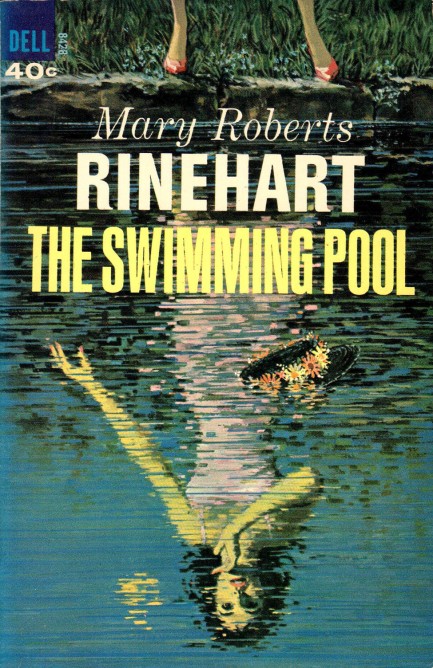

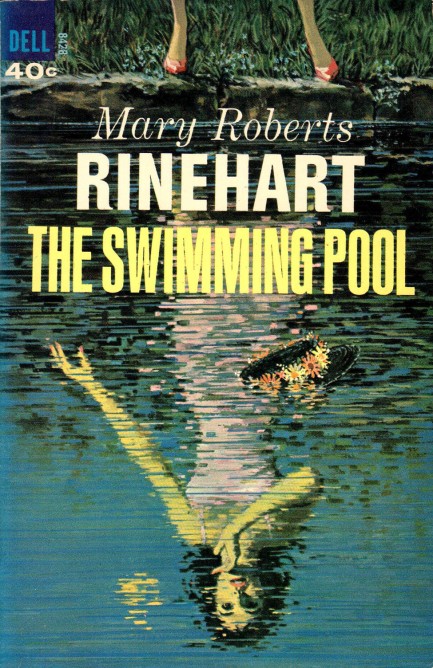

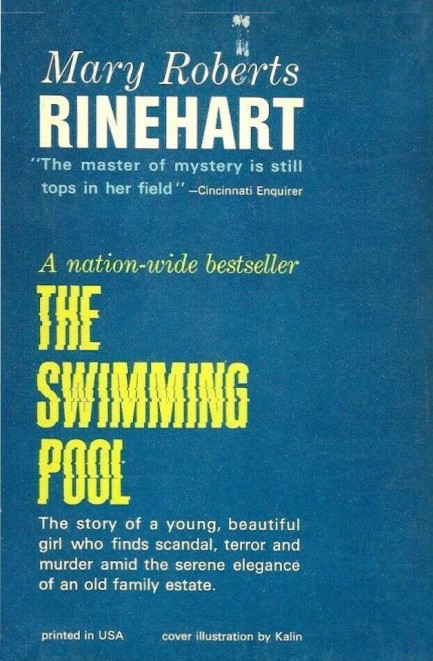

The thrills get lost in the deep end of Rinehart's final novel.

Mary Roberts Rinehart is another of those legendary mystery writers from the pulp era, having launched her career all the way back in 1908. The phrase, “The butler did it,” derives from her work. Of her many novels, we chose to read her 1952 effort The Swimming Pool and our reason was simple—we loved the cover. It was painted by Victor Kalin in a different style than we'd ever seen from him. So with excellent art fronting the work of a major author, we sat down, rubbed our hands together, and thought: “Okay, here we go.” And long story short, The Swimming Pool was definitely too slow to enjoy. And we have a suspicion Rinehart knew it, as her use of foreshadowing to sustain interest is incessant:

Perhaps that excuses her for what happened years later.

I daresay any train east from that Nevada city carries its own load of drama, but I had no idea it was carrying ours.

She was terrified, although it was only after long months of what I can only call travail that we learned the reason for it.

But those inquiries of hers eventually led to her tragic undoing.

And so forth. It occurs particularly at the end of chapters, but it pops up numerous times in other places. It was combined, as well, with the technique of having characters withhold information. We don't mean clandestinely. We mean openly, as in: “I'm not going to tell you that right now. Later perhaps, but not now.” We could have weathered this if it had been only a single character who knew more than he/she said, but there are two important ones here who simply won't speak up. It's a style. We get it. But in real life we'd be like: “Oh you better believe you're going to tell me what you know or this day is going to turn all kinds of bad for you.”

The story deals with two sisters living in a luxurious but neglected estate. The younger sister is a novelist of middling success, while the older one is basically a socialite. For months this older sister has been living in terror, but refuses to tell anyone what the danger is or accept help for her problem. Soon mysterious events occur, such as strange people creeping around the estate, someone taking potshots with a pistol, and a woman drowning in the titular swimming pool. Protection seems to miraculously arrive in the form of a studly renter for the estate's guest cottage, but he has his own agenda, which he reveals at the pace of Chinese water torture.

