| Vintage Pulp | Mar 28 2024 |

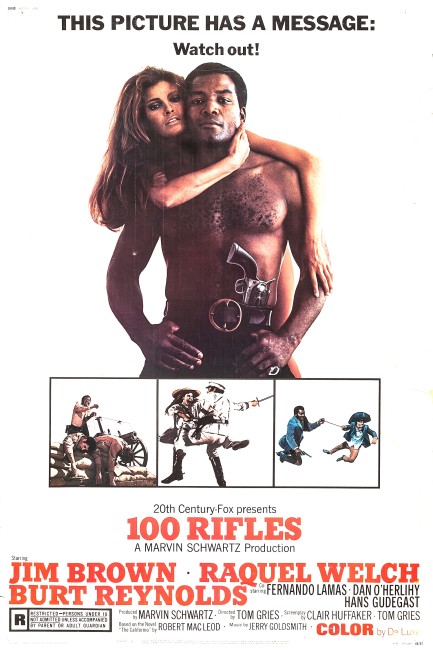

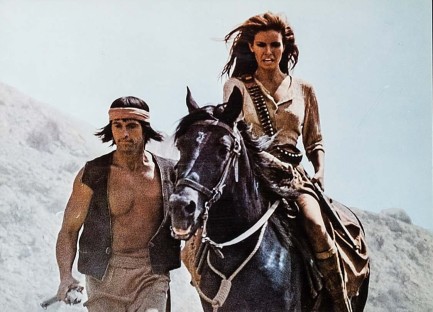

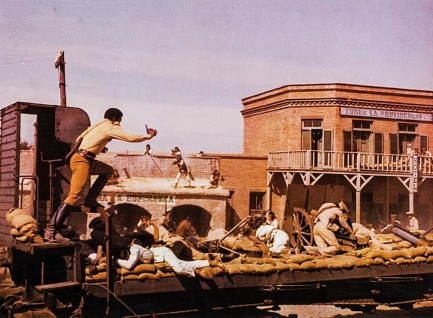

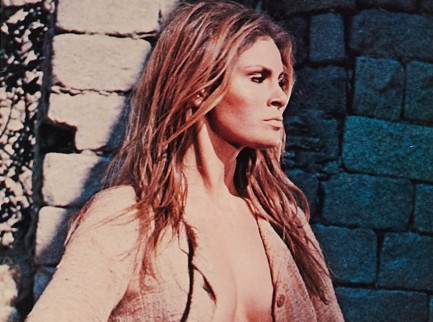

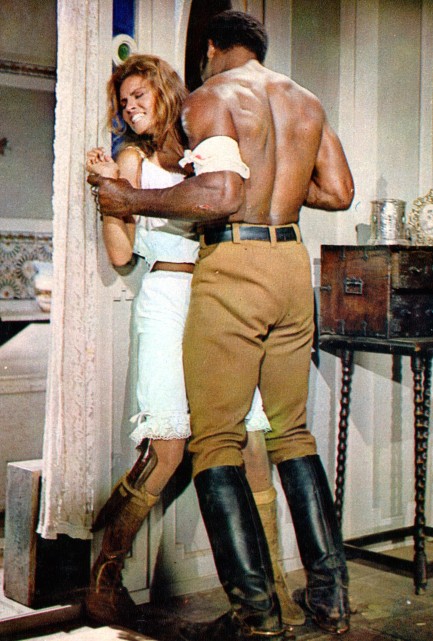

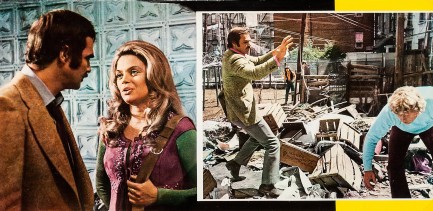

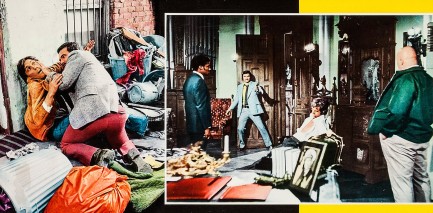

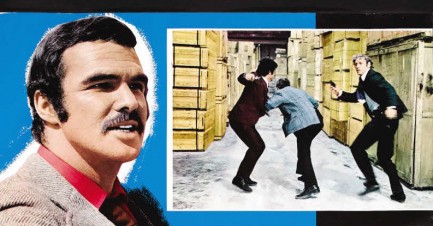

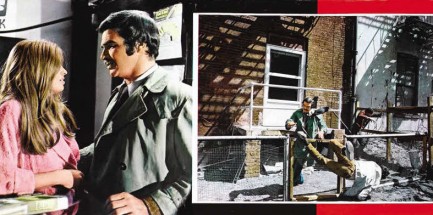

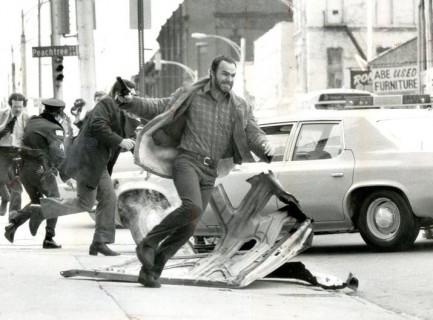

