| Vintage Pulp | Nov 9 2015 |

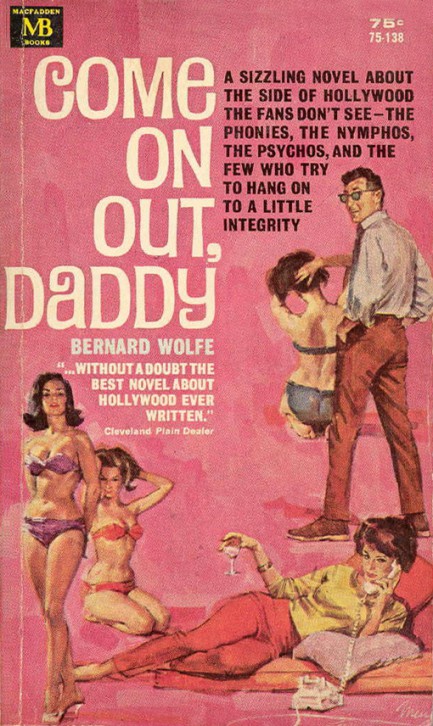

Bernard Wolfe is known for several reasons, not least of them for being Leon Trotsky’s personal secretary in Mexico City, but he was also a novelist of wide-ranging interests. Come On Out, Daddy was his Hollywood book, about a New York author who moves out west to cash in on an easy screenwriting job. While making a couple thousand dollars a week for doing very little he runs into the usual assortment of jaded Tinseltown characters—from big stars to little wannabes—and trysts with an assortment of disposable beauties before of course meeting the woman of his dreams. It’s episodic due to it being partly cobbled together from short stories published in Playboy and Cavalier, but reasonably well regarded as a cultural satire. Life described it as “garrulously and surrealistically told by a huge cast of people in varying stages of corruption.” 1963 on the hardback, and 1964 on the above, with cool cover art by James Meese.

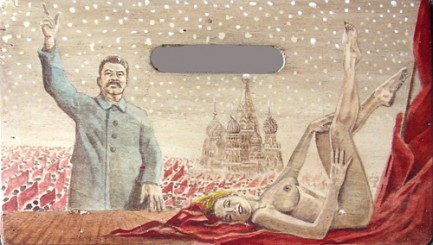

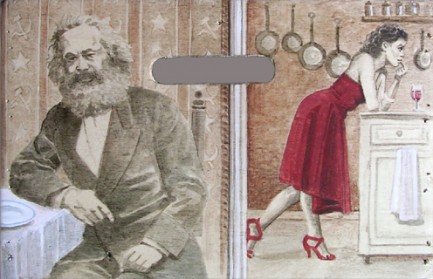

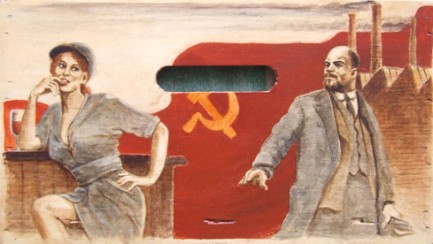

| Modern Pulp | Mar 16 2013 |

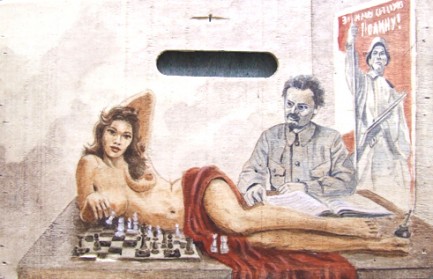

Last year we shared some unusual pulp influenced crate paintings from a French artist named Jacques Puiseux, and this morning we received more scans of his Marxist themed pieces via email. Last time we shared Puiseux’s work, we mentioned that we avoid posting modern art, and that’s true, but we didn’t want to leave you with the impression that we find it inferior to vintage art (if that were true we wouldn't bother to have a "Modern Pulp" category on the website). What we find inferior is modern promotional art—e.g., book covers, movie posters and the like. And obviously we find modern movies inferior, but then who doesn’t? However modern fine art is something we very much like, and more to the point, we like the relationship it has to the viewer. We aren’t art majors or anything, so bear with us while we try to explain ourselves.

