*cough* This solo hike for reflection and solitude *cough cough* sure got ugly fast.

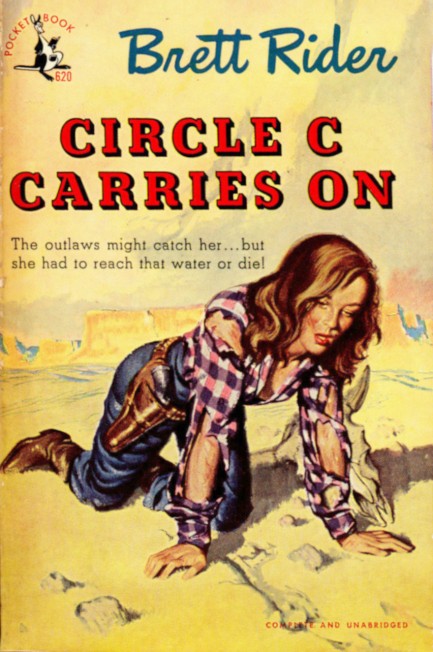

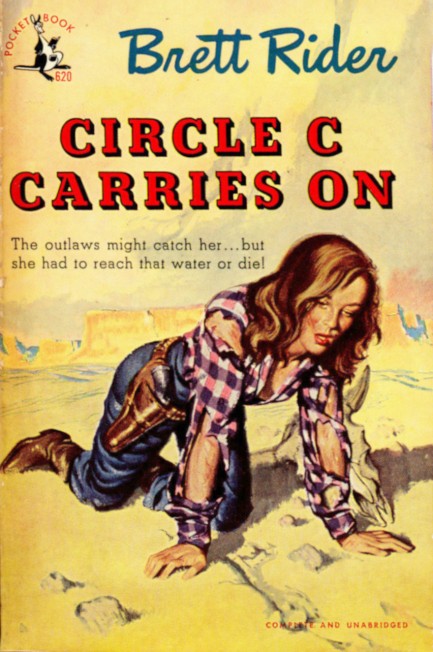

Above: a piece of Frank McCarthy art for Circle C Carries On by Brett Rider for Pocket Books, 1949. This is why we never go very far into the wilderness unless it's with a car, several other people, and beer.

Oh, it's a body. In my head I'd already blamed the weird smell around here on your dirty tennis shoes.

