I can see the forest for the trees just fine. What I can't see is how you got us lost.

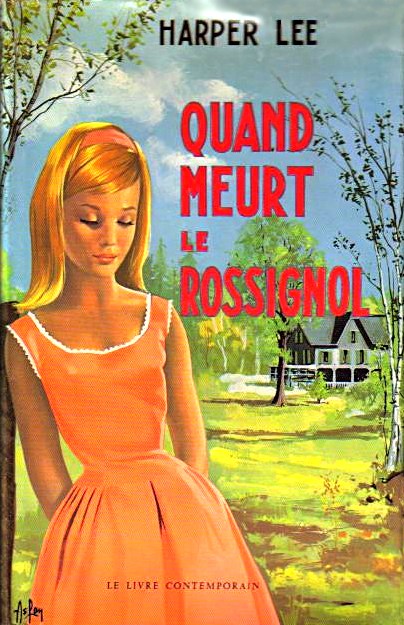

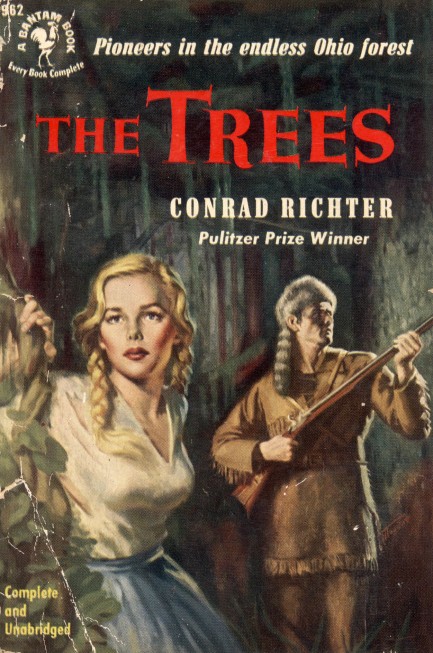

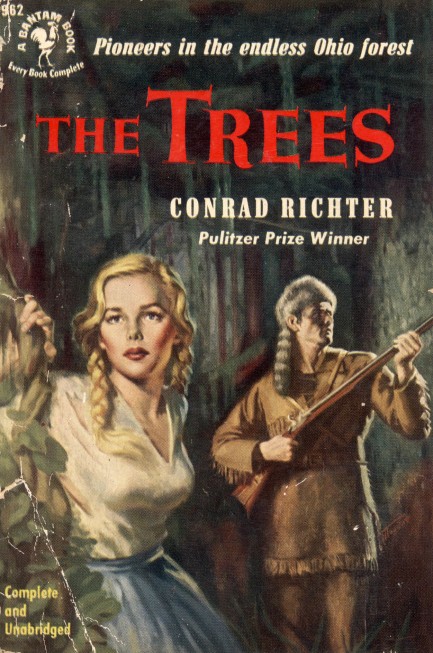

Above: Robert Maguire art for Conrad Richters's 1940 novel The Trees, which Bantam Books issued in this paperback edition in 1951. This was a serious novel, the first in an Ohio frontier trilogy known as The Awakening Land. The third novel, The Town, won Richter a Pulitzer Prize in 1951, which may have precipitated Bantam's pulpy re-issue. This isn't one we'll read, but we do like the art.

I walked home and sat on the stoop and watched the sun sink behind the trees and held the cat. It was a fine cat.

