| The Naked City | Nov 30 2022 |

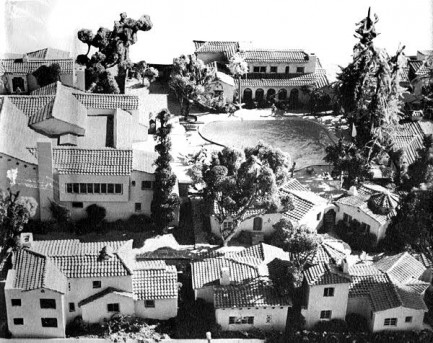

| Hollywoodland | Sep 1 2020 |

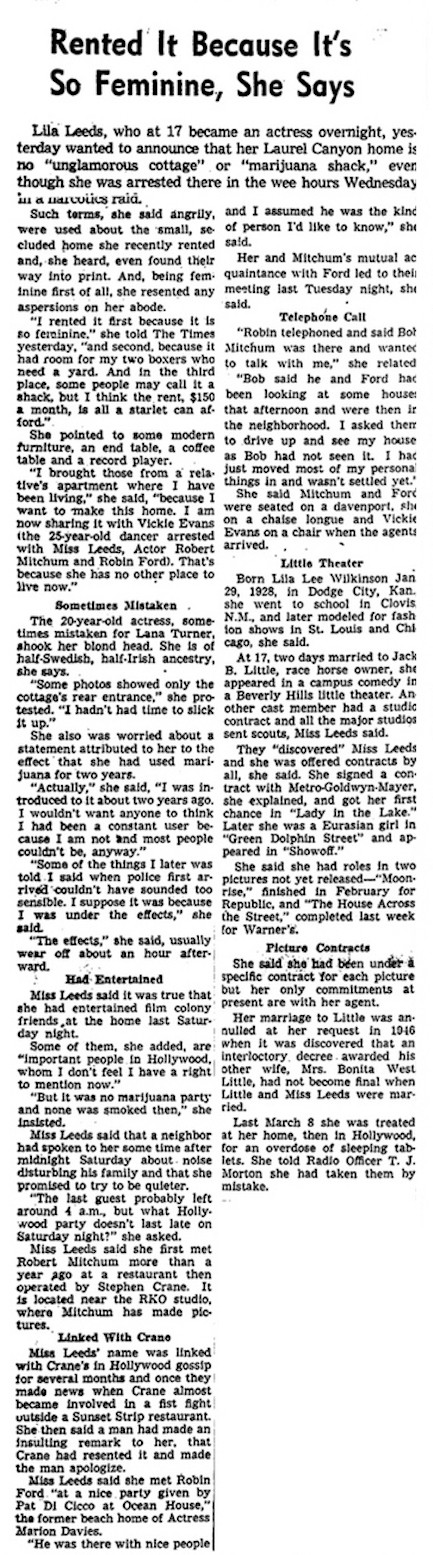

the place because it was feminine, and because it had space for her two dogs. She also admitted that she used marijuana, which considering she hadn't gone to trial yet maybe wasn't a great idea.

the place because it was feminine, and because it had space for her two dogs. She also admitted that she used marijuana, which considering she hadn't gone to trial yet maybe wasn't a great idea.

| Mondo Bizarro | Feb 24 2012 |

This photo appeared in the Los Angeles Times and other newspapers this month in 1942 after West Coast anti-aircraft batteries opened up on a mysterious aerial object supposedly seen hovering in the skies above L.A. The object was sighted in the early morning of February 25 and fired upon for about two hours. The next day Army spokesmen said the barrage had been the result of a false alarm caused by war hysteria, which leaves you to wonder what sort of non-existent object could be pinned by multiple searchlights as it moved across the sky.

Another official explanation was that the object was a weather balloon, which of course raises a completely different question, namely, how did more than 2,000 exploding artillery shells fail to bring down something so flimsy? These shells caused three deaths on the ground, and they weren’t even aimed there. UFO aficionados, of course, say it was an alien craft. That’s debatable, not for any scientific reason, but based on simple logic. Consider: we puny humans have already made major advances in stealth tech, yet we think we’d be able to detect an alien craft that came from the gulfs of space to observe us? That’s called pure hubris, and we don’t subscribe.