In fact, Rinehart's entire narrative feels padded, or deliberately drawn out in service of a word count. But here's the thing—she can certainly write. Who are we to even say that? Of course she can write. She published hundreds of stories, scores of novels, and saw her work adapted to cinema or television something like fifty times. But what can we do? We like what we like. The pacing of The Swimming Pool eventually wore us down. We learned only after reading it that it was her last novel, published when she was seventy-six. So we're thinking her spark might be brighter earlier. That means we'll try her again sometime. A serious reader of crime novels could do no less.

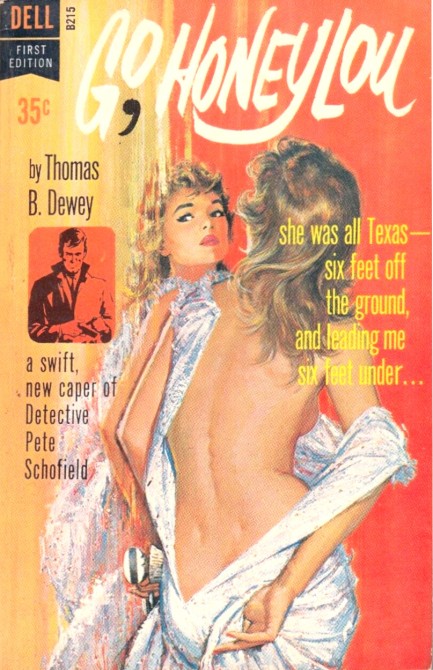

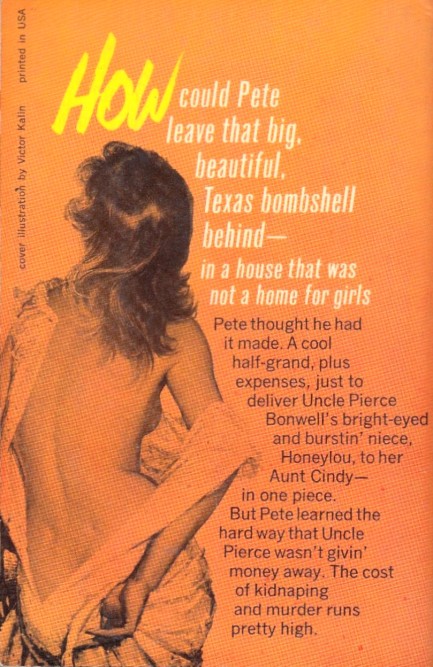

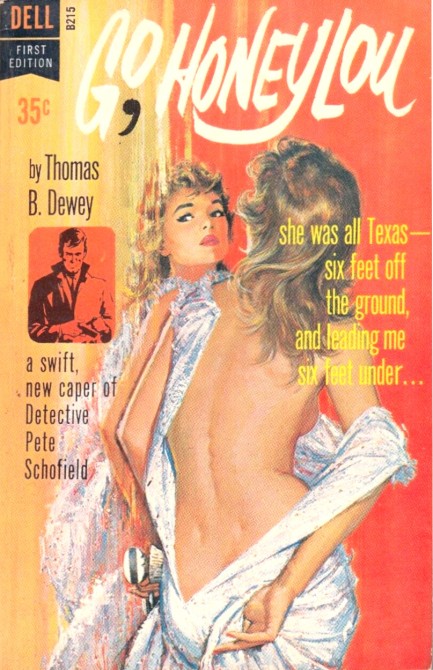

As detective capers go, this one is a real Honey.

Victor Kalin painted this beautiful cover for Thomas B. Dewey's Go, Honeylou, published by Dell in 1962. The blurb describes the book as a “swift new caper,” and that's true. Private eye Pete Schofield is hired to drive a beautiful 6-foot bumpkin named Honeylou from L.A. to San Francisco. It's a strange request, considering a detective's high rate of pay, which is probably why Schofield doesn't seem surprised when he's immediately tailed, soon harassed, eventually beaten, and finally robbed of his human cargo. He next finds that all along he was delivering Honeylou to a whorehouse, that her guardian aunt has been murdered, and a massive cache of her money is in the wind. It all worked fine for us, however Go, Honeylou was written well into a Pete Schofield series, and we'd have preferred to start with book one. But whaddaya gonna do? We've since noticed a couple of earlier entries out there at good prices. Since this one was good, we might buy those and report back.