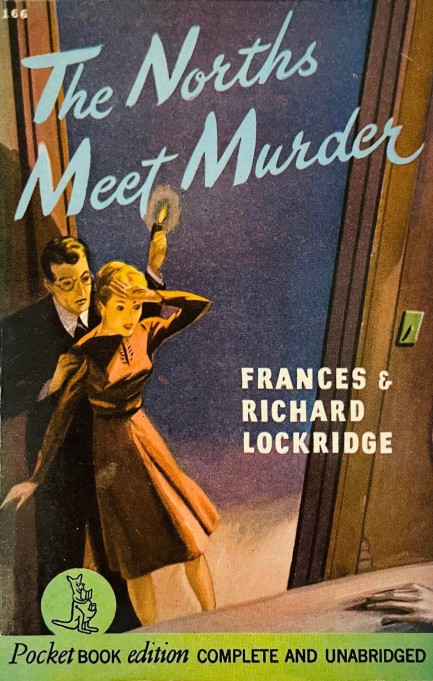

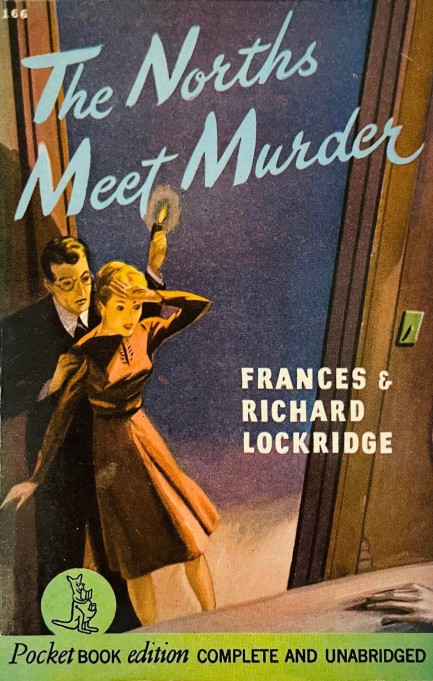

Originally published in 1940, the above Pocket Books edition of The Norths Meet Murder arrived in 1942. It was also published as Mr. & Mrs. North Meet Murder by Avon in 1958. The characters, Gerald and Pamela North, a Manhattan married couple who find themselves solving mysteries, had appeared in the New York Sun newspaper throughout the late 1930s, but The Norths Meet Murder is their first foray in novel form. We haven't read any of the others, but we own one, and we'll get to it. We've read a few mysteries featuring married sleuths. What's different here is that the authors Frances and Richard Lockridge write Pamela as an intuitive thinker whose leaps of logic—or illogic—leave her husband and the police scratching their heads. It could read as though she were a space case, but the Lockridges compensate for that by making her right most of the time. It's a winning formula in this tale that commences with Pamela deciding to throw a party in the empty apartment on the top floor of her building and discovering a corpse in the bathtub.

We were surprised that a detective named Weigand was the central character here, with the Norths serving in a supporting capacity. But that's just the Lockridges setting up the cop as a contact and pal for future novels, we suspect. By the end he was routinely enjoying cocktails with the Norths, though he initially suspected them of the murder. Pamela eventually figures out the solution about the same time as Wiegland, and it's clear she's gotten a taste for sleuthing. All very fun. In our view, for mystery fans The Norths Meet Murder is probably mandatory.

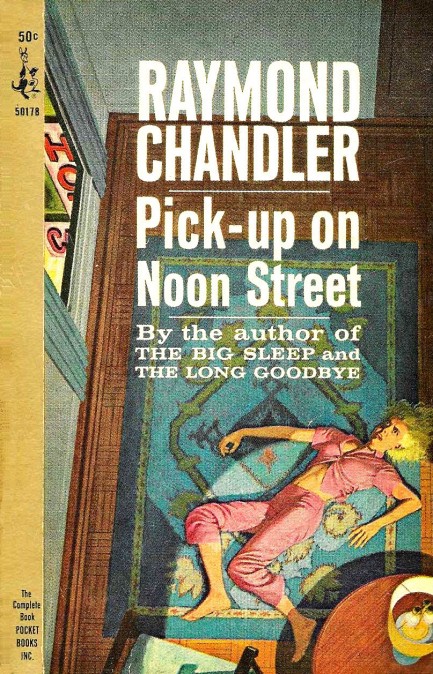

Yup. We remember being in this condition several times.

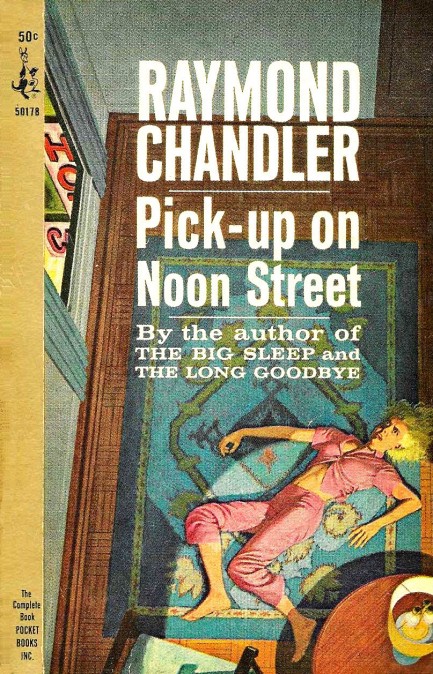

This piece of unusual and excellent cover art was painted for the 1965 Pocket Books edition of Raymond Chandler's four-part anthology Pick-Up on Noon Street, and the scene is personally familiar to us, though it's been years since we got so loaded we ended up insensate. But it happened a few times when we lived in Central America. Ever heard of a liquor called Tic Tack? Steer clear of that stuff. You'll end up a floor tile. The cover specifically illustrates the tale, “Guns at Cyrano's,” in which the hero finds an unconscious blonde in a hotel room. She didn't get that way by doing anything fun, though. The art was painted by Unknown, who's outdone himself here. Seriously, he's put together some masterpieces, but we think this one is top of the heap. You can read more about Pick-Up on Noon Street here.