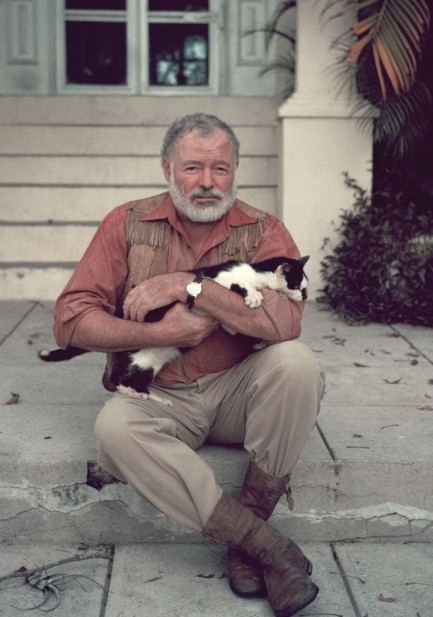

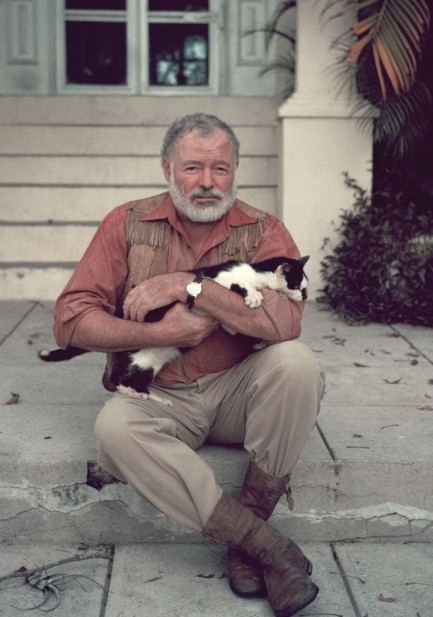

Above is one of the better photos of one of the better writers, Ernest Hemingway, seen here in 1954 at his house Finca de Vigía, which was located in San Francisco de Paula, Cuba. He owned the house and fifteen acre grounds from 1939 to 1960, and it was there that he wrote part of For Whom the Bell Tolls and all of his Pulitzer Prize-winning The Old Man and the Sea. The cat mostly walked across his typewriter keyboard.

The future is a dead Issue.

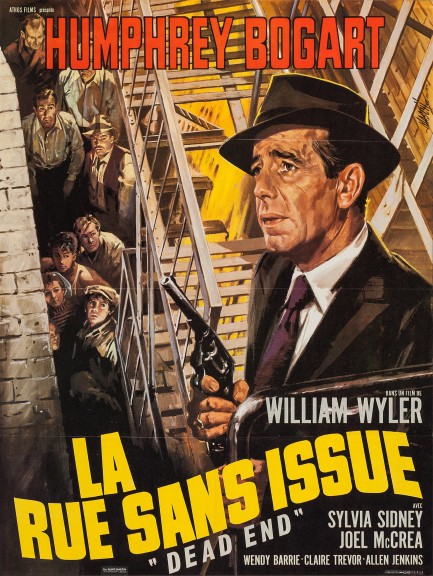

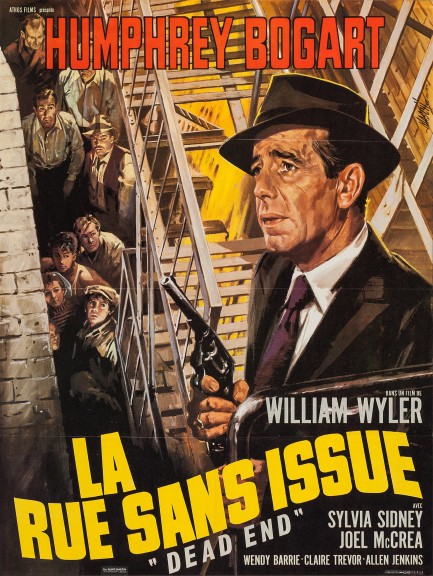

Once again we've chosen what we think is the best poster for a vintage film. In this case it's the urban drama Dead End with Humphrey Bogart, and the poster is one painted by Jean Mascii for the French release as La rue sans issue. Bogart features prominently in both the art and film, but the rest of cast includes Sylvia Sidney, Joel McCrea, Claire Trevor, and Wendy Barrie. We're talking good, solid actors—two of them future Academy Award winners—and they make Dead End an excellent movie. In addition it was based on a play by Sidney Kingsley, with the script penned by Lillian Hellman, more top talent. Kingsley had already won a Pulitzer Prize, and Hellman had written many hit plays. The plot of Dead End covers a day on a slummy dead end street in Manhattan on the East River, and the characters that interact there. The area is in the midst of gentrification, with fancy townhouses displacing longtime residents mired by the effects of the Great Depression. Because of construction on the next block the cosseted owners of a luxury home must for several days use their back entrance, which opens onto the dead end street. Thus you get interaction between all levels of society. There are the lowliest streets punks, an educated architect who can't find work, a woman who intends to marry for security instead of love, a gangster who's returned to his old neighborhood hoping to reconnect with his first love, and the rich man and his family.