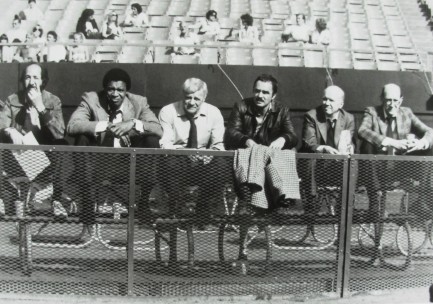

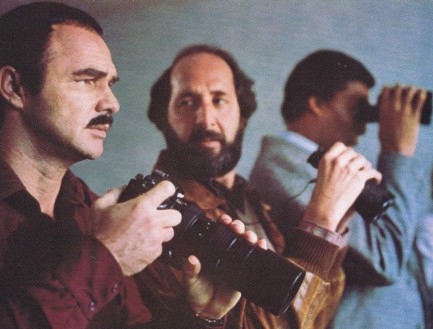

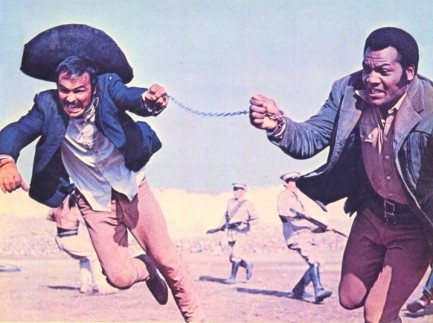

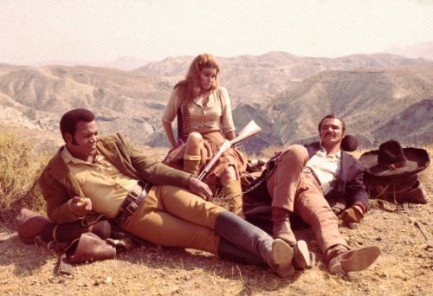

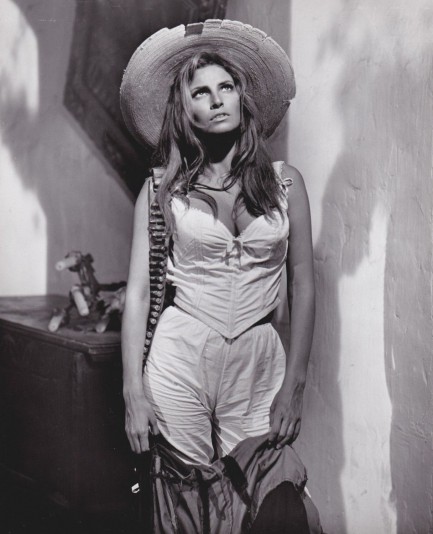

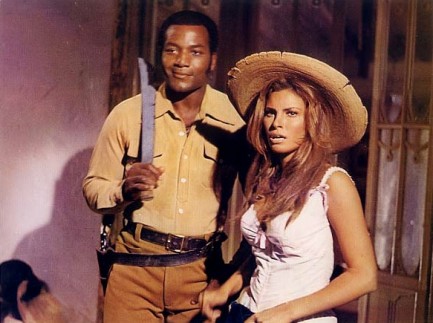

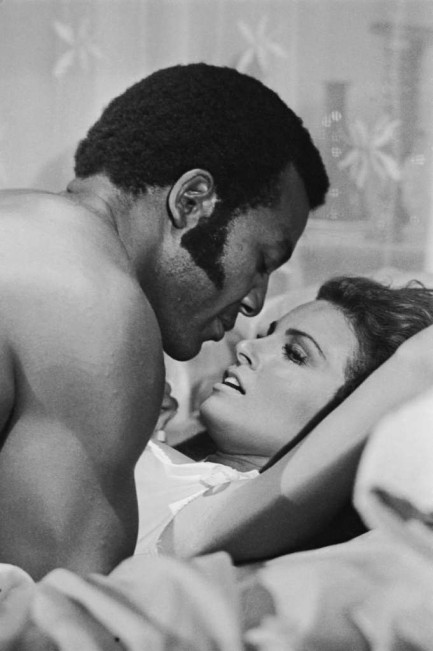

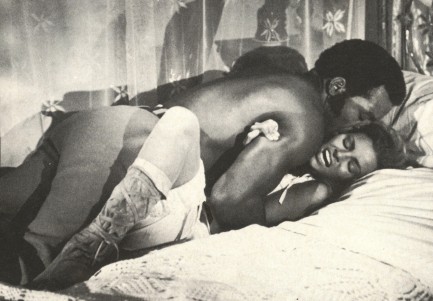

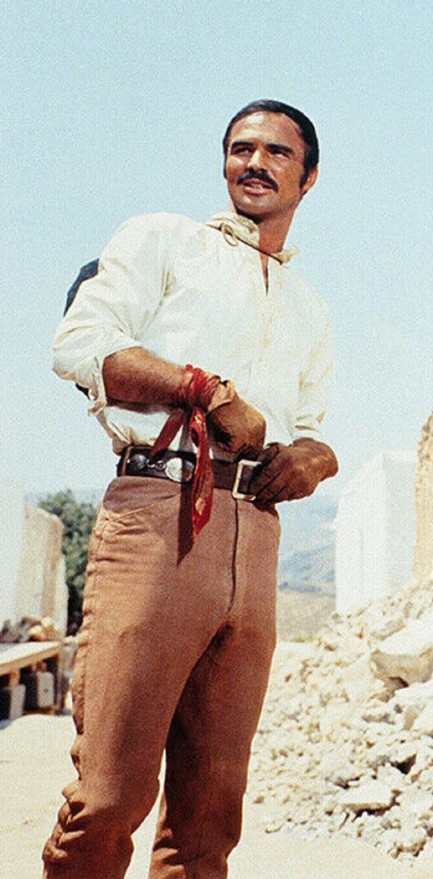

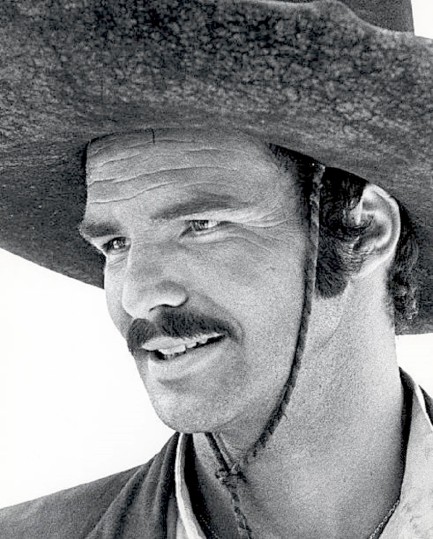

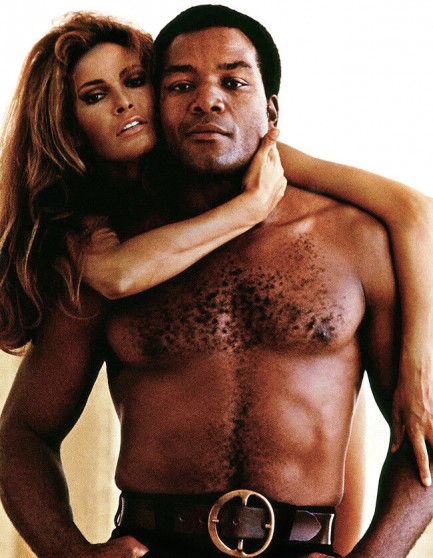

The western adventure 100 Rifles, which premiered in the U.S. today in 1969 and starred Burt Reynolds, Jim Brown, and Raquel Welch, is a shot that went wide of the mark. But even if it could have been better, it has very nice promo art. Above you see the U.S. poster and a few production images to go along with the ones we shared before. See those and read a bit about the film here.