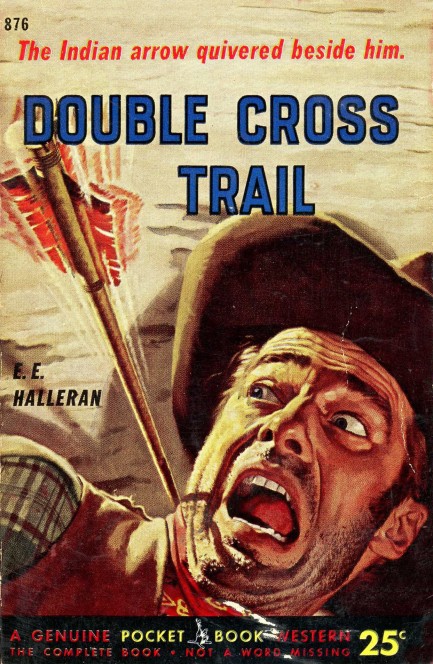

The thing about us cowboys, pardner, is we're tough, stoic, unflappa— Shiiiiit! Run!

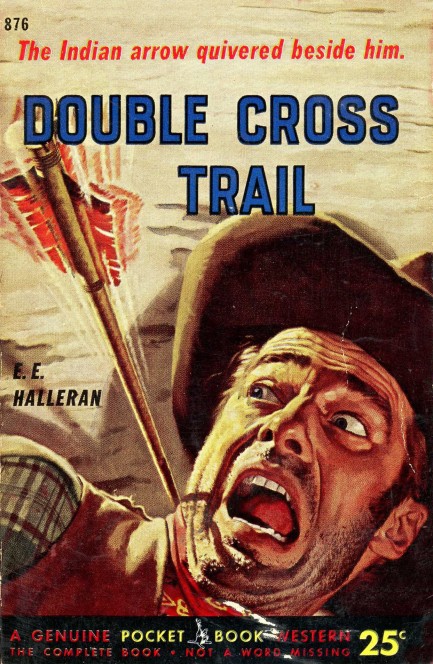

Vintage cowboys, as we said above, are usually tough and stoic, so we're going to guess the one on the cover of E.E. Halleran's Double Cross Trail isn't the main character. We've haven't read the book, so it's just a guess. But even when confronted with Cheyenne raiding parties, and even when fighting alongside the doomed George Armstrong Custer—which happens here—we bet the protagonist keeps his cool. We're firmly in the real history camp (as opposed to the patriotic mythology camp), however we've had good luck with westerns. None that we've read have had historical blinders on. A friend sent us an enjoyable one, Warren Kiefer's Outlaw, but as it's a 1989 book without pulpworthy cover art we won't highlight it. We're tempted to try Double Cross Trail but the stack of books is high, and the demands on our time are many. The amusing cover art here is by Stanley Borack, and this Pocket edition followed the novel's 1946 original publication in 1952.