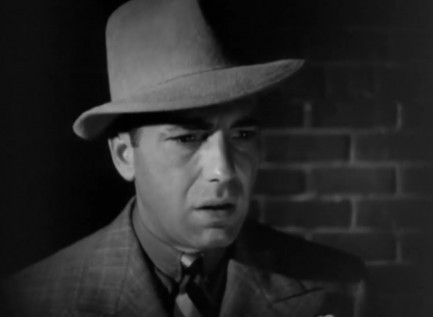

There's plenty going on in the film, but as always we like to keep our write-ups short, so for our purposes we'll focus on the gangster, Humphrey Bogart, and his former girl, Claire Trevor. Bogart has risen to the top ranks of crime through smarts and ruthlessness, but to him Trevor represents a cleaner past and possibly a better future. He waits on the street for a glimpse of her, and when that finally happens he's thrilled. Trevor is less so, but there's no doubt she still loves Bogie. When he says he'll take her away from the slum she balks. It soon dawns on Bogie that she doesn't intend to leave, and he's angry and confused. Trevor is evasive at first, then, pressured by Bogart, finally shouts, “I'm tired! I'm sick! Can't you see it! Look at me good! You're looking at me the way I used to be!” With that she moves from shadow:

Into light: Bogart takes a good look, from bottom to top:

And he realizes she is sick. Though it's unspoken, he realizes she has syphilis. All his dreams come crashing down in that devastating moment. He's disgusted, and it leads to an astonishing exchange of dialogue.

Bogart: Why didn't you get a job?

Trevor: They don't grow on trees.

Bogart: Why didn't you starve first?

Trevor: Why didn't you? Well? What did you expect?

Bogart escaped the poverty of that dead end street through organized crime, and killed on his rise to riches. Trevor had to survive through prostitution. Bogart thinks he's better than her; she tells him he's not. In his toxic male world, murder is less offensive than sex. He's the one who's twisted—not her. In addition to a great film moment, it's a clever Hays Code workaround. Nothing about sex, prostitution, or venereal disease could be stated, but through clever writing, acting, context, and direction—by William Wyler—the facts were clear to audiences. The rest of the story arcs are just as involving, and the movie on the whole is a mandatory drama. Dead End premiered in the U.S. in 1937, and in France today in 1938.

End of the line—Brando's place.