| Intl. Notebook | Apr 24 2023 |

| Vintage Pulp | Jan 31 2022 |

| Modern Pulp | Jul 16 2016 |

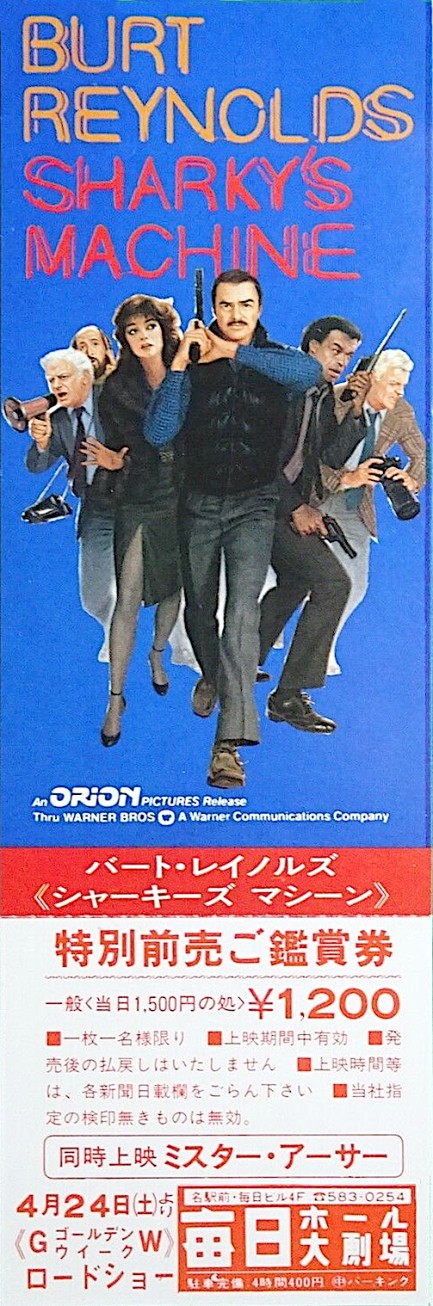

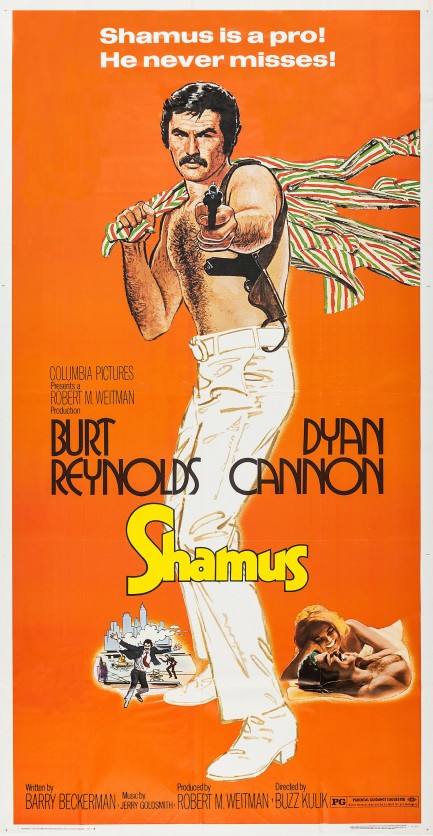

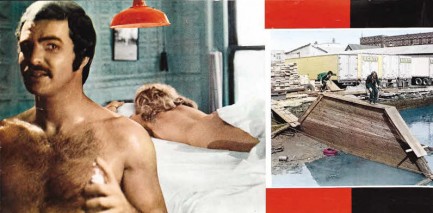

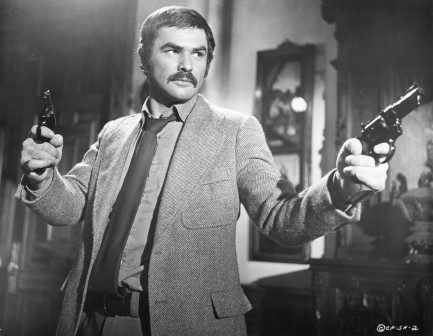

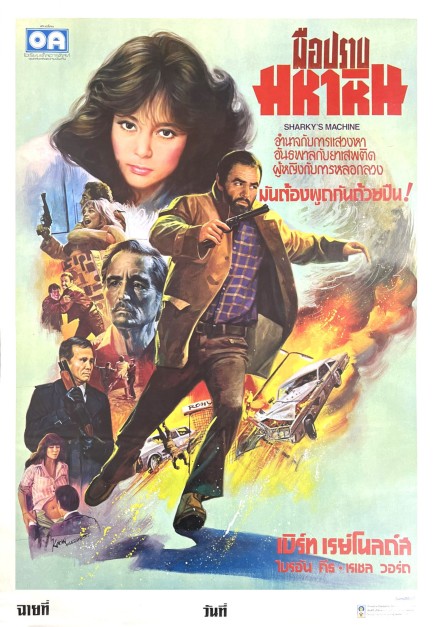

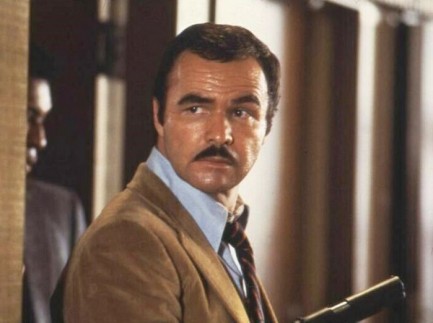

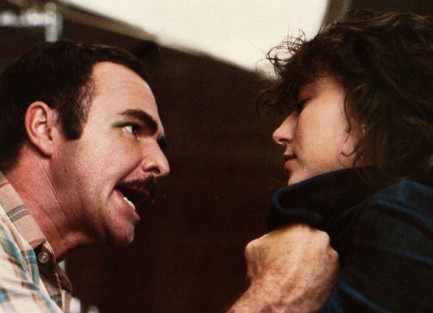

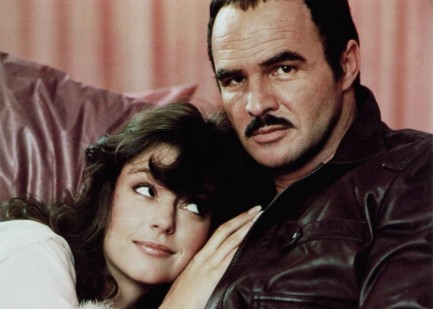

This poster was painted by the Thai illustrator Kwow for the 1981 thriller Sharky's Machine. Every blue moon or so Hollywood decides to update a ’40s film noir. Sometimes these are excellent movies—Body Heat as a rework of Double Indemnity comes to mind. Sharky's Machine is based on William Diehl's novel of the same name, which is a restyling of 1944's Laura. If you haven't seen Laura, a detective falls in love with a murdered woman, focusing these feelings upon her portrait, which is hanging over the mantle in her apartment. In Sharky's Machine the hero, Atlanta vice detective Burt Reynolds, falls in love with Rachel Ward via his surveillance of her during a prostitution investigation, and is left to deal with his lingering feelings when she's killed.

