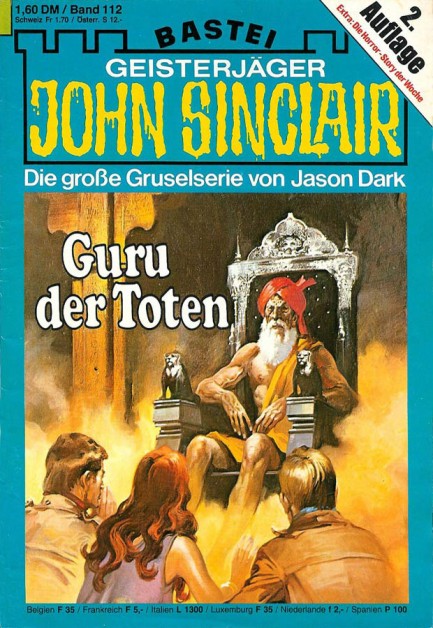

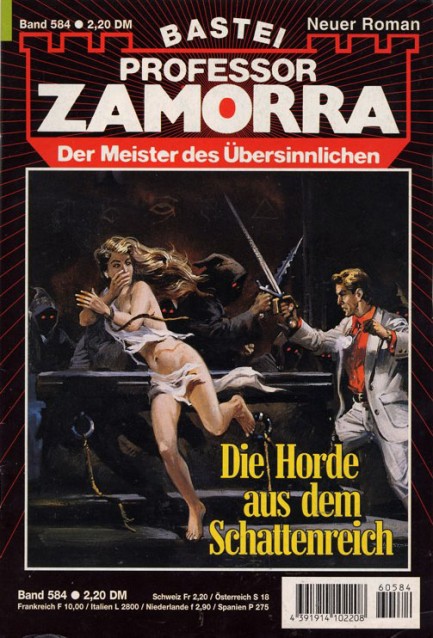

Veteran illustrator and instructor Vicente B. Ballestar’s pulp art makes the scene in Donostia-San Sebastian.

We love it when readers do some pulp digging for us, especially on a Friday. Here’s an e-mail we got last night from an acquaintance in Donostia-San Sebastian, Spain: Hola (P.S.G. Pumpometer). Here is some pulp you may like? This exhibit is at Casa Cultura Okendo, which you probably know is in Gros. The art is by Vicente B. Ballestar, a Catalan from Barcelona who painted many pulp covers. I thought the exhibit was quite interesting. There were at least 100 paintings. I have a scan and a few bad photos for you.