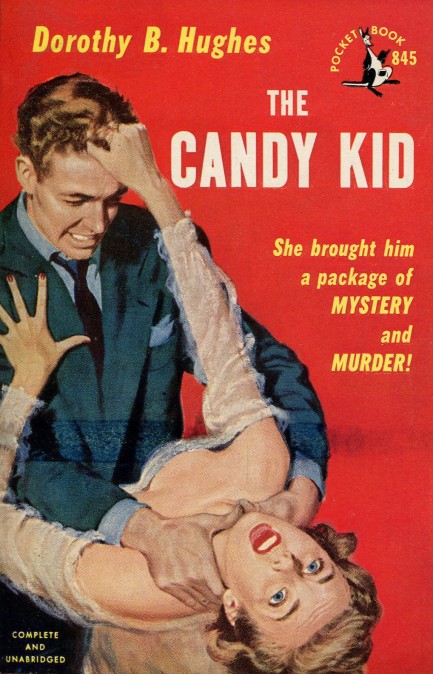

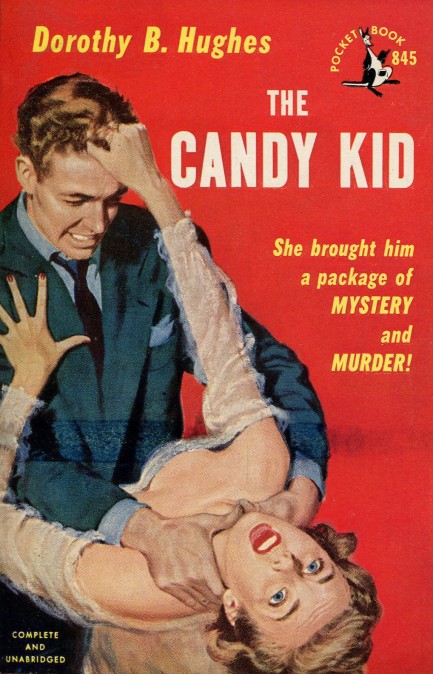

You knew those Reese's Cups were mine but you ate them anyway! Was it worth it? Well? Was it worth it?

This is a rarity on mid-century paperbacks—the strangler on Edward Vebell's cover for the 1951 thriller The Candy Kid is the protagonist. We almost never see one like this where the aggressive male isn't the villain, but it happens. In this case, he thinks the femme fatale has murdered his cousin. But he gets ahold of himself after a few seconds and gives her a chance to convince him that he's wrong. Telling you that isn't a spoiler, because the rear cover text reveals the murder anyway, and the hero's reaction isn't a turning point within the plot. He's pissed. But he gets over it.

The Candy Kid was written by the respected Dorothy B. Hughes, and she sticks close to the American southwest she explored in books such as 1946's Ride the Pink Horse. Here her main character, José “the Strangler” Aragon, is randomly selected on the streets of El Paso by upper class beauty Dulcinda “Sore Neck” Farrar to do a shady favor—take an envelope to across the border to Ciudad Juarez and exchange it for a package to be returned to her. She's chosen him because he looks like an itinerant laborer, like someone who needs, “un poco dinero.”

Actually, though, Aragon is a well-to-do rancher. He'd just gotten back from cowpunching when Dulcinda saw him, and he was sweaty and covered in grime. The whole thing was a joke to him. Based on her assumption, he'd pretended to be an immigrant day laborer, planning to reveal himself as a man of means to the pretty gringa later. But he takes more and more interest in this package business, and ends up performing the errand. Then the package is stolen from him.

What follows is a mystery involving a Greek crime kingpin, murder and revenge, twists and surprises, and unsolved crimes across the border. The odd title of the book comes from Dulcinda's name. Everyone calls her Dulcy, which in Spanish sounds like “dulce,” which means “sweet,” which causes one of the Mexican characters trying to remember her name to say, “that candy kid.” It's an involved journey. But then so is the tale.

We'll just come out and say it isn't Hughes' best, but she's always a fascinating author, particularly here, where she deftly captures the border atmosphere and attempts to portray a Mexican-American character who speaks Spanish and is comfortable on either side of the Rio Grande, yet is culturally distinct from his cousins down south. Some of those interactions have subtle class tensions that make them among the most interesting in the book. Other areas of the story are less successful. The biggest flaw is character motivation—Aragon has no compelling reason to get involved in Dulcy's troubles until his cousin dies, at the halfway mark. Following through on a prank just isn't enough. But you can't fault the level of technical skill on display, although Hughes writes in an unusual style filled with comma splices: It would have been funny, he was always the one who delayed the crowd, he knew everyone from Chihuahua to Mesa Verde. It works fine, which proves that if done just right an author can break any rule they want. Well, almost any rule. A crucial one for genre fiction is: make sure your protagonist really wants something. Even Hughes wasn't able to break that one and get away with it.

