Mambo, rumba, merengue—you're great at them all. Have you by chance ever done a lap dance?

James Meese was responsible for this nice front for David C. Holmes' 1958 thriller The Velvet Ape. The art features the alpha pose we've highlighted before, where the main subject is straddled by a-shaped legs. Here, the woman dances in the foreground, the man observes from an easy chair, and a gun-wielding shadow creeps toward them beyond the background doorway. Is the woman in league with the shadow? Or are both man woman and man in big trouble? Whatever the answers, Meese has taken an oft used motif and produced a nice example of it. You can see our alpha collection here. The book tells the story of former naval aviator Buck Tankersley, who after disgrace and a lost career has fetched up in Panama, where he mainly drinks. When another aviator working for a company called Gulf Export takes a fatal header off a balcony into an empty pool, the local CIA chief, who's concerned about communist incursions in Central America, enlists Tankersley to apply for the dead flyer's vacancy and be eyes and ears inside the company. Tankersley soon meets Marley Kentner, sister of the dead aviator, who's looking for answers. Those answers, somehow or other, hinge upon a set of Indian ape dolls made from velvet, gourds, and monkey fur.

Overall, we'd say The Velvet Ape falls into the strictly average category. For one thing, the Panamanian setting isn't exploited as well as it could be. In fact, in an effort to establish that setting, Holmes mangles the first Spanish phrase he tries to use. That isn't entirely his fault. His editors were supposed to catch such errors. But it encapsulates the issues with the book, which feels a little lazy. Its plot is from the anti-commie handbook and its characters aren't compelling. But on the plus side, the climax involves Tankersley flying a Grumman Mallard seaplane directly into a hurricane. Points for that.

Wait, don't leave. I actually have a second talent, though I don't use it much. Let me just grab my banjo.

This cover for Josiah E. Greene's The Man with One Talent isn't anything special, but the title caught our eye because it's identical to that of an 1898 short story by Richard Harding Davis—who, speaking of talent, was an extraordinary war correspondent. The one talent referenced here by Greene is the capacity for violence, which the main character puts to use breaking up a union in a small New England town. This was originally published in hardback in 1951, with the Perma paperback coming the next year.

He can run from the past but he can't hide.