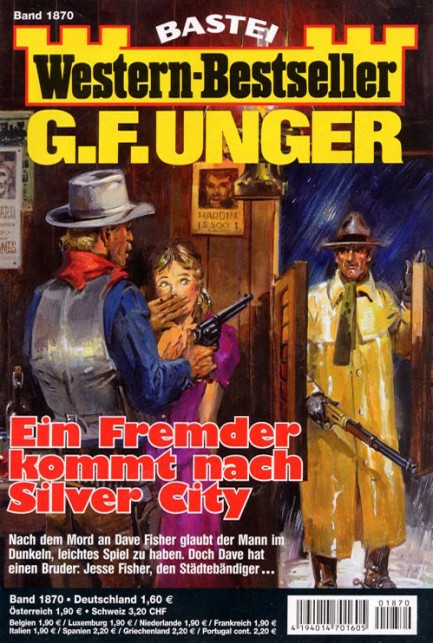

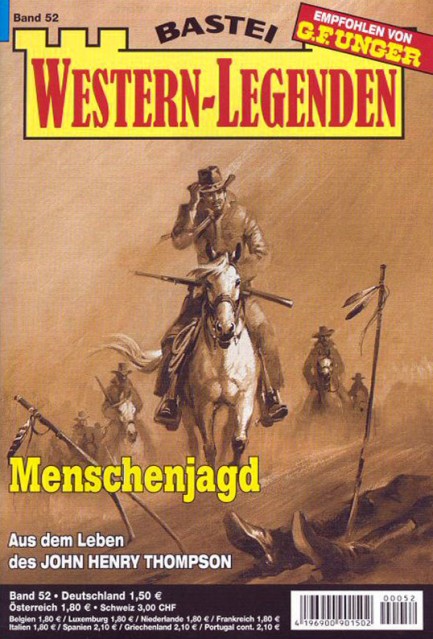

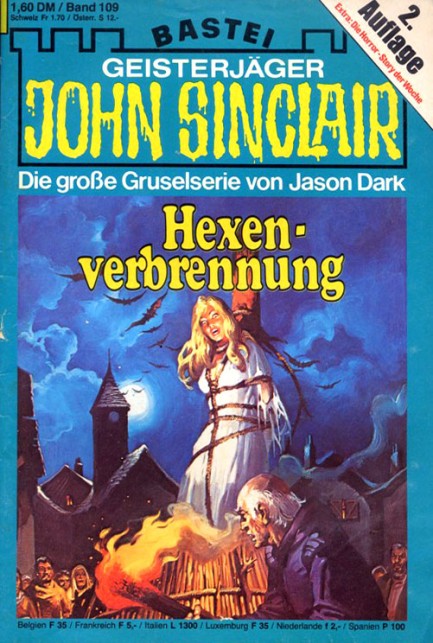

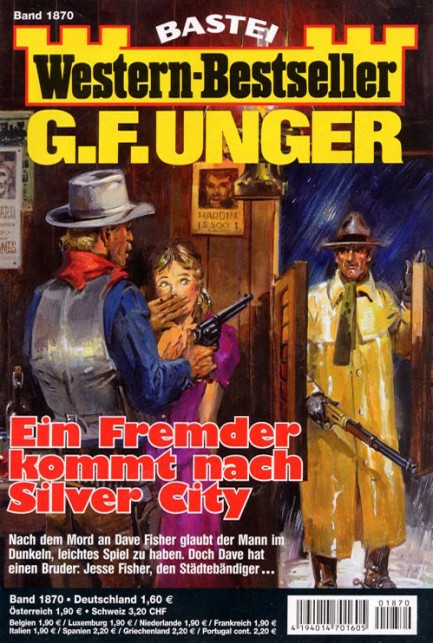

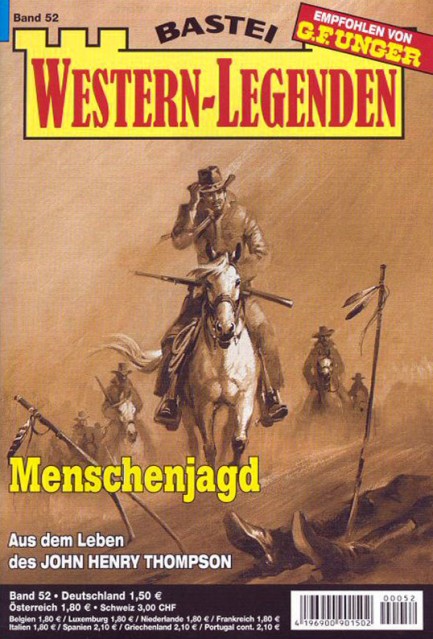

So now we’ll fill in the blanks for our friend (and thanks very much, by the way, for sending this to us). Vicente Ballestar was born in 1929, and worked primarily for the German publisher Bastion-Verlag, aka Bastei, where he created many of the often bizarre covers for the popular John Sinclair series. Later he went into fine art, the field in which he still works, and via his internationally published books about painting has become a renowned instructor of watercolor techniques. For someone who has worked steadily for such a long time, is widely read by art students, and has mounted exhibitions in places as far flung as Colombia and Italy, he has a rather minimal web presence. Even his blog is only two pages and hasn’t been updated for a year. But after a search we were able to find a few of his covers, and we’ve posted those below.