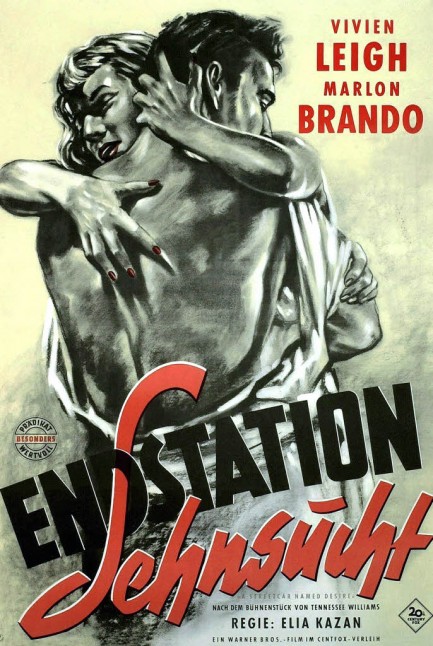

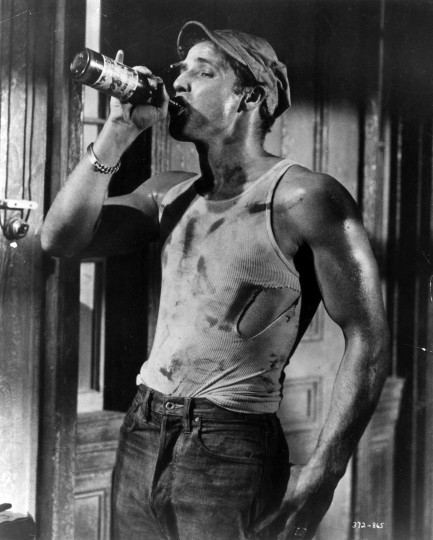

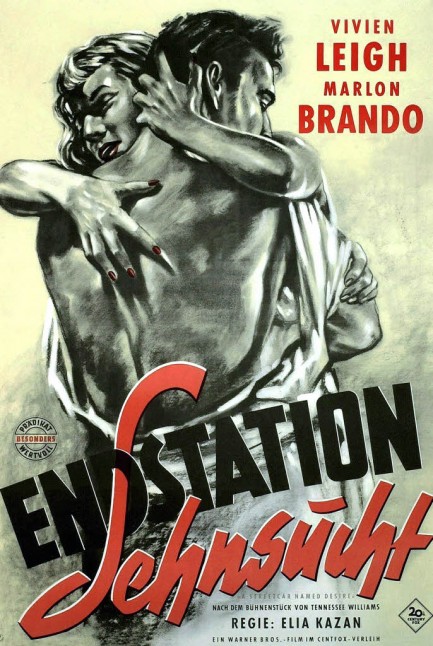

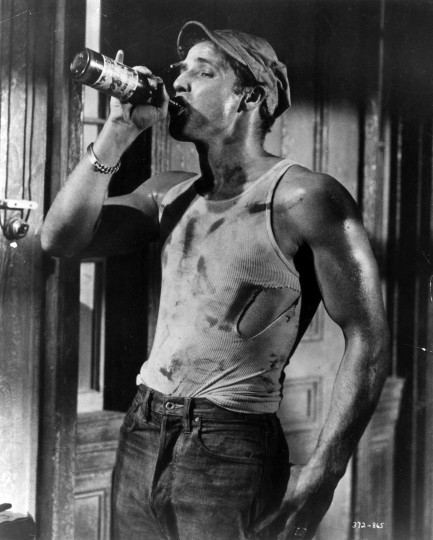

Above, a striking West German poster for Endstation Sehnsucht, which you know better as A Streetcar Named Desire. Admit it. You've heard of it, you know who Tennessee Williams is, but you haven't seen it (or seen or read the much racier Pulitzer Prize winning play it's based on). A famous critic once explained that a good book teaches you how to read it. The same can apply to movies. You have to let yourself be immersed in A Streetcar Named Desire. The first twenty minutes you might be tempted to give up. But once the dubious southern accents and style of the production settle into your head, you'll find a movie well worth watching, with a nice performance by Marlon Brando, who was comfortable in his role of the beefcakey Stanley Kowalski after having played it on Broadway. A Streetcar Named Desire is over the top—and over the needed running time, in the opinions of many—but it's an involving experience. After its U.S. premiere in September 1951 it rolled into West Germany as Endstation Sehnsucht today the same year.

Pair arrested in payoff scheme profess shock. “We were incredibly subtle about it,” claim jailbirds.