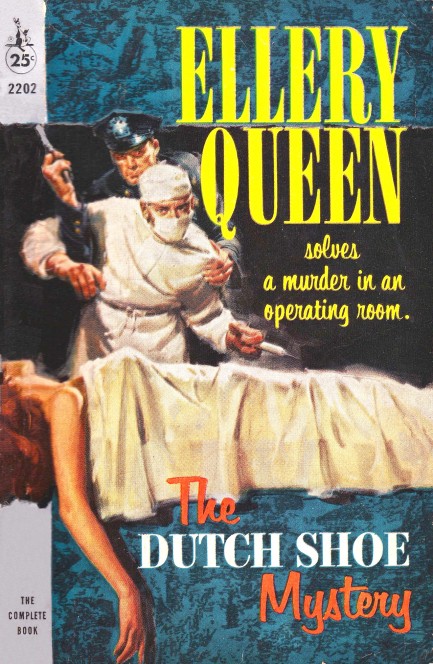

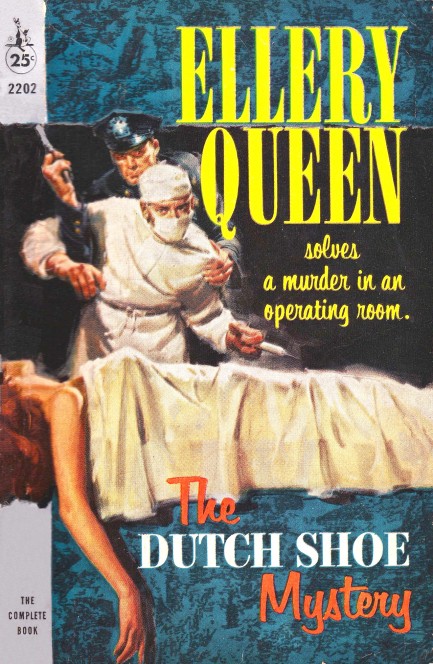

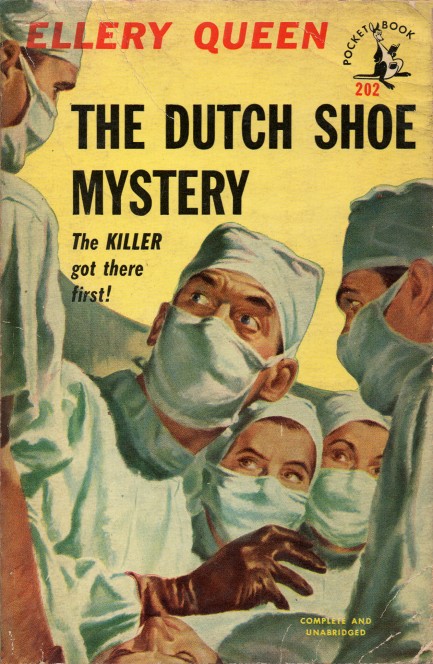

Let me go! I can save her! I just need a good nurse, a set of woodworking tools, and a shoehorn!