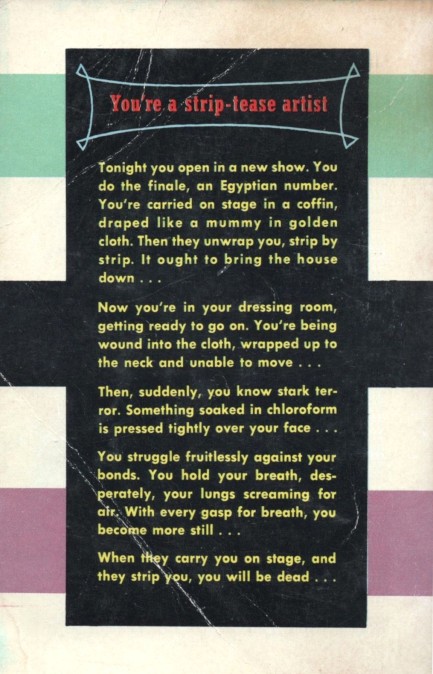

She was bound to have trouble.

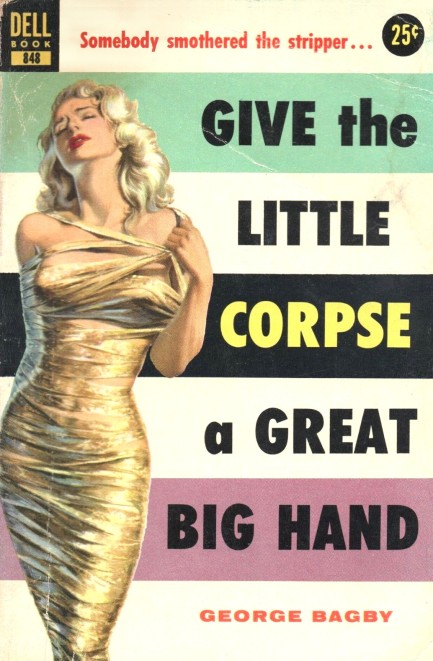

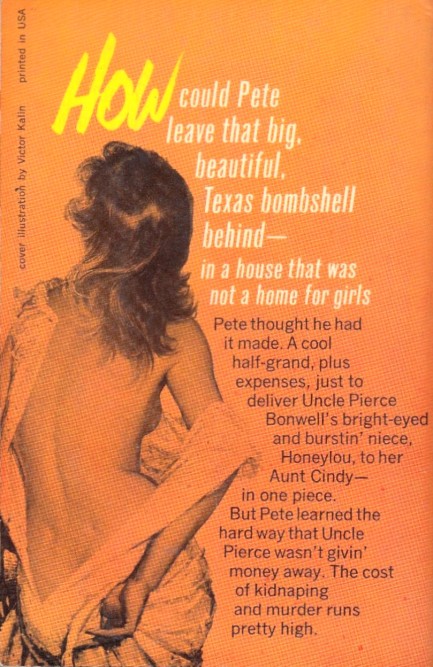

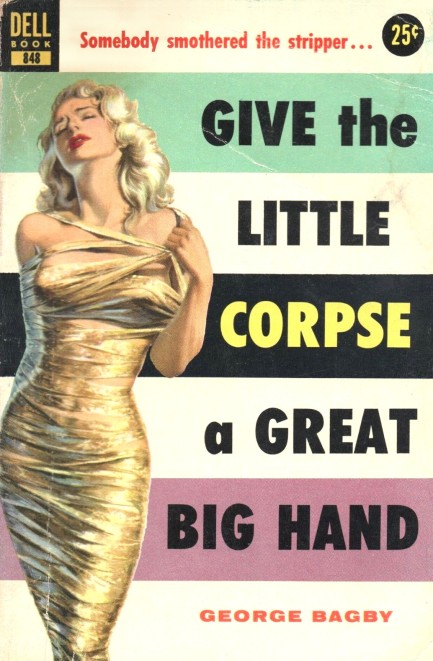

1953's Give the Little Corpse a Great Big Hand by George Bagby, aka Aaron Marc Stein, is a murder tale in classic whodunnit style about a burlesque performer named Goldie Gibbs who's debuting a routine at the famed but fictive Limehouse Club in which she's wrapped like a mummy and carried onstage in a golden coffin from which she rises and strips. Unfortunately, Goldie never rises because she's been murdered. On the case is New York City homicide inspector No-First-Name Schmidt.

Schmidt had been a franchise character for Babgy since 1936 and would eventually star in fifty-plus novels, the last in 1983. Here he cycles through various suspects with incisive questioning, and soon finds links between the murder, the local organized crime kingpin, and a spate of jewel robberies that happened the same night, while also learning that a colleague's daughter who sings at the Limehouse Club has some connection to the crime—unwittingly, beyond a doubt, because she's a “sweet kid.”

This and the other Schmidt books are narrated not by the inspector, but by a journalist named George Bagby—yes, same as the author—who publishes the tales in a magazine. From first person point-of-view Bagby gives readers the procedural details of the case, while also admiring his friend's great intelligence. Give the Little Corpse a Great Big Hand is mostly interrogations and speculations. While we've grown to prefer authors who build books a bit more around action, Bagby/Stein's all-brains approach works fine, and for whodunnit fans we'd call this a necessary read.