Ward observed years back that she had been too prudish in how she approached her roles, and we imagine this was one movie she had in mind. We agree with her. Reynolds' 24/7 surveillance of a high-priced hooker is not near frank enough. This is where vice, voyeurism, and sleaze as subtext should have come together overtly, as it does in Diehl's unflinchingly detailed novel, rather than as stylized montages, which is what Reynolds opts for.

Ward observed years back that she had been too prudish in how she approached her roles, and we imagine this was one movie she had in mind. We agree with her. Reynolds' 24/7 surveillance of a high-priced hooker is not near frank enough. This is where vice, voyeurism, and sleaze as subtext should have come together overtly, as it does in Diehl's unflinchingly detailed novel, rather than as stylized montages, which is what Reynolds opts for.

| Vintage Pulp | Aug 13 2015 |

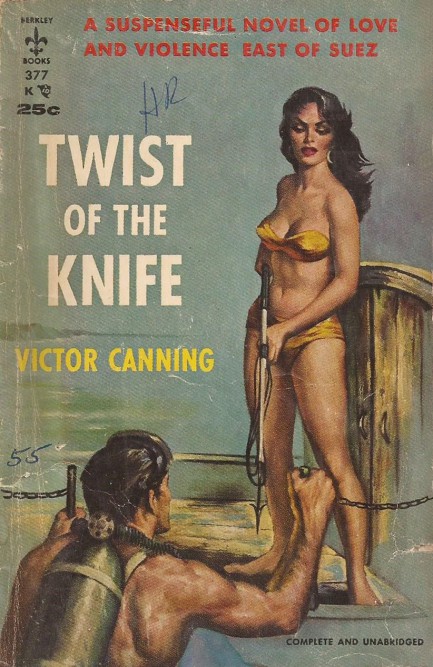

Interesting Charles Copeland cover art for Victor Canning’s 1955 adventure thriller Twist of the Knife, published outside the U.S. as His Bones Are Coral. It’s the story of a drug smuggler flying contraband from Sudan to Egypt who crash lands near the town of Suabar, gets involved in a caper to raise gold from the waters of the Red Sea, and of course beds the only white girl within sight. This was actually made into a really bad Burt Reynolds movie called Shark! in 1970.