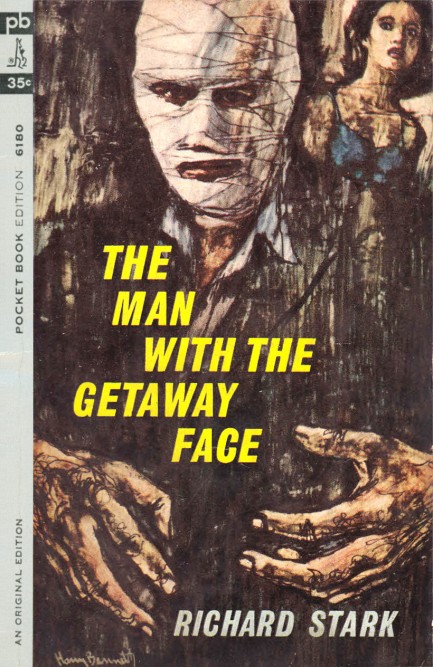

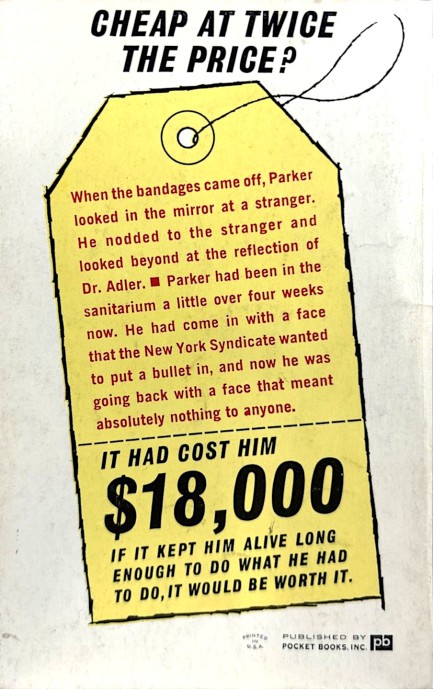

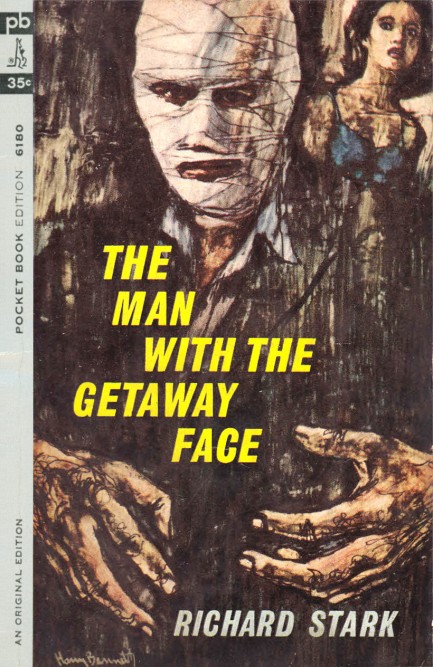

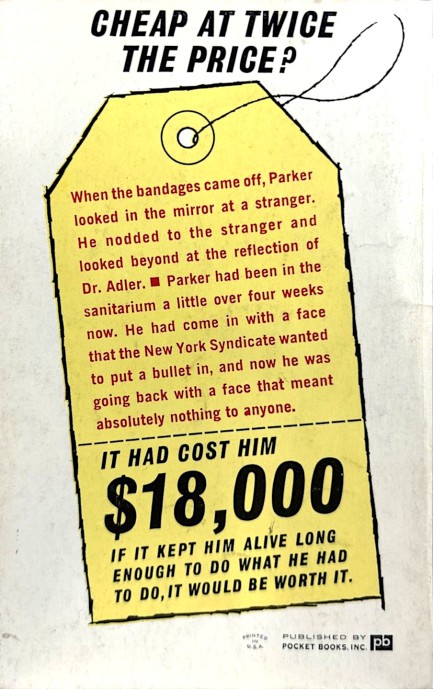

It took us a while but we've returned to Richard Stark, aka Donald E. Westlake, and his Parker series. We read entry one a few years ago. 1963's The Man with the Getaway Face is number two. The cover art here is by Harry Bennett and he basically copied his cover for book one, but changed the background and added the facial bandages. Those bandages reveal the premise—Parker has had a cosmetic surgeon change his face in order to help him evade “the Outfit,” who owe him in spades for various transgressions.

But Getaway Face doesn't focus on Parker's pursuers. Clearly, that's coming in the future. In the here and now he needs money, so he signs onto an armored car robbery, which, in adherence to the pulp law of tenuous connections turning into huge problems, boomerangs in such a way that his face doctor is murdered and Parker is blamed for it. His hands are full: deadly enemies, armed robbery, betrayal, murder, pursuit, and revenge. But he has very big hands. Nice work. We'll read book number three in the series soon.

He kills completely without reservation.