Moving on to the cover, it was painted by Victor Kalin and it's a nice effort, capturing the doomed Gibbs' shimmery gold mummy wrapping as described in the text, but taking a non-literal approach otherwise. We guess painting a dead woman in a coffin wasn't considered enticing, so Kalin came up with this moment that doesn't occur in the story but mirrors her distress. He made the right decision, and the result is eye-catching, as usual with his work. Check here, here, and here for examples.

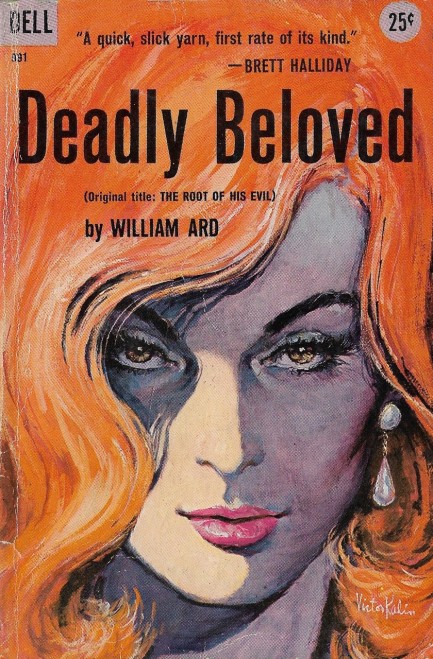

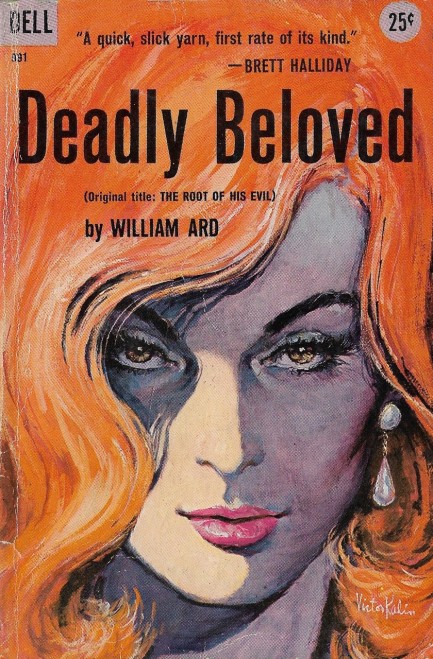

Packed with flavor and fortified with the recommended daily allotment of vitamin f.

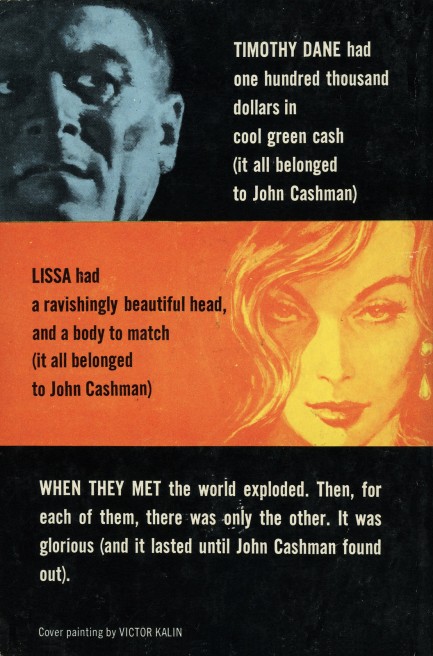

Victor Kalin went the tight focus route with this cover of an orange femme fatale he painted for William Ard's 1958 thriller Deadly Beloved, also published as The Root of His Evil. We love the art, and we loved the book too. An insurance investigator named Tim Dane is hired to transport a $100,000 gambling debt from an unlucky loser to a Miami hood named John Cashman. Cashman plans to use the money to help finance a war in Latin America, but that's just background. The more immediate part of the narrative involves an exotic dancer named Lissa, real name Elizabeth Ann Miller, who he has ringfenced with the help of 24/7 bodyguards and a lifetime management contract. Dane ignores warnings to keep away and is soon giving Lissa deep nocturnal lovin'—a pleasure that could cost his life if Cashman finds out about it. Ard, who also wrote as Ben Kerr, Mike Moran, et al, is a talented stylist with an approach all his own. His way of cutting transitional exposition is pretty neat. Every writer is required to do it, but Ard can cross town within the space of a sentence and still not sound like he's rushing. We're already trawling the auction sites for more from him. Highly entertaining.  Edit: We got an e-mail asking exactly what we meant by "cutting transitional exposition." We don't want to search through the book for an example, so we'll make up one. It would go something like this. "He decided he'd have to drive to Coral Gables to ask Cashman in person, and two days later when the door opened to his knock, he was surprised that it wasn't a servant but Cashman himself who answered."