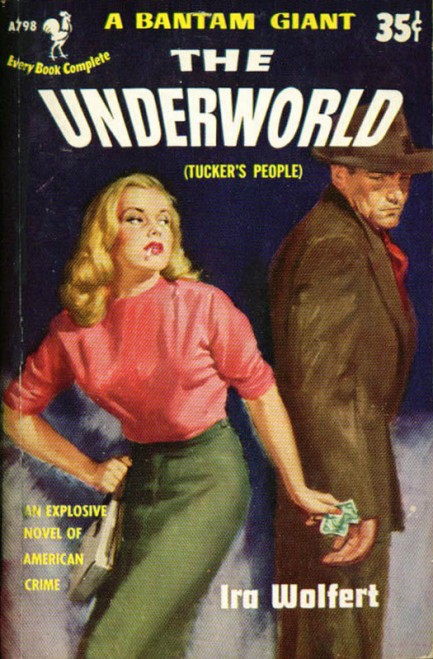

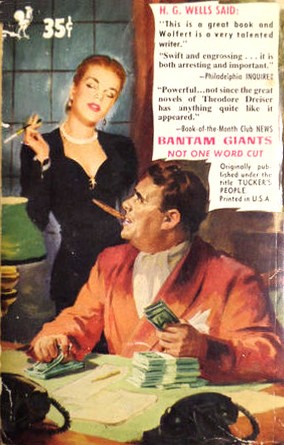

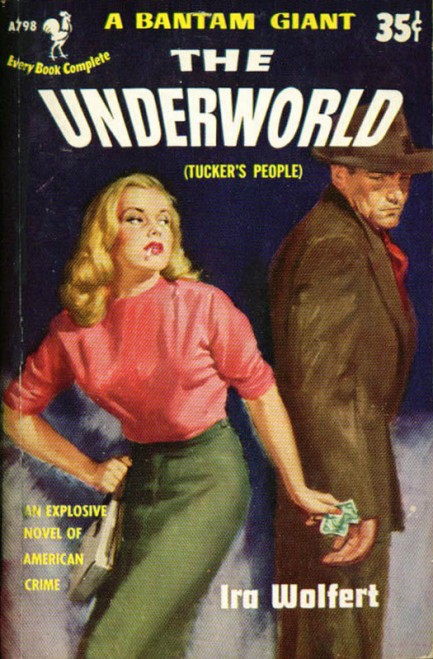

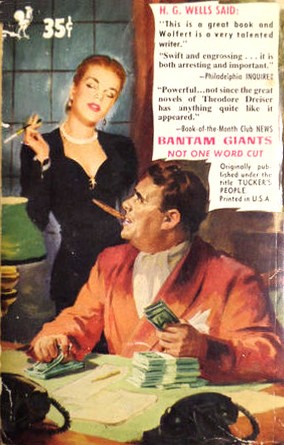

This cover for Ira Wolfert's The Underworld is uncredited, which is a shame considering it's wonderfully executed and wraps cleverly around to the rear of the book. Wolfert won a 1943 Pulitzer Prize for a series of articles about the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, aka the Battle of the Solomons, then the same year wrote Tucker's People, which was the original title of The Underworld. The Bantam paperback edition above was published in 1950. The book details the numbers rackets of New York City, which were executed far more subtly than the not very casual depiction in the art. The story captured Hollywood's attention and was produced as 1948's Force of Evil, starring John Garfield. We'll get around to talking about that movie a bit later. This cover for Ira Wolfert's The Underworld is uncredited, which is a shame considering it's wonderfully executed and wraps cleverly around to the rear of the book. Wolfert won a 1943 Pulitzer Prize for a series of articles about the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, aka the Battle of the Solomons, then the same year wrote Tucker's People, which was the original title of The Underworld. The Bantam paperback edition above was published in 1950. The book details the numbers rackets of New York City, which were executed far more subtly than the not very casual depiction in the art. The story captured Hollywood's attention and was produced as 1948's Force of Evil, starring John Garfield. We'll get around to talking about that movie a bit later.

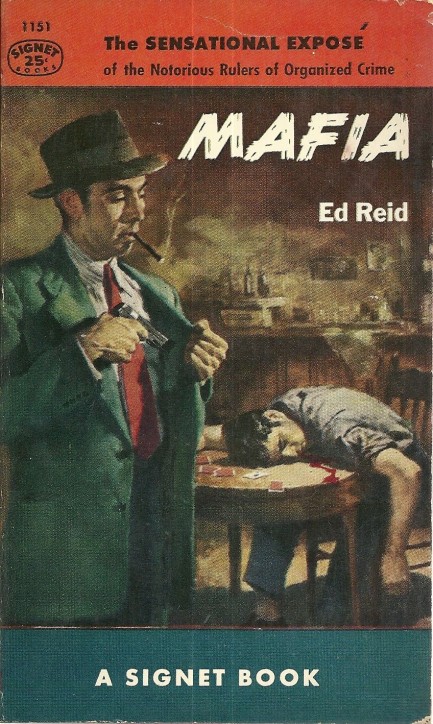

It ain't your lucky day anymore, is it, Mister "Oh-look-I-got another-straight-flush"?

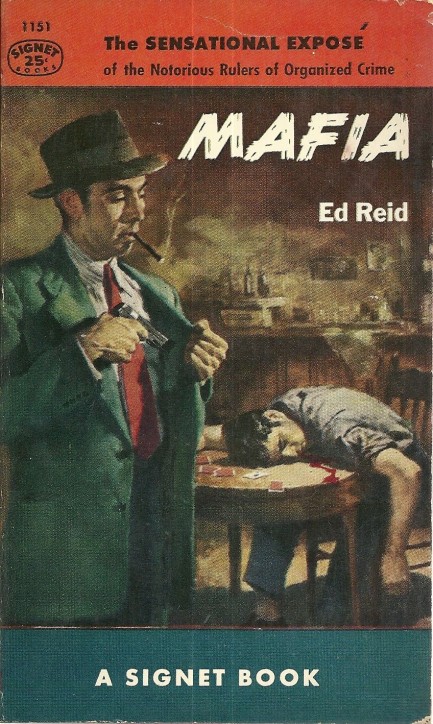

Mafia is a non-fiction rundown of the Italian organized crime rackets up to 1952, which is when the book first appeared in hardback. The above edition from Signet appeared in 1954. Author Ed Reid, who was an associate of organized crime crusader Charles Kefauver, covers cosa nostra personalities such as Vito Genovese, Lucky Luciano, the Fischetti Brothers, Albert Anastasia, and many others. Though non-fiction, Reid presents the information as a narrative, and we gather he took a bit of license. But he was a Pulitzer Prize winning reporter and Mafia was an eye-opener when it was published. Cover art is by James Avati, and serves as a reminder that the person with the pistol always has the best hand.

