| Vintage Pulp | Aug 11 2016 |

| The Naked City | Vintage Pulp | Jul 29 2014 |

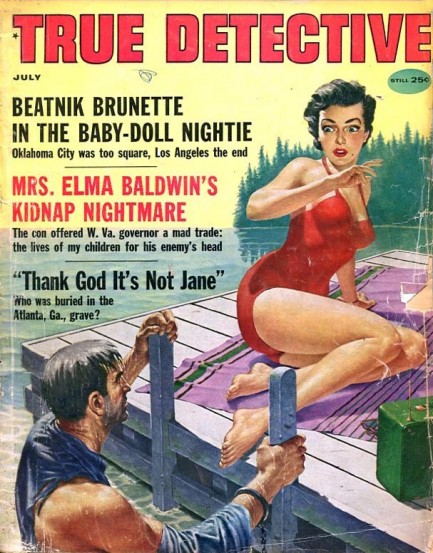

Above is a very nice True Detective from July 1959 with a Brendan Lynch cover depicting a woman startled by the arrival of a criminal. It’s actually a perfect cover, because inside the issue you get an interesting story related by Elma Baldwin, who was kidnapped by a paroled convict named Richard Arlen Payne. Payne snatched Baldwin and three her kids at gunpoint as part of an ill-conceived plan to trade them for the release of his former cellmate Burton Junior Post, aka Junior Starcher, who was serving time at West Virginia State Penitentiary in Moundsville. Payne didn’t want Starcher out because they were buddies. Quite the opposite—he had vowed to kill the man, and threatened to torture and murder the Baldwins if his demands weren’t met. He wrote in a note to Governor Cecil Underwood, “My purpose is to kill and take the head of my worst enemy, who is now out of reach. I must kill him or go mad.”

You’re probably asking why Payne never did anything to Starcher while they were cellmates. Payne’s  answer was simple: “I could have killed him at any time, and I thought about it very seriously. At times I had a blade to his throat. But he was as good as done for anyway, because I knew once I got in the free world there were ways that I could get at him.”

answer was simple: “I could have killed him at any time, and I thought about it very seriously. At times I had a blade to his throat. But he was as good as done for anyway, because I knew once I got in the free world there were ways that I could get at him.”

Well, maybe not so much. In any case, the kidnapping was big news in 1959, probably owing to its sheer incomprehensibility. Today it’s mostly forgotten but remains a good case study of the benefits of being able to let go one’s anger. The entire event lasted only twenty hours, ending with a brief shootout in which nobody was injured, followed by Payne’s admittance to a mental asylum. Asked if Starcher had done anything specific during their time at Moundsville to engender such hatred, Payne said, “Well, nothing I can put my finger on. It was just a sort of natural hatred.”