| Vintage Pulp | Dec 26 2014 |

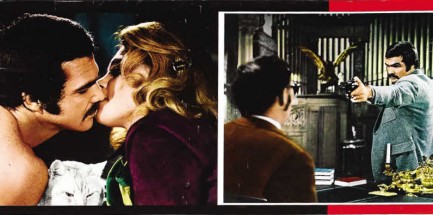

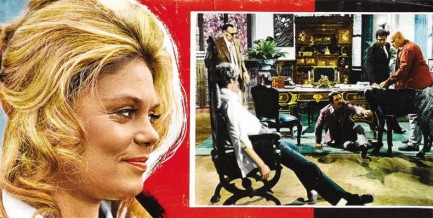

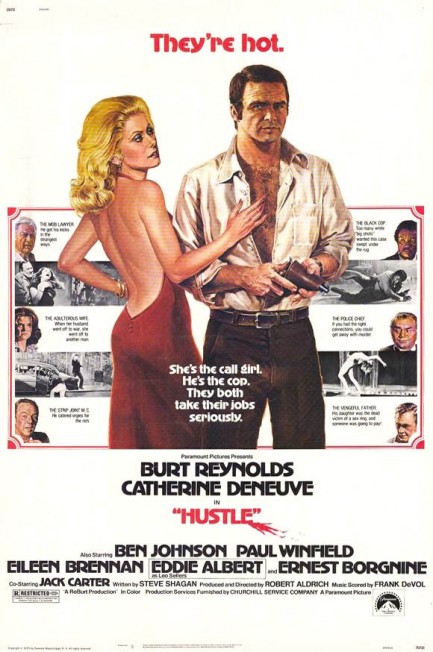

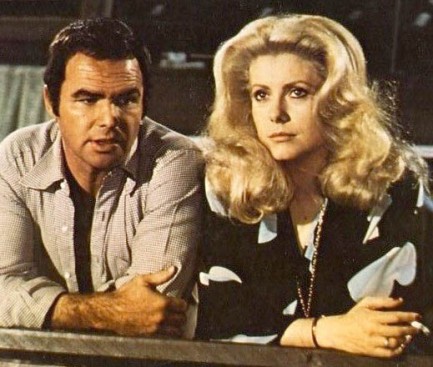

Paramount execs probably wet themselves when they finally made a deal to get American star Burt Reynolds and French icon Catherine Deneuve together onscreen. The promo poster tells us they’re hot—true, and it especially applies to Deneuve, who probably can't vent heat efficiently while shrouded beneath her enormous helmet of immobile, golden hair. You know those war flicks where a soldier in a ditch has a photo in his pocket of his beautiful girlfriend, and during lulls in combat he gazes at her and mutters about how he can’t wait to get back home to her? In Hustle Catherine Deneuve is a living version of that photo. Instead of being overseas she’s just across town, but she’s no less a signifier of impending doom than if she were a snapshot in someone’s pocket. We think writer Steve Shagan dropped the ball here, and not just by making her purpose in the film so obvious, but by making her role so thin. She has a key piece of evidence (she witnesses the villain making a phone call that leads to a murder) in a case that is never made, which we found bizarre. Hustle is mildly involving thanks to stylish direction and Reynolds’ innate watchability, but ultimately unsuccessful. It premiered in the U.S. yesterday in 1975.