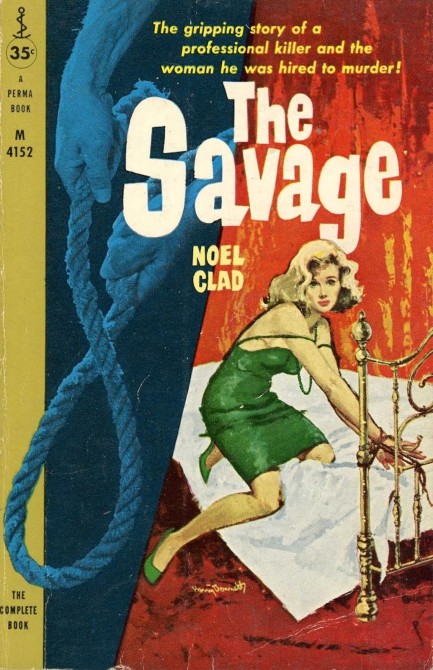

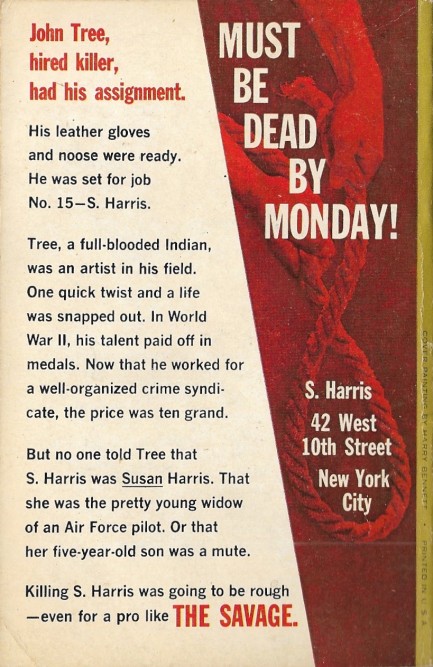

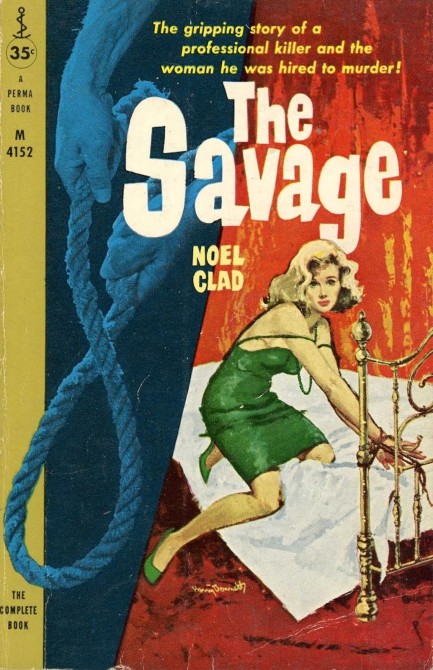

Noel Clad was a promising writer who died in a plane crash when he was thirty-seven. His novel The Savage shows some of that promise. It's about a professional killer named John Tree who's been summoned from his Wyoming ranch by the Chicago syndicate to go to New York City and dispose of an S. Harris. Like many fictional killers Tree has a code: he doesn't kill women. When he arrives in New York he learns that S. Harris is Susan Harris, which dismays him. Then the person who's bought the contract and is calling the shots tells Tree to rape Susan before killing her. Next he finds out she's a single mother with a mute five year-old son. None of it sits well with Tree, but it doesn't cause him to flip sides. He just wants out. He asks to be replaced on the job and be done with the situation. Out of sight, out of mind. His employers agree and send two replacement hired guns to do the job. Tree meets with them and realizes they have no ethics—they will rape their target, and they'll murder her son too.

There are hundreds if not thousands of regular mob hitmen in literature and cinema, so why not do something different? It shouldn't be a controversial idea, but sadly, so many these days consider it to be an assault on territory they own somehow. But diversification isn't a new thing. Clever writers have been doing it all along. Clad does it in The Savage. The killer for hire, the anti-hero John Tree, is full name John Running Tree, member of the Shoshone tribe, Native American by both blood and culture. That simple change takes the book in a different direction than other hitman tales. Here we have a killer who hates to think about his impoverished youth on a reservation, who glorifies Native American tests of manhood, and who sees a stripper wearing a tribal headdress as a prop and is angered. You get interesting passages like this:

Being here made him think of religion and how little he knew and the things that had passed for it when he was little: the spirits and the half-reverent amulets and charms. He remembered as he had not for years the lupine tea they drank for Manhood, remembered the girls on the Station eating mushrooms to see if my true love lies, and his own watching of wood smoke that twisted north when the hunting would be good. Even Tall Kite had no longer really believed in the thousand tribal spirits of the upland and the plain, the grass, the insects, the deer and the hawk. And God, in the Bureau of Indian Affairs, was no more than the price of chocolate milk. But in this hall, he had a pleasant feeling, relaxed, as though he was on a mountain all by himself.

1958 this was written, with loads of identity angst, as if it were published yesterday. John Running Tree moves like a folkloric wraith through New York City and tries to prevent Susan's defilement and death. The transgressiveness of the rape angle surprised us, as did the plot point that Tree kills by wire garrotte (not rope, as shown on the cover), but those added to the stakes of a harrowing and austere tale. Are there negatives? A few. Clad loses his tight control over the narrative from the moment Susan realizes—as she must—that Tree isn't just a nice guy hanging about for fun. Clad later forces the usage of Shoshone pictograms into a scene where the child mutely communicates an important clue. It might have worked under the right conditions, but in this case defied credulity. Other authorial errors accrue. Even so, good book. We'd read Clad again.

We'll talk more about how uncivilized you people are later. Right now I'm going to kill rare animals purely for ego.