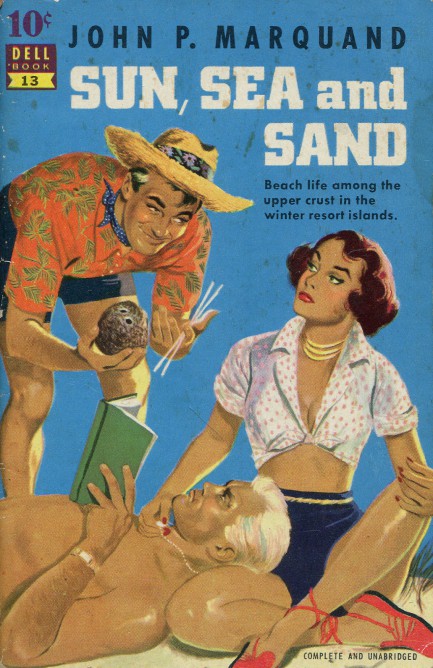

Coconut rum, ma'am? But I only brought two straws, so I'm afraid your husband will have to bugger off.

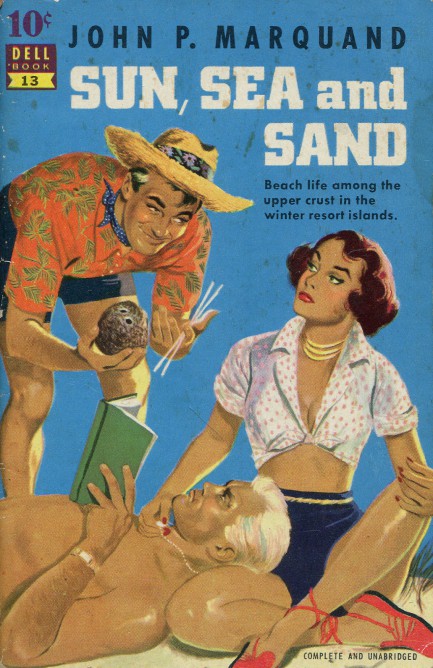

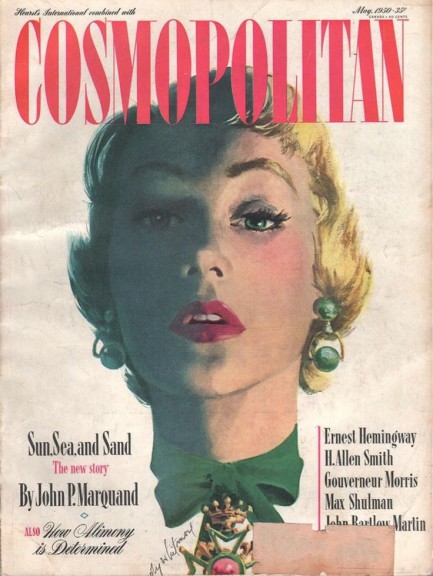

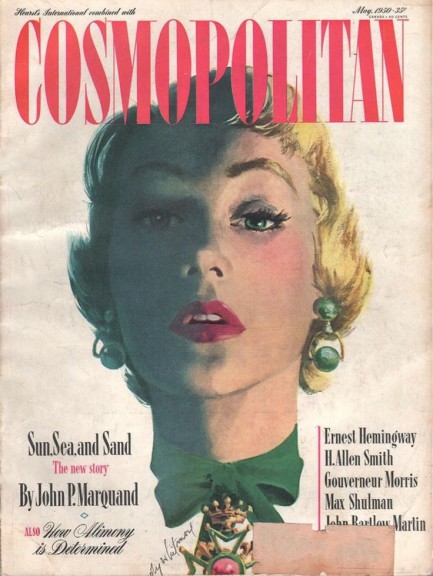

John P. Marquand won a 1938 Pulitzer Prize for The Late George Apley, so the above effort may seem a bit lightweight for him, but Marquand started out in genre fiction before becoming a leading literary figure. In his prime he specialized in satire of the upper classes, and Sun, Sea and Sand follows in that tradition, telling the tale of Epsom Felch, a problematic member of the snobbish Mulligatawny Club, which is located in the Bahamas. Epsom is a bit of a prankster, and the stuffy club membership are increasingly fed up with him, even though—as his main defender Spike constantly points out—pretty much every fun or memorable event that ever took place at the club was Epsom's  doing. Everything comes to a head at the annual Pirate Night ball. doing. Everything comes to a head at the annual Pirate Night ball. We really like Marquand. Always have. He's a funny and subtle writer, at least in his literary guise, and here you get that classic sense of the upper class cutting off its nose to spite its face, as club members conspire to boot a non-conformist though he's the only person bringing adventure and joy into their circle. Sun, Sea and Sand is novella length, and indeed its entirety first appeared in the May 1950 issue of Cosmopolitan, at right. The compact paperback edition, which is really little more than a pamphlet, comes from Dell, and the amusing cover art is by S.B. Jones.