So that leaves one other explanation. It was a deliberate Army drill involving a weather balloon, an exercise designed to test anti-aircraft capabilities, shock Los Angeles residents and thus gauge the potential for mass panic, and ram home the idea to the masses that the Japanese were lurking out there somewhere. In order to believe this scenario one has to assume the anti-aircraft gunners had the shittiest aim in the history of hurled projectiles, however the three obvious benefits we’ve listed for conducting such a drill make this by far the most logical scenario. Of course in the end, we weren’t there, so we’re only speculating about this obscure historical event. We can be sure of only thing—there will never be a definitive answer.

of hurled projectiles, however the three obvious benefits we’ve listed for conducting such a drill make this by far the most logical scenario. Of course in the end, we weren’t there, so we’re only speculating about this obscure historical event. We can be sure of only thing—there will never be a definitive answer.

| Intl. Notebook | Feb 6 2012 |

What you see here, which we found on the great architecture forum Skyscraperpage.com, is a clipping from the Los Angeles Times showing the glare of an atomic bomb explosion. The shot was taken from atop the L.A. Times Building, and the light is from the 34 kiloton nuclear test codenamed Fox, which took place in the desert near Las Vegas, more than 300 miles away. Of course, the clipping has yellowed with time, but below you can see what the shot looked like originally. There were hundreds of photos of this type made during the heyday of U.S. atomic bomb testing, and with a glance around the web you can find many of them. This one happened today in 1951.

| Mondo Bizarro | Aug 23 2010 |

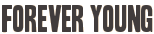

In Los Angeles on Friday, two women working in the famous Glen-Donald building in the city’s MacArthur Park neighborhood found the remains of two infants in a locked steamer trunk. One infant was in embryonic form, while the other had reached full term; one was wrapped in a 1933 edition of the Los Angeles Times, while the other was wrapped in a 1935 edition. The trunk was labeled Jean M. Barrie, and contained postcards addressed to her, as well as other items, including ticket stubs to the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics. But who, exactly, Jean M. Barrie was, is unclear.

The papers in the trunk indicate she may have been a nurse who lived in Los Angeles around that time, but the Glen-Donald building would have been an unlikely residence for such a person because it was a ritzy address in the 1930s, a place where galas were staged in a grand basement ballroom. However, there was at least one other Jean M. Barrie alive in the 1930s—the woman you see in the above ad from a 1918 issue of The Lyceum Magazine. This Jean M. Barrie was a relative of Peter Pan author James M. Barrie and a semi-famous storyteller in her own right.

Authorities are pursuing the lead because the trunk contained a copy of Peter Pan and a membership certificate for the Peter Pan Woodland Club, located in Big Bear, California. It also seems much more likely for this second Jean M. Barrie to have lived at the Glen-Donald building, however it’s unclear whether she ever lived in Los Angeles at all. Only a detailed investigation will tell which woman—the anonymous nurse or the well-known storyteller—owned the steamer trunk. In the meantime, LAPD pathologists are examining the infants in an effort to determine why they never got to live their lives.

| Intl. Notebook | Mar 30 2009 |

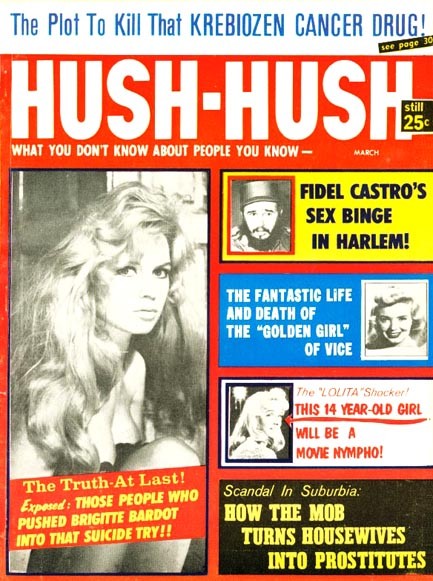

We’ve posted another nice Hush-Hush cover, this one from March 1961, with Brigitte Bardot, Fidel Castro and Sue Lyon on the cover. These tabloids always have such intriguing headlines, so this time we decided to do a bit of research on the stories. What we found was way too interesting not to share, so if you fancy a trip in the Wayback Machine to the year 1961, read on.

The drug Krebiozen, which is mentioned on the banner across the top of the magazine, was an experimental cancer treatment extracted from horse’s blood. Bad as that sounds, it gets downright gruesome when you consider that one horse yielded one gram of the drug, and the extraction process was fatal. That means treating America’s cancer patients would have required the death of every horse on the planet, along with some donkeys and mules, and possibly even a few humans with horsey features. But potential equine extinction isn’t what killed Krebiozen—what happened is its inventor, an Italian doctor living in Argentina named Stevan Durovic, refused to divulge to the American Medical Association or Food & Drug Administration precisely how Krebiozen was made for fear communists would get ahold of it. Or put another way, Dr. Durovic used his political beliefs as an excuse to duck legitimate questions from legislative bodies empowered to ask them.