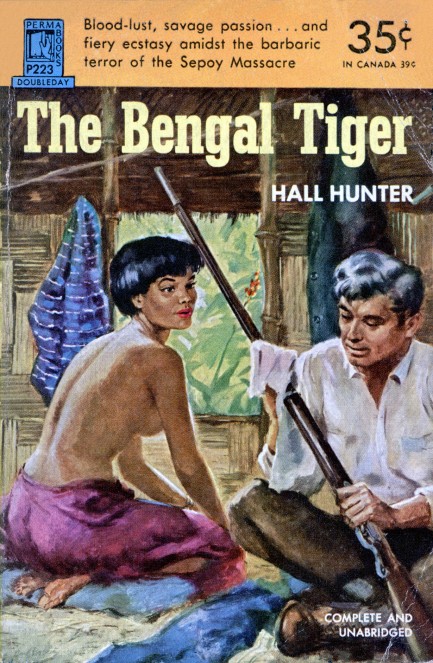

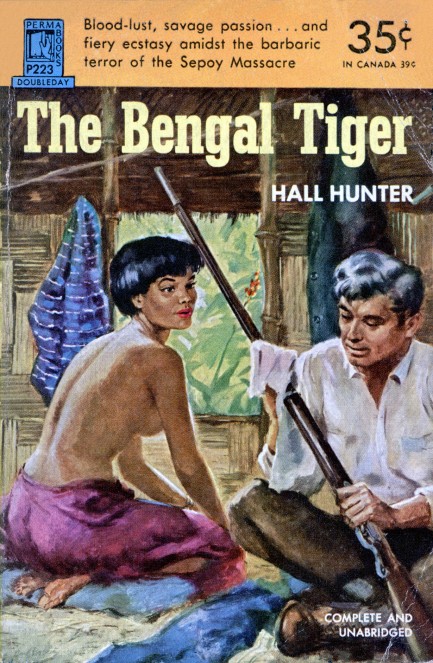

Above is a nice Carl Bobertz cover for Hall Hunter's, aka Edison Marshall's novel The Bengal Tiger, set in India during late 1850s. The lesson here is that he who prints the books establishes the narrative. The “barbaric terror of the Sepoy massacre” against England and its British East India Company caused about 2,400 British fatalities, according to official records of the time, but the toll is now thought to have been about 6,000. The Brits didn't bother to keep track of Indian deaths, but the change in recorded population between the previous census and the next indicated hundreds of thousands were killed. On a level orders of magnitude more disturbing is the fact that during the British occupation of India at least 40 million Indians, and possibly more than 100 million, were killed or starved to death.

If you were to ask Brits about the deadliness of their empire, most would not believe it, and many would try to excuse it. That's no surprise. Generally, the citizens of the expansionist powers can only deal with such horrors by first denying the truth, then if that fails, suggesting that there's a statute of limitations on mass murder. It happens, for example, whenever someone brings up slavery and westward expansion in the U.S. “It had nothing to do with me, or anyone else alive today.” However, over on the opposite side of reality where anti-Floridian concepts like factual history and mathematics reside, there are widely agreed upon studies revealing that—in Britain's case—$45 trillion in wealth was drained from India over about 170 years. That amount of gain has very much to do with everyone alive today, and in the future. Have a good Monday!

I asked if you had a request. Never playing piano again as long as I live doesn't count.

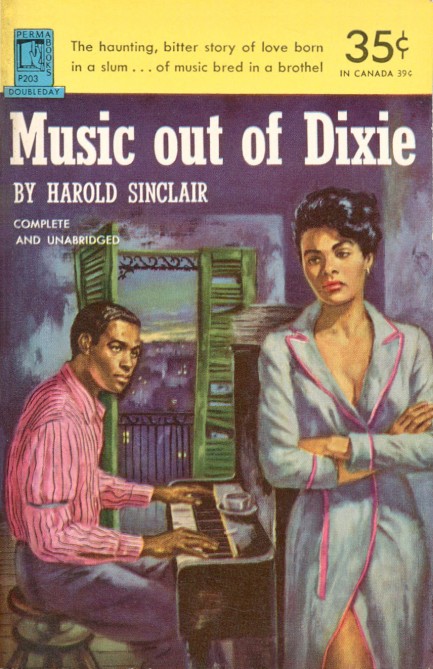

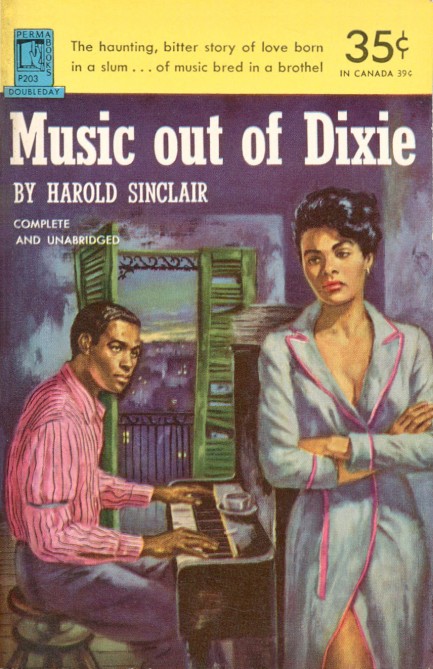

Above is a cover for Harold Sinclair's Music out of Dixie, 1952, from Perma Books. The cover art—which we left out of our recent collection of jazz covers for usage today—is by Owen Kampen, and looking at the moment he's captured, plus the city backdrop seen beyond the shutters, we think he's done excellent work. Don't let our juvenile little quip fool you—this is a well-written and serious book (you can tell it's serious before even opening it because it's more than twice as long as the average paperback) that follows fictional jazz legend Dade Tarrant from his impoverished childhood through his rise to musical significance. It's also pretty much the most New Orleans book you can ever hope to read. Sinclair leaves no stone unturned, from funeral processions to whorehouses, from the beflowered Garden District to dirty and dangerous Storyville, with multiple passes—of course—at Mardi Gras, and even choosing to make a minor character of real-life jazz legend Jelly Roll Morton.