| Vintage Pulp | Jun 3 2011 |

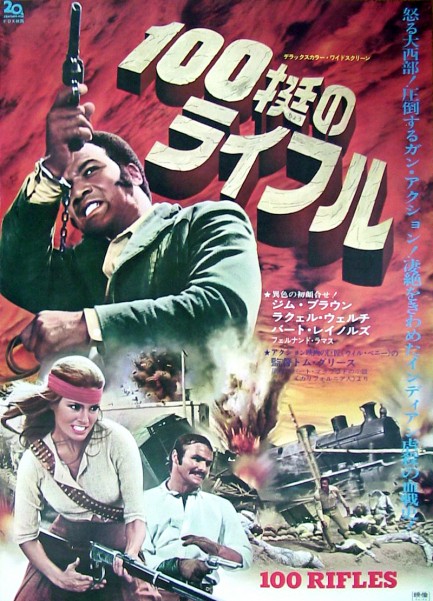

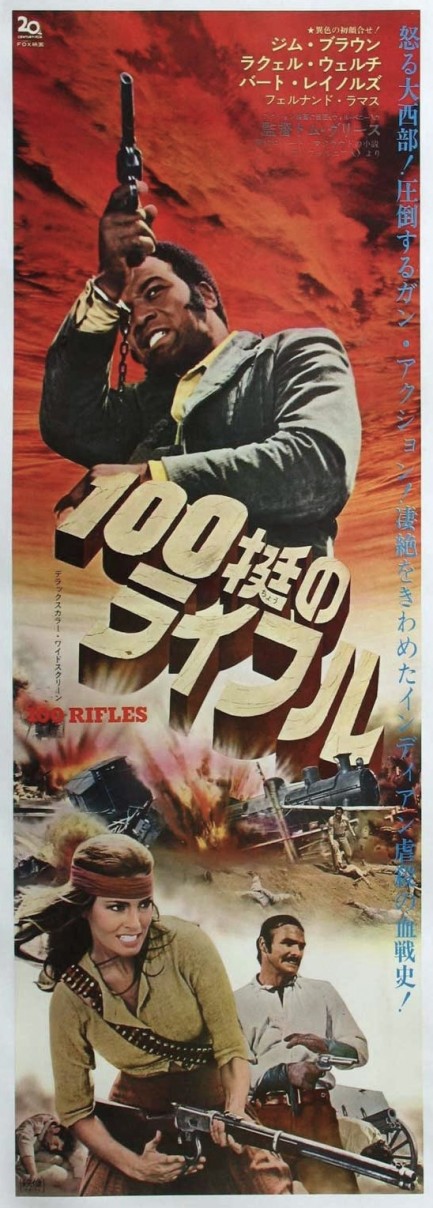

When we saw these Japanese posters for the 1969 western 100 Rifles, we made a special point to watch the film just so we had a good reason to share the art. So there you go. Now as for the actual film, there’s a moment about halfway through where mega sex symbol Raquel Welch says to black ex-NFL football star Jim Brown, “Do you want me?” That’s about as rhetorical a question as has ever been asked on a motion picture screen. Of course he wants her—who wouldn’t? But this being an American movie, the real question is, “What will the consequences be?” Because after all, even though interracial romance works just fine for millions of real life couples, in Hollywood that simply can’t be. Especially when you’re talking about heterosexual black males.

So we know someone’s going to end up dead. We could have prefaced that last statement with a spoiler alert, but we all know it wasn’t really a spoiler. As moviegoers, we’ve been trained to know happily-ever-after isn’t a component of these black/white love affairs. When 100 Rifles was made in 1969, it may have seemed America was on the way—if perhaps a bit turbulently—to a post-racial future. But forty-two years later  we bet you can’t think of three other instances where a top tier white starlet had a love scene with a black man. So even though 100 Rifles offers up a reasonably compelling tale of guerrilla warfare on the Mexican frontier, and Burt Reynolds co-stars in a role perfectly crafted for his special brand of smarmy brilliance, and you even get an unforgettable nude minute of cult siren Soledad Miranda, you mainly come away with yet another reminder of how edgy Hollywood was capable of being back then, and how risk averse it is today.

we bet you can’t think of three other instances where a top tier white starlet had a love scene with a black man. So even though 100 Rifles offers up a reasonably compelling tale of guerrilla warfare on the Mexican frontier, and Burt Reynolds co-stars in a role perfectly crafted for his special brand of smarmy brilliance, and you even get an unforgettable nude minute of cult siren Soledad Miranda, you mainly come away with yet another reminder of how edgy Hollywood was capable of being back then, and how risk averse it is today.

We don’t speak of risk merely in terms of race, but in general. Despite modern cinema being awash in CGI and 3D and THX sound and obscene budgets, as well as dozens of swaggering young stars, along with teams of clever writers and yachtfuls of execs who all claim to be mavericks, the movies are overwhelmingly soulless. 100 Rifles is not a great film, but even as a late-1800s period piece it asks relevant 1969-style questions about racial mixing, social struggle, and offers serious introspection about the worth of warfare. It's an interesting product of the time from which it sprang. That's worth a lot, in our book. By comparison, if we consider post-millennial movies a product of the time in which we now live, then the message seems to be: just don’t make us think.