As the saying goes, if it ducks like a quack it probably is a quack, and there seems little doubt that’s exactly what Durovic was. In the end, a very pissed-off FDA tested a reverse-engineered version of Krebiozen, which showed no discernible benefits for cancer patients. The question of whether they correctly manufactured the drug remains, but we don’t know the answer. What intrigued us most about this story was the fact that no contemporaneous articles we read expressed an iota of concern for potentially millions of slaughtered horses, nor Durovic’s stunning violation  of his Hippocratic oath by publicly wishing harm on innocent cancer patients in the Eastern Bloc. Though we are retro fetishists here, we don’t believe the past, as a rule, was a better time—only that it was more glamorous and, during the 60s and 70s, more artistically daring and sexually freewheeling. None of those qualities compensates for its shortcomings, which the Krebiozen story makes clear.

of his Hippocratic oath by publicly wishing harm on innocent cancer patients in the Eastern Bloc. Though we are retro fetishists here, we don’t believe the past, as a rule, was a better time—only that it was more glamorous and, during the 60s and 70s, more artistically daring and sexually freewheeling. None of those qualities compensates for its shortcomings, which the Krebiozen story makes clear.

Moving down the page, the story about Bardot struck us for one reason—we never heard she was suicidal. We’re actually embarrassed not to have known, but since our go-to reference site—ahem, IMDB—made no mention of attempted suicide, we were clueless. Of course, once we looked elsewhere, several comprehensive bios mentioned it. Bardot’s words on the subject are unflinching: “I really wanted to die at certain periods in my life,” she wrote in her autobiography. “Death was like love, a romantic escape.” It was so romantic an escape, in fact, that she tried to off herself more than once. We think the suicide try referenced by Hush-Hush occurred in 1958, when the Los Angeles Times reported Bardot had swallowed a bunch of sleeping pills after a nervous breakdown in Italy. Probably the maddening Rome traffic pushed her over the edge, which is totally understandable.

Next we hop across the page to where Hush-Hush presses the button marked X for xenophobia: Fidel Castro did indeed visit Harlem. In 1960 he was invited to New York City to speak at the United Nations. His delegation was supposed to stay at the swanky Shelburne Hotel on Lexington Avenue, but when they arrived the management asked his delegation for a $10,000 cash deposit. We don’t know much about lodging diplomats, but that seems a bit unusual, in our view. You’d think details such as payment would have been taken care of in advance, via either the UN or the host government. Anyway, Castro got upset and made a pretty big stink about it, even famously threatening to sleep in Central Park. In the end the Hotel Theresa in Harlem came to the rescue by offering the Cuban delegation rooms, and when Castro arrived there African American crowds turned out in the streets to either cheer him, or

curiously observe him, depending on which accounts you believe. We doubt Hush-Hush’s contention that the visit was some sort of sex holiday, but even if it were, La Barba was divorced at the time, so it wasn’t as if he committed infidelity. In-Fidel-ity. See how we did that?

curiously observe him, depending on which accounts you believe. We doubt Hush-Hush’s contention that the visit was some sort of sex holiday, but even if it were, La Barba was divorced at the time, so it wasn’t as if he committed infidelity. In-Fidel-ity. See how we did that?

The last item we wanted to mention is the one concerning The Golden Girl of Vice. This is a reference to a woman named Patricia Ward, who was an aspiring actress pressed into prostitution by her boyfriend, oleomargarine heir Minot F. Jelke. That’s right—oleomargarine. Good Luck oleomargarine, to be precise, whose slogan was “the finest spread for bread.” Telling you, we couldn’t make this shit up if we wanted to. Apparently Jelke needed an income because his family had cut him off. The fine Ms. Ward proved able, if not necessarily willing, to go ho strolling with the intent of spreading for bread. The whole tawdry set-up fell apart and Ward’s next stroll was into court, where she was the star prosecution witness against Jelke in his pimping trial. The proceedings ended in a guilty verdict and Jelke languished upstate for twenty-one months. The Golden Girl of Vice apparently died sometime before 1961, but we know not when, where or how.

So there you have it—everything you always wanted to know about ’60s tabloid headlines but were afraid to ask. We could have researched more deeply into these stories, but frankly, actual writing was not part of our plan with this website, and we’re way over our weekly limit already. We’ll just add that a cable movie was released in the U.S. in 1995 that revisited the Golden Girl of Vice scandal. It was entitled Café Society and starred Frank Whalley as Minot F. Jelke and Lara Flynn Boyle as Patricia Ward. Reviews were generally favorable and the filmmakers presented a very stylish portrait of mid-century New York City. Might be worth a glance. Now, get back to work people.

For an update on this story click here.