| The Naked City | May 26 2011 |

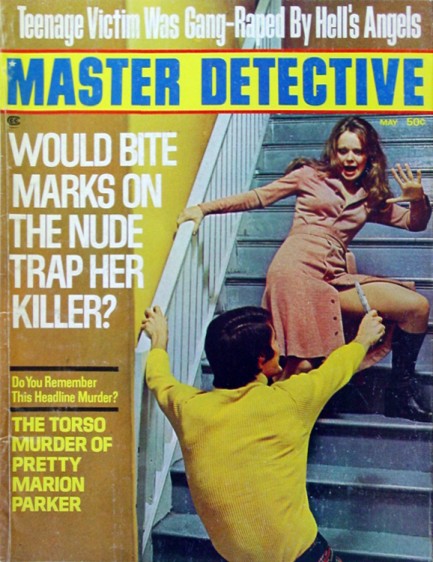

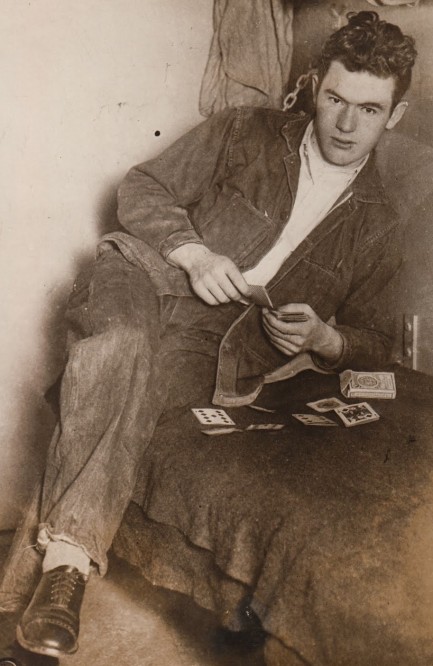

This May 1973 issue of the true crime magazine Master Detective delves back more than four decades to examine one of the most infamous murders committed in early twentieth century America. The victim was a 12-year old Los Angeles girl named Marion Parker, and on December 15, 1927, she was abducted from her school by a man who used to work for her father. The man—nineteen-year-old William Edward Hickman—came to the school and told the registrar that the girl’s father had been in an accident that morning and wished to see his daughter. It was not policy to release children to anyone other than their parents, but swayed by Hickman’s measured urgency and apparent sincerity, the registrar released Marion Parker into his custody.

Hickman was after money. Marion Parker’s father, a banker named Perry Parker, had it in abundance. For the next few days Hickman sweated Perry Parker, sending pleading notes written by Marion, as well as other notes demanding a ransom. Hickman signed the latter with various pseudonyms, but one in particular stuck with the press—“The Fox.” Eventually, Parker and Hickman agreed on a ransom of $1,500, to be paid  in $20 gold certificates. The first attempt at an exchange failed when Hickman noticed a cop near the meeting place. It’s unclear whether the policeman was part of a trap, but Hickman was taking no chances. He bailed, and set up a second meeting for a few nights later.

in $20 gold certificates. The first attempt at an exchange failed when Hickman noticed a cop near the meeting place. It’s unclear whether the policeman was part of a trap, but Hickman was taking no chances. He bailed, and set up a second meeting for a few nights later.

When Parker reached the rendezvous point he saw Hickman sitting in a parked car. Parker approached the driver side window and saw that the kidnapper was aiming a gun, and he also saw his daughter in the passenger seat, bundled up to her neck in a blanket. She couldn’t move—that was clear. She didn’t speak. Hickman took the ransom and drove quickly away, stopping just long enough to push Marion Parker out of the car at the end of the block. When Parker reached his daughter and lifted her into his arms he screamed in anguish. Marion was dead, and had been for twelve hours. Hickman had cut off her arms and legs, flayed the skin from her back, disemboweled her, and stuffed her with rags. She had been bundled up to conceal the fact that she had no limbs. Her eyes had been wired open so that she would, upon cursory inspection, appear to be alive.

Hickman had escaped, but he had left behind a clue that would lead to his capture. Among the rags he had stuffed into Marion Parker’s empty abdomen was a shirt with a laundry mark that police were able to trace to an address in Los Angeles. Twenty cops descended on a residence that turned out to be occupied by a man named Donald Evans, who was cooperative but said he knew nothing about Hickman. In truth Evans was Hickman, but by the time police figured that out he had fled to the Pacific Northwest. But he hadn’t run far enough. Wanted posters reached every corner of the west coast within days, and just one week after Hickman’s disappearance two police officers in the town of Echo, Oregon recognized him and arrested him.

cooperative but said he knew nothing about Hickman. In truth Evans was Hickman, but by the time police figured that out he had fled to the Pacific Northwest. But he hadn’t run far enough. Wanted posters reached every corner of the west coast within days, and just one week after Hickman’s disappearance two police officers in the town of Echo, Oregon recognized him and arrested him.

At trial, Hickman claimed to be guided by voices—one of the first times, if not the first, that this type of insanity defense was attempted in an American courtroom. But the jury wasn’t buying any of it and they convicted Hickman of murder and kidnapping. The judge sentenced him to be executed at San Quentin State Prison, and he climbed the stairs to the gallows on October 19, 1928. Hickman had once been smooth enough to talk a school official into sending Marion Parker to her doom, and had calmly lied about his identity to twenty cops who had burst into his house. In prison he had corresponded with and impressed author Ayn Rand so much that she decided to base a character on him because he embodied her mythical “Nietzschean Superman” ideal. But at the end, all of Hickman’s considerable aplomb deserted him. Just before the hangman sprang the trapdoor that would cast him into oblivion, he collapsed babbling in fear. His last words were, “Oh my God! Oh my God!”