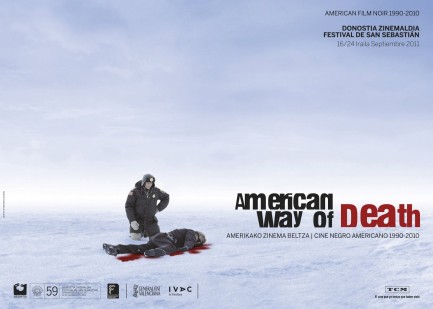

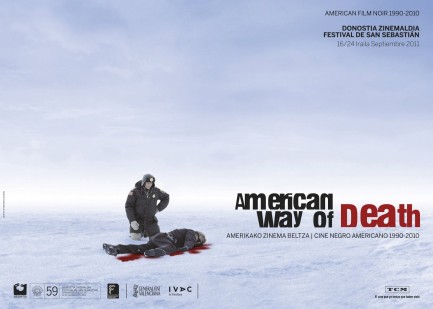

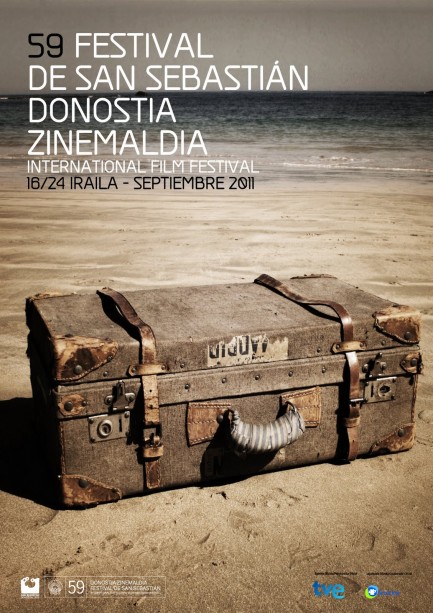

Donostia Zinemaldia examines life, death, and crime in America.

The Donostia Zinemaldia, aka San Sebastian Film Festival, is becoming one of the better fests in the world. Its 59th edition ended this weekend in Donostia-San Sebastian, Spain, and for the third year in a row we were there, though not for the festival per se. But we’re posting on it because it was thoroughly pulp-worthy due to the out-of-competition screenings of contemporary American crime films. The subset was called “The American Way of Death” and was restricted to films made within the last thirty years, including Goodfellas, Wild at Heart, Miller’s Crossing, King of New York, New Jack City, One False Move, Silence of the Lambs, Reservoir Dogs, Menace II Society, Red Rock West, Heat, Summer of Sam, Memento, Seven, Fargo, and twenty-five more. In fact, it must be one of the most comprehensive collections of American crime cinema ever screened, and the only significant film from the period they missed, in our opinion, was To Live and Die in L.A. As for the Festival itself, some of the stars who attended included Clive Owen, Antonio Banderas, and Glenn Close,  who received a lifetime achievement award. The top prize, called the Concha de Oro or Golden Shell, was won by Los Pasos Dobles—or The Double Steps—by Isaki Lacuesta, and Julie Delpy picked up a special prize for her new movie. If you ever find yourself in northern Spain in September, we recommend passing through Donostia-San Sebastian for the fest. You may not be able to get into the screenings, but the surfing, bars and events are just tremendous, so that should console you. who received a lifetime achievement award. The top prize, called the Concha de Oro or Golden Shell, was won by Los Pasos Dobles—or The Double Steps—by Isaki Lacuesta, and Julie Delpy picked up a special prize for her new movie. If you ever find yourself in northern Spain in September, we recommend passing through Donostia-San Sebastian for the fest. You may not be able to get into the screenings, but the surfing, bars and events are just tremendous, so that should console you.