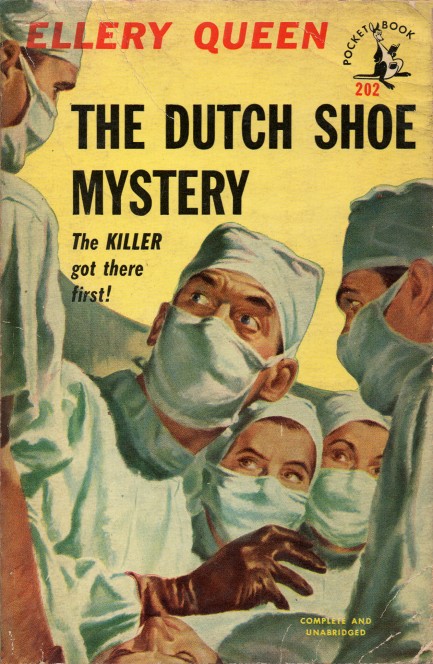

We already shared a 1952 Pocket Books cover for Ellery Queen's The Dutch Shoe Mystery, but this 1959 Pocket Books art by Jerry Allison goes a different direction, so we have a different, equally silly take on it. The Pulp Intl. girlfriends didn't get the joke last time, we suppose because they aren't old enough to know the same useless things we do, so we'll offer the reminder that a traditional Dutch shoe is made of wood and known as a clog. The Dutch Shoe Mystery features no clog that needs removal, just a ruptured gall bladder. Before the doctor can perform the operation, the patient, a millionairess who founded the hospital, is strangled with a piece of wire. Suspects: a few family members and the immediate medical staff. The “Dutch” in the title comes from the name of the hospital: Dutch Memorial. The “shoe” comes from the standard footwear of surgeons: white canvas moccasins which are the sole (oops) clue. Third in the Ellery Queen series, the authors Frederic Dannay and Manfred Bennington Lee (aka Daniel Nathan and Manford Lepofsky) basically update the classic locked room mystery by staging it in a medical facility. Good? Well, they published more than thirty subsequent Queen capers, so take that for what it's worth.

Lee needs a bit more practice before playing with the first team.

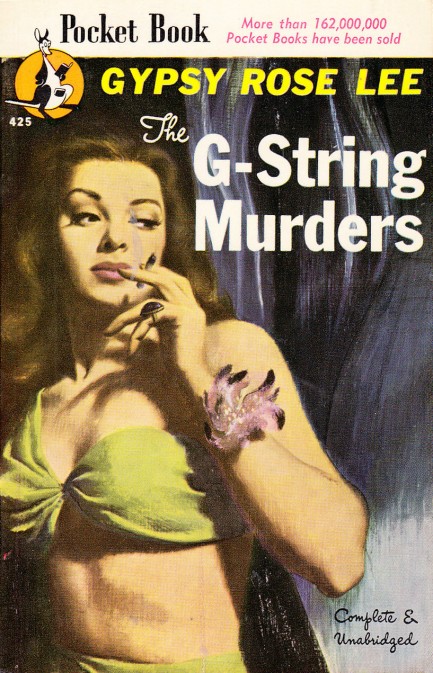

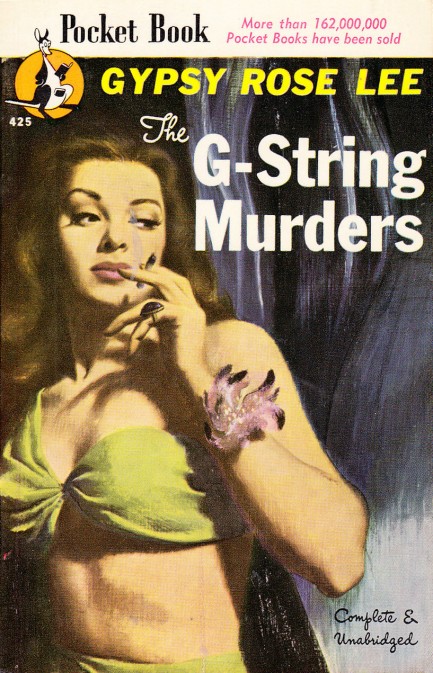

We couldn't have a pulp website and not get to this book eventually. Gypsy Rose Lee's 1941 novel The G-String Murders, for which you see an uncredited 1947 Pocket Books edition above, combines two major ingredients of pulp literature—murder and burlesque. Lee is both the author and main character, as setting-wise, a group of dancers and comedians work the stage at an NYC burlesque house called the Old Opera. In the midst of their relationships, jealousies, and petty squabbles, a dancer named Lolita la Verne turns up dead, strangled with a g-string. Since nobody liked her the suspects are numerous. The police are less than effective, so Lee and her boyfriend Biff take on the task of solving the murder, and eventually, a second.