Sinclair loves this subject matter, clearly, and he gets so much correct, for example the fact that “jazz” was a synonym for “jism” or “jizz.” He also explains how black jazz musicians were frozen out of early recording opportunities so that late arriving white musicians could copy the form and profit from it. The concept of recording music for money is so new at this point (the book mainly takes place around 1920) that the New Orleans trailblazers don't even realize what they're losing. There's an obvious irony in a white writer getting an early crack at describing and profiting from the most black of art forms, and it must have crossed Sinclair's mind when he described Tarrant wondering who the hell these white musicians were that he never saw in town even once but who were selling New Orleans jazz. Tarrant goes on to experience many of the ups and downs you'd expect, and though none of it's new, it's usually not written with such confidence and sense of place.

If there's a flaw here, it's his heavy-handed approach to black vernacular speech. Sinclair goes so far that the dialogue is sometimes a bit of a slog. Modern writers use a light touch with accents because they've learned that once you describe a character's ethnic or geographical background, with a word here or there readers will supply accents in their own heads. With a character from France, you don't have to write, “Zees musique ees vairy niiice.” The problem with Sinclair's approach is especially noticeable when white characters from New Orleans speak unaccented English, which isn't the case in real life. So there's cultural bias in the book, which will sometimes creep in even when an author writes of others respectfully. But it's still great work. The New York Times called it the “first novel to have been derived from the rich materials of New Orleans jazz.” The first ever? Hmm... well, we won't argue. Music out of Dixie is a recommended read.

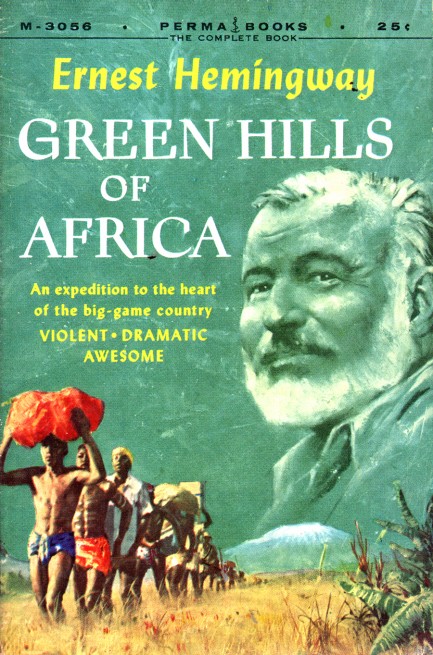

Hemingway scales the literary heights by plumbing human depths.

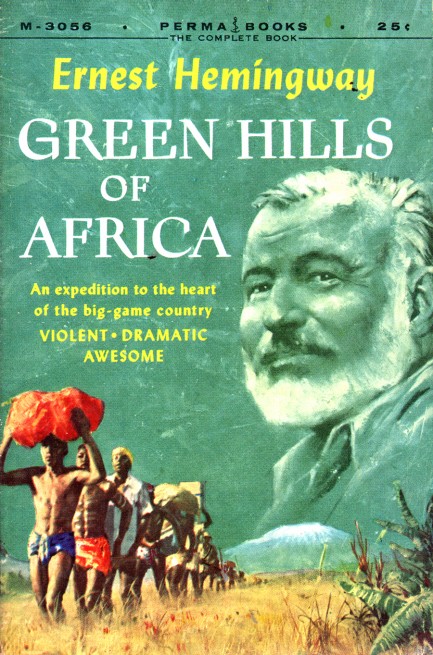

The great film director John Huston once made an interesting observation about Ernest Hemingway. He said Hemingway had fallen out of fashion because he wrote about courage. Huston didn't mean courage like Liam Neeson facing a pack of wolves or a terrorist. He meant the willingness to face temporality and mortality, and accept them for what they are. He meant the willingness to try to achieve things of great personal value while realizing none of them would last, and none of them truly mattered. The cultural trend has always been to tell people they're special and what they think and do matters and will last. But Hemingway considers that a conceit. 99.99999% of people are simply forgotten. The things they did are forgotten too.