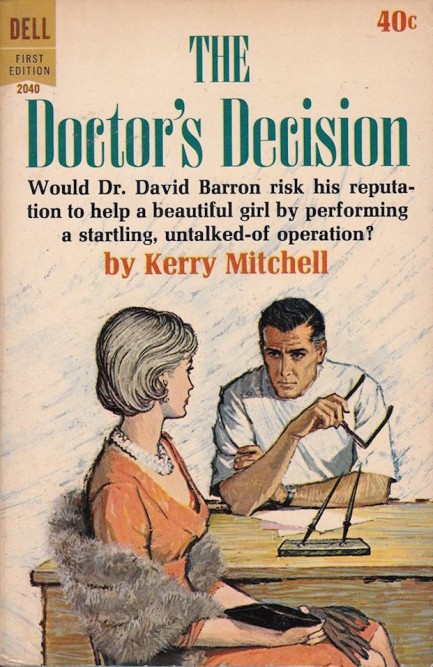

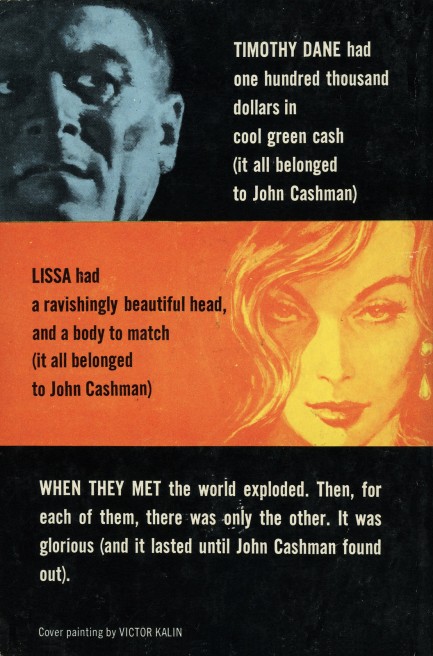

Well, your health coverage looks comprehensive, so I've decided to give you top notch care.

Yet another medical cover today, this one for 1967's The Doctor's Decision by Kerry Mitchell. The art is credited to someone named only Kalin. We think it's safe to conclude that's Victor Kalin, the veteran Dell Publications illustrator behind such classic fronts as Somerset Maugham's Rain and John D. MacDonald's Soft Touch. The author, Kerry Mitchell, was a pseudonym used by several writers, including Lee Pattinson, Ray Slattery, and Richard Wilkes-Hunter, and this tale deals with a plastic surgeon named David Barron who pioneers a radical new surgery, while simultaneously seeing his reputation threatened by scandal. We've run across Mitchell before. Remember Bush Nurse? That's our fave.

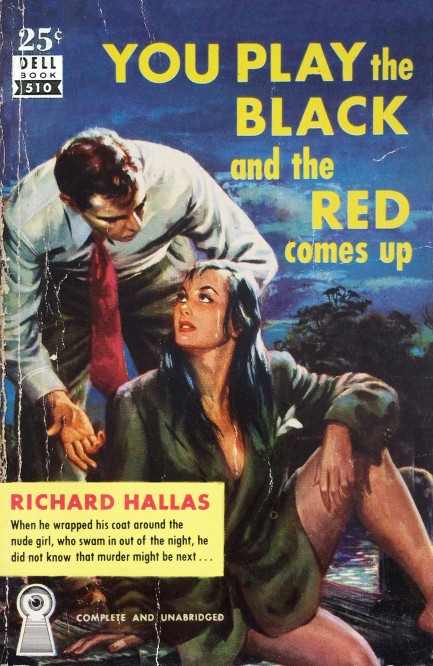

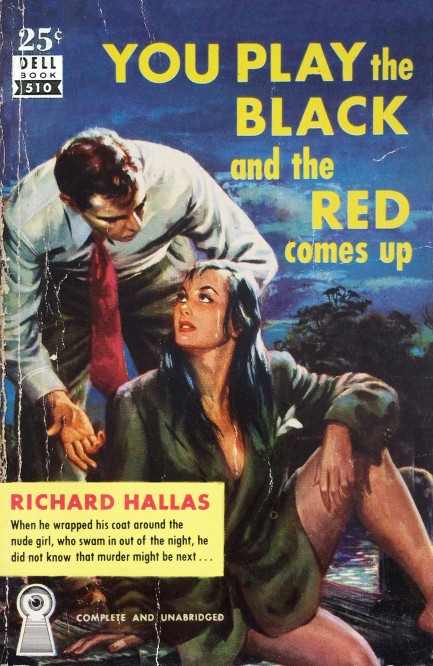

You're soaked. Good thing I was here to lend you my jacket. Now let's go somewhere and get you out of those wet clothes.