| Intl. Notebook | Oct 27 2010 |

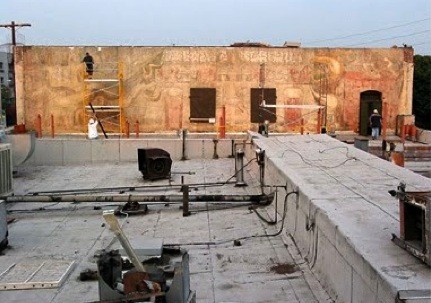

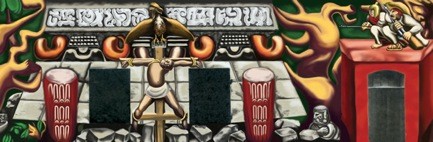

In 1932, during the heyday of pulp and in the midst of the Great Depression, a Mexican artist named José David Alfaro Siquieros was commissioned to paint an 18 by 80 foot mural on a wall above Olvera Street in downtown Los Angeles. Olvera Street at that time was a contrived copy of an idyllic Mexican village market, designed mainly to bring tourists to that part of town and help clean up L.A.’s image, which due to gangsterism and police corruption was as bad as those of places like Chicago and St. Louis. The mural’s theme was to be “Tropical America,” and when completed the piece would be partially visible from the street and would fully face City Hall.

But Siquieros was aware that all around Southern California police were breaking up union meetings, beating ethnic minorities and deporting Mexicans—even those who were American citizens—by the boxcar-load. So instead of the idealized tropical mural his benefactors expected him to unveil, he used spray paint and bold colors to create a shocking protest piece. The central figure of the mural was a Mexican or Indian man bound to a strange, double cross with an American eagle perched above, talons extended.

unveil, he used spray paint and bold colors to create a shocking protest piece. The central figure of the mural was a Mexican or Indian man bound to a strange, double cross with an American eagle perched above, talons extended.

The piece embarrassed city fathers. It was immediately condemned and whitewashed, but not forgotten. Almost from the day of its censoring, Mexican-American activists fought to have the mural restored and now they’re getting their wish. Because of the covering of white paint, the original piece survived where it would otherwise have weathered into nothingness. Now the white paint is being cleaned off, and what remains of the original mural is set to go on display in 2012, with a digital image projected on top to fill out the colors and missing segments.

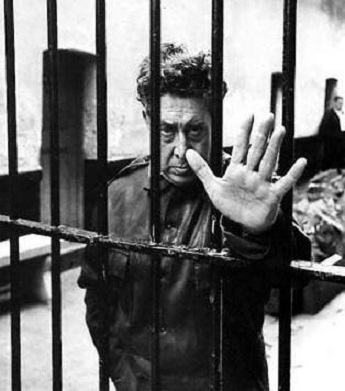

Siquieros died in 1974 after a long career and copious acclaim. One of his most enduring murals adorns one of the buildings of the UNESCO protected Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. When he wasn't paiting he found time to have many political adventures. For a time, he  was forced to go into hiding because of his close links to a group that tried to assassinate Leon Trotsky. His political activities cost him numerous commissions, yet the quality and influence of the pieces he completed was undeniable, and he continued to grow in stature.

was forced to go into hiding because of his close links to a group that tried to assassinate Leon Trotsky. His political activities cost him numerous commissions, yet the quality and influence of the pieces he completed was undeniable, and he continued to grow in stature.

Today his art resides in places as far flung as Teheran and Washington, D.C.’s Smithsonian Institute, which is kind of funny when you consider those two countries can agree on art but little else. But in any case, to the list of places where Siquieros has made a lasting mark, he'll be adding, almost eighty years late, L.A.’s Olvera Street.