| Vintage Pulp | Apr 9 2010 |

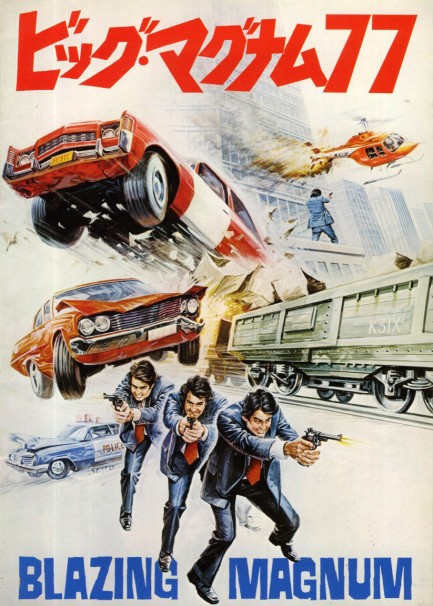

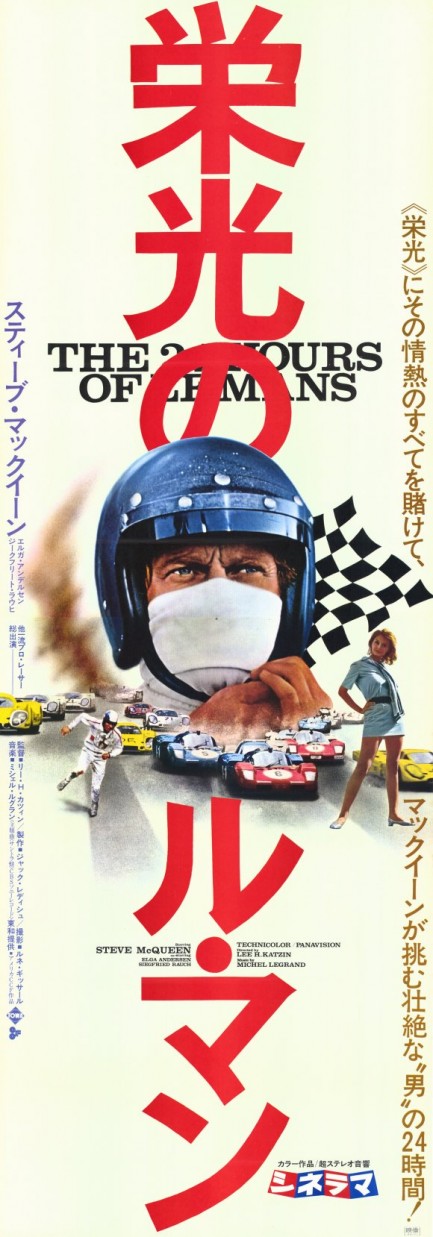

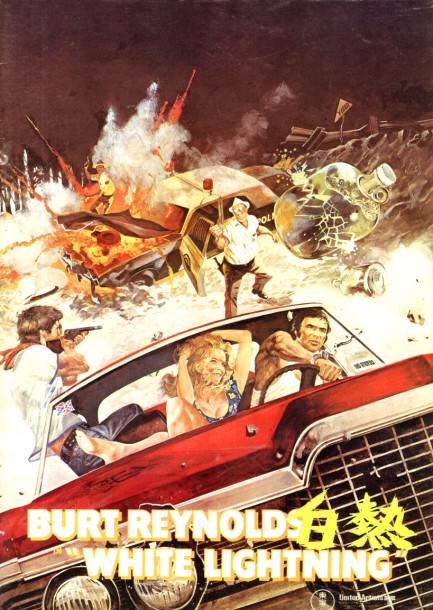

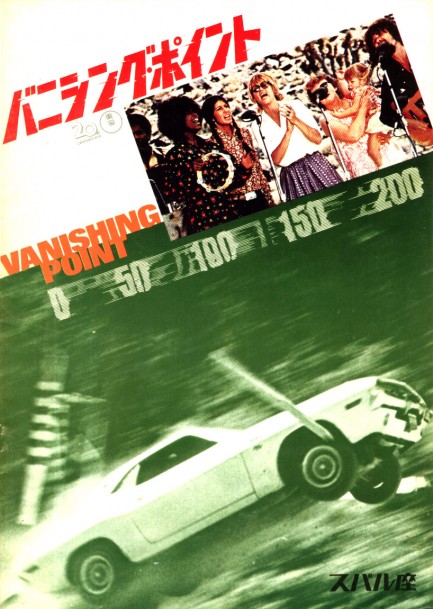

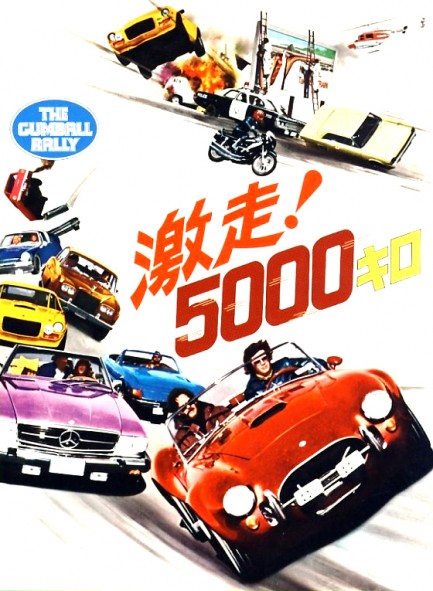

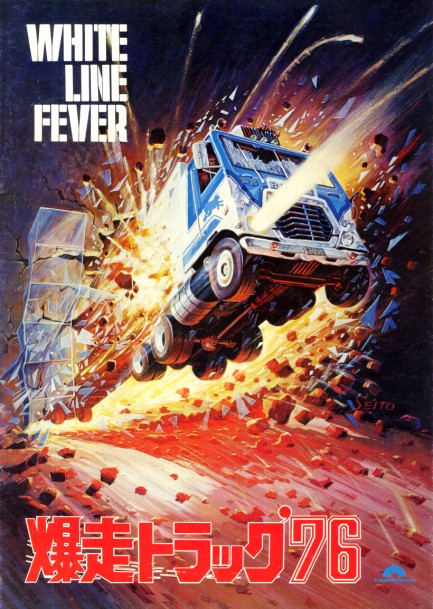

Yesterday, the Pulp girlfriends suggested that the only reason we posted all those album covers was because several of them featured nudity. We're just humble historians, chronicling mid-century art and discussing the social context within which it appeared—honest. But because our girlfriends called us voyeurs, we've decided to balance the scales a bit by posting something pretty much all women find exciting—crashing cars. Below is an assortment of Japanese posters for nine automotively-themed, vintage American movies. So there you go girls. If you don't find these exciting, well, we give up trying to figure you out.