Bad luck. It's laid many a pulp protagonist low. In the 1938 thriller You Play the Black and Red Comes Up, written by Richard Hallas, aka Eric Knight, luck never seems to run the way the main character wants. The cover art on this 1951 Dell edition is by Victor Kalin, and depicts a scene in which the narrator Dick Dempsey gives his coat to a woman who has emerged naked from the sea. The fact that Dempsey is on the dock at that moment seems like the best possible luck, but luck can start good then turn bad, start bad then turn worse, and in all cases end up mockingly ironic. At one point Dempsey is trying his best to lose at roulette and the wheel hits black eleven times in a row, as he disbelievingly keeps letting his pile of cash ride. Then when he finally shifts it to red he's stunned when the wheel hits that color too.

The money that's causing Dempsey trouble isn't the fortune he won gambling—it's the fortune he stole during a robbery. In classic Damoclean style this loot hangs over him the entire book. He can't give it back, can't confess, and can't leave it behind. He just knows, like in roulette, whatever he does will turn out to be the wrong bet. You Play the Black and Red Comes Up is one of those books that was out of print for a while, but we can see why it was revived. Besides having the best title of possibly any crime novel ever written, its late-Depression, southern California setting makes a nice backdrop for weird events, bizarre characters, and outlandish existential musings. Critics of the day were divided on it. Was it homage to hard-boiled fiction, or a parody of it? To us it seems clearly the former. In either case, Hallas's tale has its flaws, but it's tough, spare, and very noir, all good qualities in vintage crime fiction.

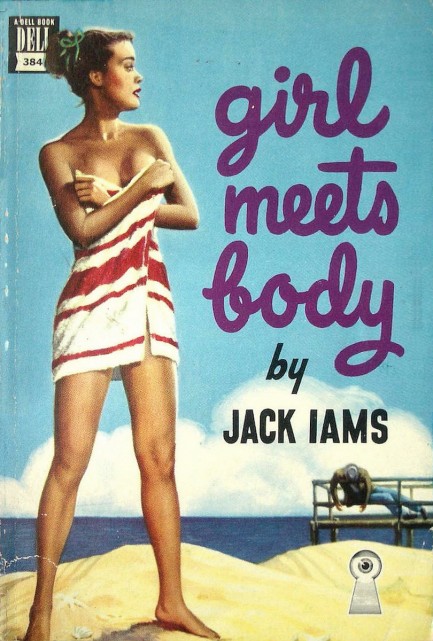

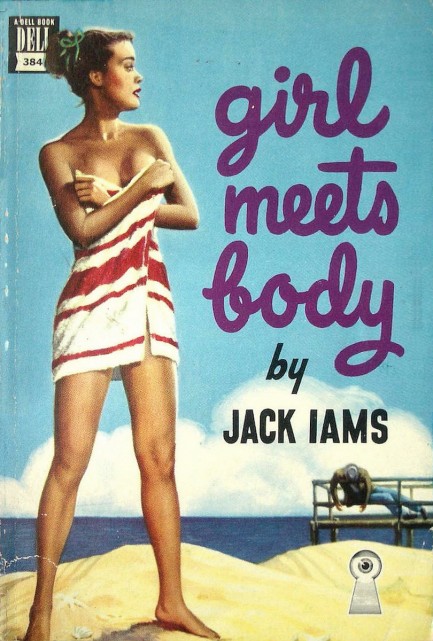

Wow, he sees me naked and drops dead. I guess all those guys were right—I do have a killer body.

Above you see a Victor Kalin cover for Girl Meets Body, written by Jack Iams for Dell Publications, and published in 1947. In the story a woman having a nude walkabout on a secluded New Jersey beach encounters a corpse. The discovery unleashes problems with police, mobsters, tabloids, and particularly her husband, who she married in England during World War II, before being kept away from him by the conflict for two years. The husband soon suspects this wife he barely knows and has spent only a few weeks with total has a secret connection to the murdered man. It sounds sinister, but Iams is not trying to be too serious with this book. Major characters are named Whittlebait, Barrelforth, and Squareless, if that gives you an indication of the feel. The writing style is a bit Thin Man, with numerous quips and asides, and the spouses, named Sybil and Tim, are cast as dueling lovebirds. Throughout the arguments there's never a doubt they'll work it out. They also work out the mystery, unconvincingly, but overall, we have to say the book was enjoyable. We were betting Sybil and Tim would be recurring characters, but it doesn't seem like that happened. Girl Meets Body is the first and last of them.