Eddie Adams’ photograph inadvertently helped change public opinion about the Vietnam War.

Above, one of the most important photographic images of the twentieth century, a Pulitzer Prize winner shot by photographer Eddie Adams. On a sweltering Saigon afternoon, a Viet Cong officer is summarily executed by South Vietnamese national police chief Brig. Gen Nguyen Ngoc Loan, forty-two years ago today. There’s also a widely seen film of the gruesome incident. The photo galvanized the U.S. anti-war effort, but interestingly, Adams regretted taking it, saying that the circumstances around such a photo could never be adequately explained and Nguyen Ngoc Loan appeared to be a villain when perhaps he wasn’t. Such complex considerations are no longer a serious worry for war photographers. Due to Pentagon restrictions, it’s highly unlikely an image like this could now be captured.

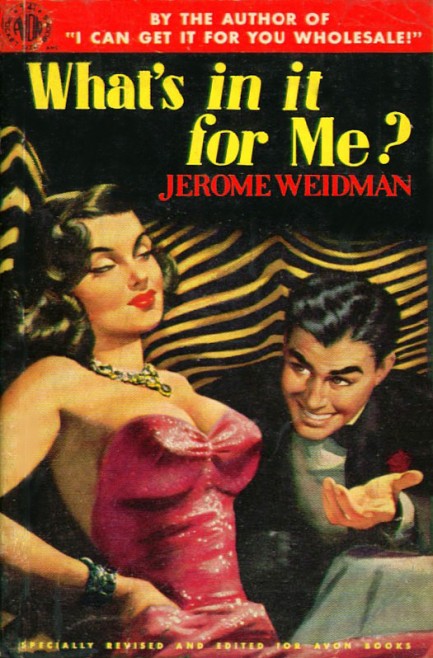

I assure you, mammary, my intentions are strictly honorable. Um... I said ma’am, right?

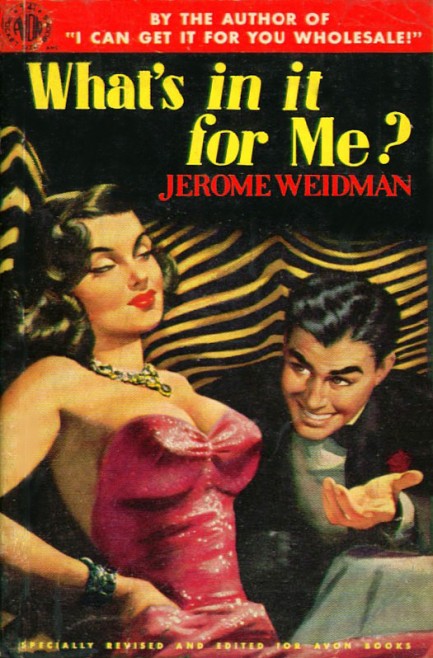

This is a brilliant cover for Jerome Weidman’s 1938 novel What’s in it for Me?, with its grinning sleazeball seeming to offer a free breast exam to a nubile young acquaintance. But the book was actually serious, depicting greed and amorality in New York City’s garment industry. Weidman went on to write the scathing Too Early To Tell about the Office of War Information, an American propaganda agency where he was employed during World War II, and then tackled the newspaper business with The Price Is Right. In Weidman’s fiction everything was a commodity to be bought, whether fabric or facts, and all humans were deficient. In 1960 he co-wrote a book of the popular musical Fiorello! about NYC mayor Fiorello Henry LaGuardia, and along with his collaborator won the Pulitzer Prize for drama. He drifted into a distinguished literary twilight, serving as president of the Author’s League of America, publishing his memoirs in 1986, and eventually passing in 1998. Though virtually unknown now, Weidman was an author in the class of John Updike or Ernest Hemingway. There are some bios of him on the Web, if you want ro know more.

The lullaby of birdland.