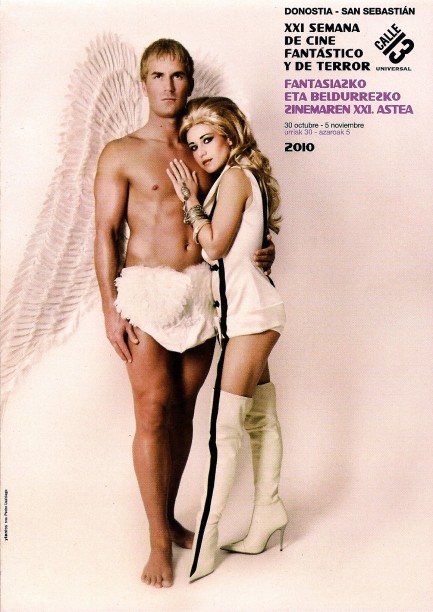

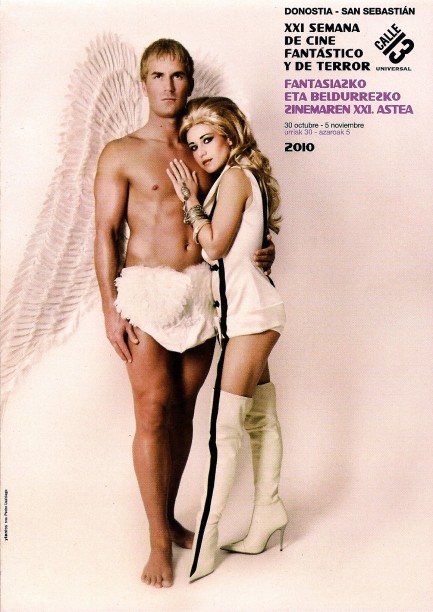

Basque film festival mines sci-fi classic for program cover.

The organizers of the Basque film festival Fantasiazko eta Beldurrezko Zinemaren XXI Astea, aka the Twenty-First Fantasy and Terror Film Festival, have borrowed a couple of iconic characters from the classic erotic space adventure Barbarella for their 2010 program. The two models above don’t look nearly as good as John Phillip Law and Jane Fonda did in 1968, but then again, who does? The festival starts today in Donostia-San Sebastian, Pais Vasco, Spain.

|

|

The headlines that mattered yesteryear.

2003—Hope Dies

Film legend Bob Hope dies of pneumonia two months after celebrating his 100th birthday. 1945—Churchill Given the Sack

In spite of admiring Winston Churchill as a great wartime leader, Britons elect

Clement Attlee the nation's new prime minister in a sweeping victory for the Labour Party over the Conservatives. 1952—Evita Peron Dies

Eva Duarte de Peron, aka Evita, wife of the president of the Argentine Republic, dies from cancer at age 33. Evita had brought the working classes into a position of political power never witnessed before, but was hated by the nation's powerful military class. She is lain to rest in Milan, Italy in a secret grave under a nun's name, but is eventually returned to Argentina for reburial beside her husband in 1974. 1943—Mussolini Calls It Quits

Italian dictator Benito Mussolini steps down as head of the armed forces and the government. It soon becomes clear that Il Duce did not relinquish power voluntarily, but was forced to resign after former Fascist colleagues turned against him. He is later installed by Germany as leader of the Italian Social Republic in the north of the country, but is killed by partisans in 1945.

|

|

|

It's easy. We have an uploader that makes it a snap. Use it to submit your art, text, header, and subhead. Your post can be funny, serious, or anything in between, as long as it's vintage pulp. You'll get a byline and experience the fleeting pride of free authorship. We'll edit your post for typos, but the rest is up to you. Click here to give us your best shot.

|

|

who received a lifetime achievement award. The top prize, called the Concha de Oro or Golden Shell, was won by Los Pasos Dobles—or The Double Steps—by Isaki Lacuesta, and Julie Delpy picked up a special prize for her new movie. If you ever find yourself in northern Spain in September, we recommend passing through Donostia-San Sebastian for the fest. You may not be able to get into the screenings, but the surfing, bars and events are just tremendous, so that should console you.

who received a lifetime achievement award. The top prize, called the Concha de Oro or Golden Shell, was won by Los Pasos Dobles—or The Double Steps—by Isaki Lacuesta, and Julie Delpy picked up a special prize for her new movie. If you ever find yourself in northern Spain in September, we recommend passing through Donostia-San Sebastian for the fest. You may not be able to get into the screenings, but the surfing, bars and events are just tremendous, so that should console you.