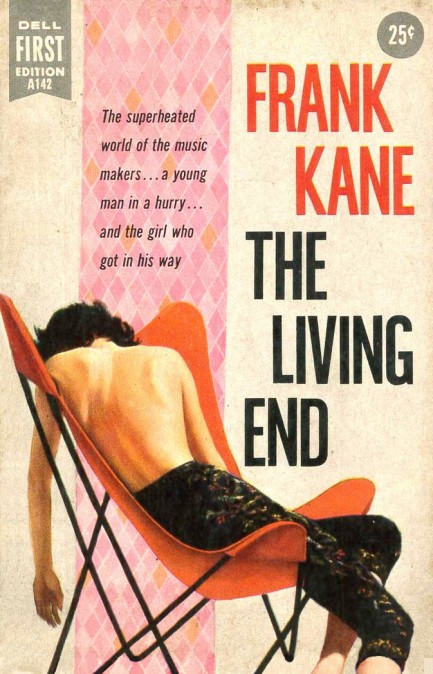

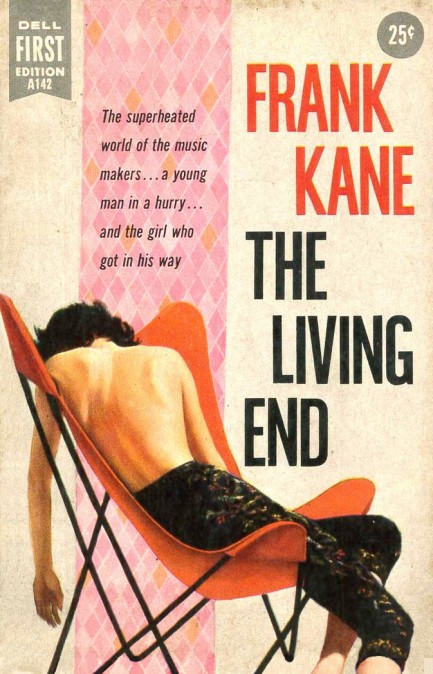

But it's important to make sure the pain is someone else's.

American author Frank Kane is well known for his many Johnny Lidell detective mysteries, which appeared from from 1947 to 1967. The Living End, from ’57, sets the world of detectives aside and tells readers about aspiring songwriter Eddie Marlon's meteoric rise from assistant at a radio station to the biggest disc jockey in New York City. Along with that, naturally, comes the usual doses of greed, betrayal, hubris, and the sowing of the seeds of his own potential destruction.

The cover art by Victor Kalin depicts the moment Marlon's ascent begins. A big shot record exec whips an ambitious singer until she's close to death, slumped shirtless in a chair. Marlon is called in to take the blame. It's a huge risk, because if she dies he's up the creek, but if she doesn't he'll be rewarded with anything he wants, which is his own radio show. The singer survives, keeps her terrible abuse a secret because she wants a career in music too, and Marlon gets an on-air slot and is soon rising through the ranks of FM radio deejays. The whole incident feels a bit Weinsteinian, which makes it all the more visceral. But did we mention those seeds of destruction? Getting to the top is hard, but staying on top is harder, particularly when you've stepped on so many people. The Living End is a good book, but one thing we didn't like was Kane's insistence on constantly—sometimes four or five times in a few pages—referring to Marlon as “the thin man.” Everyone within the narrative calls him “the kid.” So why not use that as his non-name reference? Strange. But otherwise, decent work, and a fun depiction of the payola days of FM radio. Apparently Kane revisited the music industry with a novel called Juke Box King. We'll try to find that and report back.

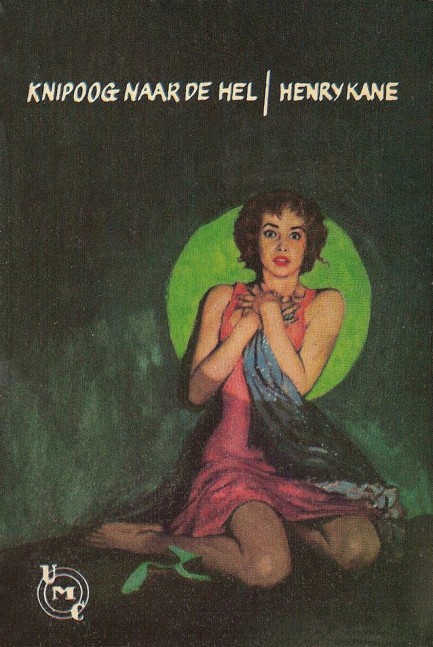

Caught you! Get back to the book cover you came from, young lady, and stay there!