There are some problems with the book. It's messy, undisciplined, meandering, and the first murder doesn't happen until a quarter of the way through the story. An excellent writer could pull off deferring the plot driver, but not Lee. That long deferral involves plenty of backstage burlesque atmosphere, but even there Lee comes up a little short. Val Munroe's Carnival of Passion, for example, really delves into the nuts and bolts of burlesque and does it in an engaging way. Considering the fact that Lee actually lived the life she should have done better with that part. Still it's a first novel, and better than many. We read somewhere that her second was good, so we're looking around for it. If we find it, we'll be talking about her as an author again.

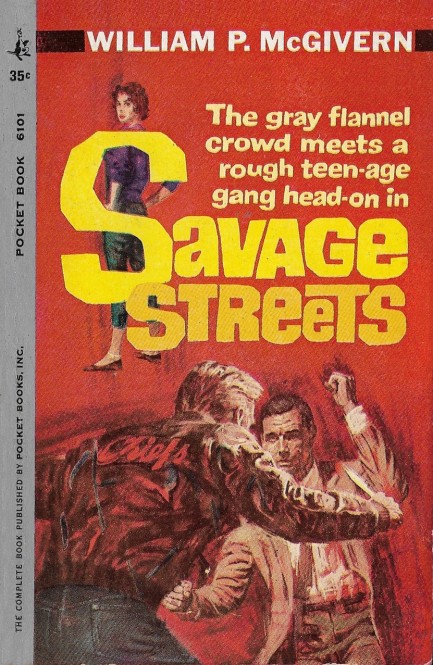

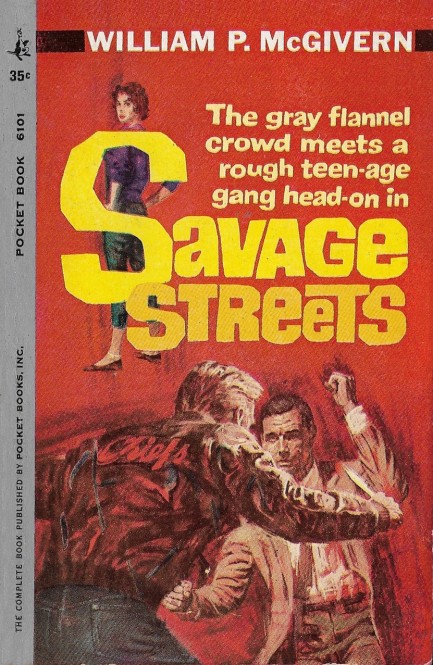

Okay, boomer, you may be young and tough, but this old guy's gonna give you a whipping you'll never forget.

William P. McGivern's 1961 novel Savage Streets was part of a wave of juvenile delinquent fiction characterized by the novels of Hal Elson and Harlan Ellison, and a nice example of a genre that rose in response to middle American fear and fascination with youth gangs. The narrative begins when some junior league thugs who call themselves the Chiefs begin extorting money from the pre-teen kids of a nearby suburb. The kids steal from their parents to satisfy these demands, but the thefts go unnoticed only for so long. The truth comes out, a suburban father intervenes with the gang on behalf of his son, and a fistfight results. Other parents in this conservative enclave are infuriated at the gang, and a group of them go to the police, but when the results aren't satisfactory they decide to deal with the Chiefs in a way the gang will understand—by hitting back twice as hard. From this point, McGivern takes his tale in an interesting direction. The dads expect the police to function as tools of their anger. Any attempt to give the Chiefs equal treatment or due process is met with outrage. In other words, they expect to be protected by the law without being accountable to it, while they expect the Chiefs to be accountable to the law without being protected by it. This leads not to resolution, but to increasing distrust, violence, and finally disaster upon disaster. Later the dads realize that the genesis of the crisis may not have been the Chiefs' extortion after all, but something the dads were involved with even earlier—a law they helped push through the city council. They might have realized the law was unfair, but none of them cared enough to bother looking closely at it. McGivern really hit pay dirt with this book. It's well written, immersive, and relevant.