This has happened to the most famous people of their eras. Name a U.S. governor who was in office during the Civil War. Name the wealthiest landowner of imperial Rome. They probably never imagined they'd be forgotten. Human temporality and mortality, set against the backdrop of nature or conflict, is Hemingway's thing. Nihilistic themes date from the earliest literature, but Hemingway, in projecting these ideas through a modern, almost pop culture lens, spoke for generations who had experienced two of the largest and deadliest wars in human history—we're talking well over 100 million dead. Hemingway was wounded in Italy in 1918. George Orwell was shot through the throat in Spain in 1937 during a precursor conflict to World War II. Erich Maria Remarque sustained multiple wounds in World War I. Imagine literature without them.

100 million war dead, among them writers who never wrote, painters who never painted, inventors who never invented. The world lost untold human capital, immeasurable progress. The literary public was ready for authors to tackle the senselessness of warfare. The between-wars period, encompassing a flu pandemic that killed 50 million, followed by the Great Depression, was likewise a wellspring of disillusionment. All these upheavals made clear that everything hangs by the barest thread. That level of suffering is unknown in the U.S. today, a country that has had its constant warfare sanitized for easy consumption, and that's really why Hemingway is out of favor—because his themes are almost alien to an American public that has forgotten what it means to suffer on a mass scale.

But while it's been fashionable for the last forty or so years to bash Hemingway, it's a self defeating exercise. We think what people usually mean to bash is his stature, or his out-of-date attitudes, which are understandable criticisms. However, to say he's a bad writer is to make oneself look ridiculous. We've said a few times before, and we'll say again here, that a good writer teaches you how to read their work. It's similar to the idea of willing suspension of disbelief in cinema. You accept the premise, or don't bother watching the film in the first place. It's okay to dislike a book as long as you try to read it on the terms the author asks. Otherwise, why bother? You read an adventure author on his or her terms, a mystery author on their terms, and a sleaze author on their terms. And certainly, you read a literary author on their terms.

None of this is to say Hemingway didn't have flaws, particularly when viewed trough a modern social lens. At Pulp, we tend to view writers as content producers first. For example, we pointed out recently that Camilo José Cela was a fascist. We personally are the opposite. But Cela still could write. Seeking enrichment only from ethically pure artists makes for a meager diet, and ethical purists should be forewarned—though modern judgments are necessary tools for measuring our progress, judgments come down the pike for everyone eventually. Legions of twenty-somethings who think they're pristine will one day be blamed for enabling slavery because they used smartphones dependent upon forced labor in African cobalt mines. Ethics evolve, and generational judgment comes for all.

Green Hills of Africa, originally published in 1935, with the Perma Books edition you see above coming in 1956 with Robert Schulz cover art, is autobiographical. A thirty-six year old Hemingway goes on safari mainly in Tanzania, and sets his personal goals against vast and indifferent wilds. By design nothing important seems to happen, but through his descriptive powers he brings Africa to the fore, and makes himself a bit player, just an ant on the endless landscape. The narrative could be shorter and more focused, but even as it rambles the same way Hemingway rambles across the dry plains, his wide ranging hunt for kudu, rhino, and lion assumes an almighty personal importance. His desire draws you in. His many small triumphs and failures become increasingly gripping, and sharpen the irony of his own impermanence and the impermanence of his acts.

But as we've mentioned before, Hemingway and his ilk operated under an earlier—and mistaken—ecological understanding. Our acts actually do matter, not because we're individually important, but in the accumulation of our billions of tiny effects. Hemingway assumed humans had no meaningful impact on nature. Now we know that's only half true—we're impossibly insignificant and incredibly impactful. We're tiny animalcules that have heedlessly wrecked a vast ecosystem. Green Hills of Africa is like a work of high fantasy, taking place in a reality that never truly existed. Despite its mistaken assumption, it does exactly what Hemingway wanted—says that nature is implacable, while human acts, achievements, and loves are comically impermanent. That was his message, a message people were ready to hear. That was Hemingway.

I'm pummeling you extra because I know when you tell the story later you'll say a man did it.