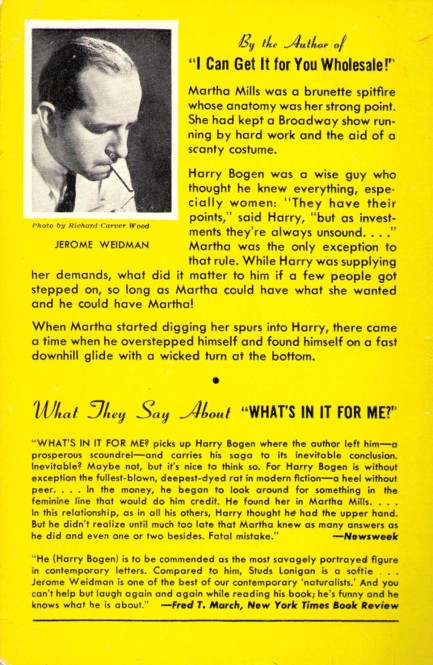

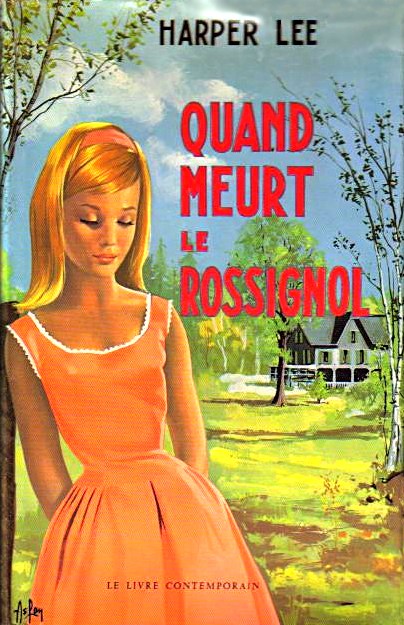

Harper Lee’s 1960 Pulitzer Prize winner To Kill a Mockingbird happens to be one of our favorite books. Actually, strike that. We think it’s one of the ten best American books ever written. So imagine our excitement when we found that the French hardback had been illustrated by Aslan, aka Alain Gourdon, one of the top artists of the pulp era. Interestingly, the title of the novel is slightly different in France. A rossignol is a nightingale, rather than a mockingbird. In French a mockingbird is a moquer, but that also means simply “to mock,” so that word would have given the title a slightly different meaning to the French. In any case, we love this cover.

|

|

The headlines that mattered yesteryear.

2003—Hope Dies

Film legend Bob Hope dies of pneumonia two months after celebrating his 100th birthday. 1945—Churchill Given the Sack

In spite of admiring Winston Churchill as a great wartime leader, Britons elect

Clement Attlee the nation's new prime minister in a sweeping victory for the Labour Party over the Conservatives. 1952—Evita Peron Dies

Eva Duarte de Peron, aka Evita, wife of the president of the Argentine Republic, dies from cancer at age 33. Evita had brought the working classes into a position of political power never witnessed before, but was hated by the nation's powerful military class. She is lain to rest in Milan, Italy in a secret grave under a nun's name, but is eventually returned to Argentina for reburial beside her husband in 1974. 1943—Mussolini Calls It Quits

Italian dictator Benito Mussolini steps down as head of the armed forces and the government. It soon becomes clear that Il Duce did not relinquish power voluntarily, but was forced to resign after former Fascist colleagues turned against him. He is later installed by Germany as leader of the Italian Social Republic in the north of the country, but is killed by partisans in 1945.

|

|

|

It's easy. We have an uploader that makes it a snap. Use it to submit your art, text, header, and subhead. Your post can be funny, serious, or anything in between, as long as it's vintage pulp. You'll get a byline and experience the fleeting pride of free authorship. We'll edit your post for typos, but the rest is up to you. Click here to give us your best shot.

|

|

This cover for Ira Wolfert's The Underworld is uncredited, which is a shame considering it's wonderfully executed and wraps cleverly around to the rear of the book. Wolfert won a 1943 Pulitzer Prize for a series of articles about the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, aka the Battle of the Solomons, then the same year wrote Tucker's People, which was the original title of The Underworld. The Bantam paperback edition above was published in 1950. The book details the numbers rackets of New York City, which were executed far more subtly than the not very casual depiction in the art. The story captured Hollywood's attention and was produced as 1948's Force of Evil, starring John Garfield. We'll get around to talking about that movie a bit later.

This cover for Ira Wolfert's The Underworld is uncredited, which is a shame considering it's wonderfully executed and wraps cleverly around to the rear of the book. Wolfert won a 1943 Pulitzer Prize for a series of articles about the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, aka the Battle of the Solomons, then the same year wrote Tucker's People, which was the original title of The Underworld. The Bantam paperback edition above was published in 1950. The book details the numbers rackets of New York City, which were executed far more subtly than the not very casual depiction in the art. The story captured Hollywood's attention and was produced as 1948's Force of Evil, starring John Garfield. We'll get around to talking about that movie a bit later.

doing. Everything comes to a head at the annual Pirate Night ball.

doing. Everything comes to a head at the annual Pirate Night ball.