Theories anyone? I mean, the x-ray told us there was a clog in the intestine, but it isn't even chewed. It's just weird.

Above: a cover for Ellery Queen's The Dutch Shoe Mystery originally published in 1931, with this Pocket paperback appearing in 1952. This is one of those deals where the author and lead character were presented to audiences as the same person, but the secret got out pretty quickly that Ellery Queen was actually two guys named Frederic Dannay and Manfred Bennington Lee, but those were pseudonyms too. Their real names were Daniel Nathan and Manford Lepofsky. Maybe they wrote mysteries because they loved to mindfuck people. And the title, as well, is a bit of a misdirection—the book has nothing to do with Dutch shoes at all.

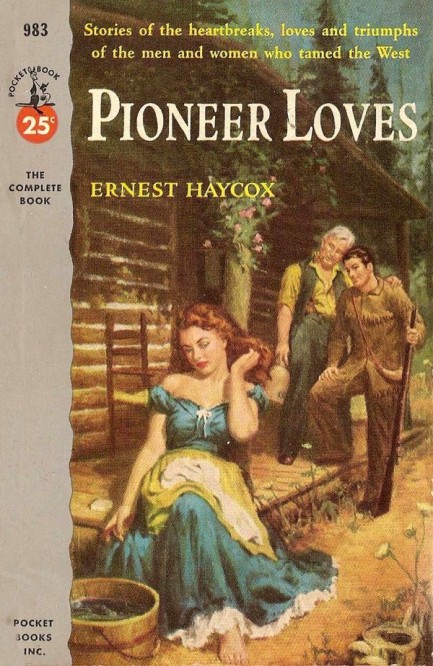

That bucket of water weighs thirty pounds but she handles it like a basket of muffins. Marry that girl, son. Household drudgery will be a breeze for her.

Ernest Haycox was a leading western and historical author. Above you see a cover for his 1954's short story collection Pioneer Loves. He died in 1950, with this appearing posthumously. We don't read many westerns, but by most accounts he was top level. We're featuring it today because the cover art by George Erickson fits a collection we put together last year. The group depicts rural women working hard while their men mostly stand by doing nothing. The Pulp Intl. girlfriends' reaction: “Typical!” Typical, eh? Who makes the seared duck with Pedro Ximénez sauce and mashed parsnips? That would be us. Who dispenses back rubs upon (daily) demand? Us again. Who handles panicked calls for humane evictions of spiders? That's right—us. Never let them diminish your worth, guys.

|

|

The headlines that mattered yesteryear.

2003—Hope Dies

Film legend Bob Hope dies of pneumonia two months after celebrating his 100th birthday. 1945—Churchill Given the Sack

In spite of admiring Winston Churchill as a great wartime leader, Britons elect

Clement Attlee the nation's new prime minister in a sweeping victory for the Labour Party over the Conservatives. 1952—Evita Peron Dies

Eva Duarte de Peron, aka Evita, wife of the president of the Argentine Republic, dies from cancer at age 33. Evita had brought the working classes into a position of political power never witnessed before, but was hated by the nation's powerful military class. She is lain to rest in Milan, Italy in a secret grave under a nun's name, but is eventually returned to Argentina for reburial beside her husband in 1974. 1943—Mussolini Calls It Quits

Italian dictator Benito Mussolini steps down as head of the armed forces and the government. It soon becomes clear that Il Duce did not relinquish power voluntarily, but was forced to resign after former Fascist colleagues turned against him. He is later installed by Germany as leader of the Italian Social Republic in the north of the country, but is killed by partisans in 1945.

|

|

|

It's easy. We have an uploader that makes it a snap. Use it to submit your art, text, header, and subhead. Your post can be funny, serious, or anything in between, as long as it's vintage pulp. You'll get a byline and experience the fleeting pride of free authorship. We'll edit your post for typos, but the rest is up to you. Click here to give us your best shot.

|

|