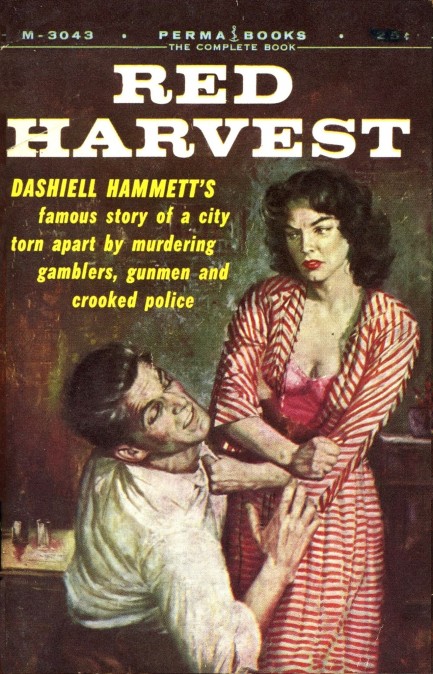

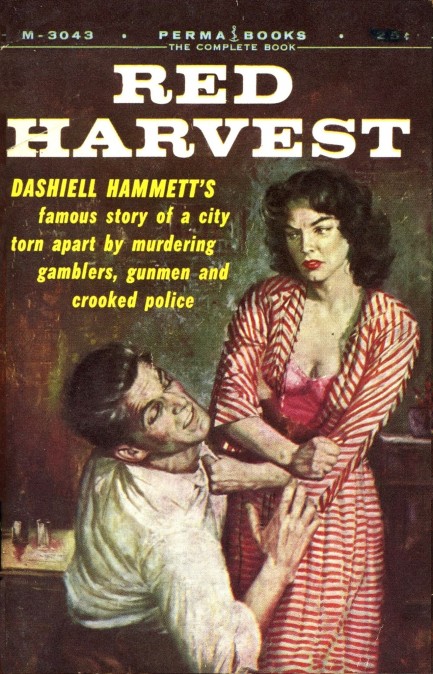

We already showed you a great 1958 Panther Books cover for Dashiell Hammett's 1929 debut novel Red Harvest. This cover comes from Perma and hit newsstands in 1956 with art by Lou Marchetti. We found it on Flickr. Hammett falls into that rare category of authors: a game changer. And this first book length effort from him is amazing. You can read a bit more about it here.

Now that you've shot the continent's last white rhino can we do something I think is romantic?

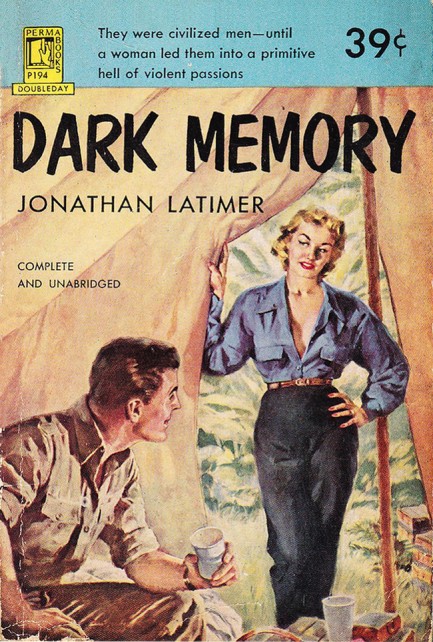

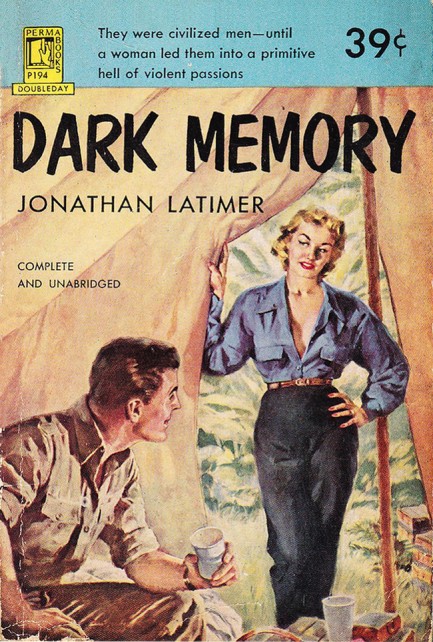

Jonathan Latimer's African adventure novel Dark Memory needs a more grandiose title, because it's pure Hemingway, and you know how lyrical his titles were. Latimer's novel is about nature, and courage, and women. It reads as if he said to himself after finishing Green Hills of Africa, “I wonder if I could do something like what Papa did here?” Well, he could. Dark Memory is a totally absorbing safari tale, a slice of time long gone. Latimer is in what we call the “trusted” category. He's set-and-forget. He's a concierge who's never failed a customer. If he wants to take us on an African safari, all we can say is, “Where do we get our malaria shots?”

Today people who hunt big game are excoriated on social media, and we understand why. The animals they shoot are simply too rare and valuable to be killed for ego. The hunters of yesteryear also killed for ego, but did so under a more limited ecological understanding and more lax political circumstances. Some practices of the past shouldn't survive, and killing lions for their skins shouldn't survive any more than should gladiatorial combat with swords. Big game hunters of today know that these African animals will be slaughtered unto extinction, but they simply don't care. Some might not want to shoot the last one, or hundredth one, or thousandth, but they're offset by sociopaths who'd pay a fortune to usher a species to oblivion. It's basic economics. The rarer the animal the more someone will pay to kill it.

If you were to search Dark Memory for good explanations why people kill African wildlife you'd be disappointed. Killing to prove one's own courage, killing a silverback gorilla carrying an infant, all seems shallow and pointless even to the main character, Jay Nichols, part of a group slogging through the wilds of Belgian Congo. When he later refers to the shooting—actually his shooting—of that female gorilla as a murder, his feelings are made crystal clear. In one scene another hunter explains how, during his current duties guiding a party of Brits, they've killed two hippos. For no reason except vanity. Then he lists the other casualties: “Zebra, eland, antelope, kuku, oryx, wildebeest, hartebeest, topi, [impala], waterbuck, dik-dik, oribi, bushbuck, reedbuck. I can't remember them all. Yes, and a number of different gazelles. We've killed more than two-hundred animals.”

Latimer is a show-not-tell type of writer, but seems to suggest that, while shooting a charging animal may prove a type of courage, it's of the crudest kind. The same rough men don't have enough courage to be truthful. Nor do they have the guts to be evenhanded—they must always weight the scales. Fairness angers them, because then they lose their advantages. But the book is only partly about all this. There's a woman on the expedition, Eve Salles, and her role barely differs from that of the animals. She's to be conquered for vanity too. In the context of this difficult trek through the Congolese jungle, she will be left in peace only if she belongs to someone. If the cruel, intimidating asshole running the safari has his druthers, it'll be him. She resists this depressing reality, but how long can she last?

Latimer tackles his themes declaratively, methodically, repetitively, and close to flawlessly. The man could definitely weave a tale, but for modern readers it'll be uncomfortable because he occasionally takes the route of racism in his descriptive passages. That's often true of vintage literature. We write—for a living even—so we never cut ourselves off from good writing. There's always something to learn. But those who read for pleasure should focus on the pleasure first. You have no other obligation, because there's plenty of good writing out there that doesn't equate gorillas and black men. But if, like the hunters in this book, you can trek past the hazards, your patience and forbearance will be rewarded—with high tension, savage action, deep reflection, and extraordinary visual power.

In the end, Dark Memory turns out to be a safari adventure that deftly channels the mid-century classics—Hemingway, Blixen, and others. Like those books, there's a level of dismissal toward the inhabitants of the land the characters claim to love, yet also like those books, there's insight into that rarefied realm of rich white Americans in the African wild. Latimer, a highly regarded crime writer, added big outdoor adventure to his résumé with Dark Memory, and as far as we're concerned he pulled it off. Originally published in 1940, the cover at top is from the 1953 Perma-Doubleday edition, painted by Carl Bobertz. It's actually a Canadian cover. We know only because every edition we've seen online has the price of 35¢, and a small notation that says: in Canada 39¢. Ours being 39¢, it must be Canadian. Brilliantly deduced, eh?

|

|

The headlines that mattered yesteryear.

2003—Hope Dies

Film legend Bob Hope dies of pneumonia two months after celebrating his 100th birthday. 1945—Churchill Given the Sack

In spite of admiring Winston Churchill as a great wartime leader, Britons elect

Clement Attlee the nation's new prime minister in a sweeping victory for the Labour Party over the Conservatives. 1952—Evita Peron Dies

Eva Duarte de Peron, aka Evita, wife of the president of the Argentine Republic, dies from cancer at age 33. Evita had brought the working classes into a position of political power never witnessed before, but was hated by the nation's powerful military class. She is lain to rest in Milan, Italy in a secret grave under a nun's name, but is eventually returned to Argentina for reburial beside her husband in 1974. 1943—Mussolini Calls It Quits

Italian dictator Benito Mussolini steps down as head of the armed forces and the government. It soon becomes clear that Il Duce did not relinquish power voluntarily, but was forced to resign after former Fascist colleagues turned against him. He is later installed by Germany as leader of the Italian Social Republic in the north of the country, but is killed by partisans in 1945.

|

|

|

It's easy. We have an uploader that makes it a snap. Use it to submit your art, text, header, and subhead. Your post can be funny, serious, or anything in between, as long as it's vintage pulp. You'll get a byline and experience the fleeting pride of free authorship. We'll edit your post for typos, but the rest is up to you. Click here to give us your best shot.

|

|