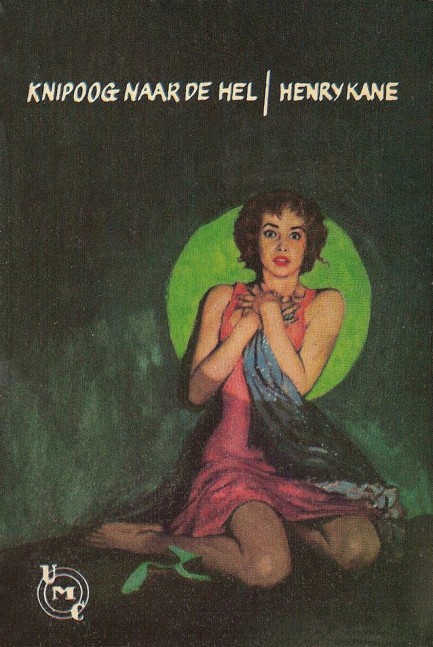

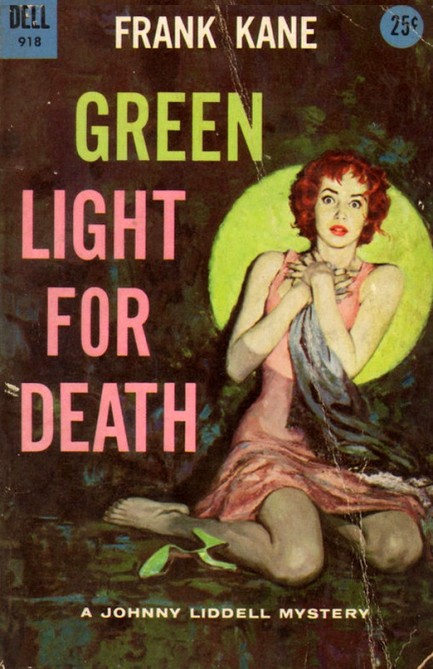

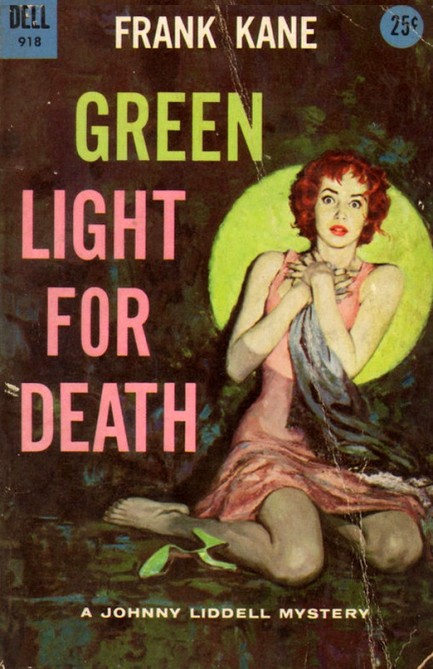

Above is a rather nice cover for Knipoog naar de hel, which in Dutch means “wink to hell.” This was published by the Rotterdam based company Uitgeversmij de Combinatie, and it's a translation of Henry Kane's 1964 thriller Snatch an Eye. As you can see at right (unless you're on a mobile device, in which case it's above), Uitgeversmij borrows art from Frank Kane's (no relation) 1956 Dell Publications novel Green Light for Death. The art for that was by Victor Kalin. The Dutch art is obviously a reworking of the original.  So here we go again. Is the copy by Kalin? Was it licensed? In this case, we think the art is Kalin's original, rather than a knock off by some random unknown, because the actual figure is identical, though the background has been replaced and the spotlight has a marginally different outline. Perhaps this was licensed and Kalin actually got paid, but we doubt it. Why bother to change it in that case? More likely it was appropriated via the use of a good camera, a crisp negative, and a little retouching. Whatever the case may be, we really like this piece. So here we go again. Is the copy by Kalin? Was it licensed? In this case, we think the art is Kalin's original, rather than a knock off by some random unknown, because the actual figure is identical, though the background has been replaced and the spotlight has a marginally different outline. Perhaps this was licensed and Kalin actually got paid, but we doubt it. Why bother to change it in that case? More likely it was appropriated via the use of a good camera, a crisp negative, and a little retouching. Whatever the case may be, we really like this piece.

*sigh* Maybe I should have left this outfit back home and packed a raincoat instead.

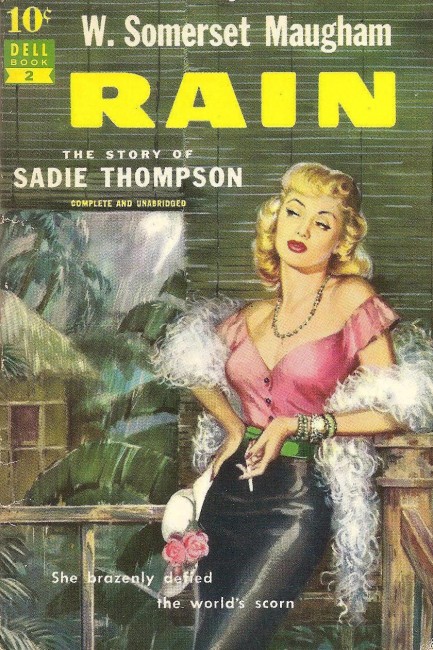

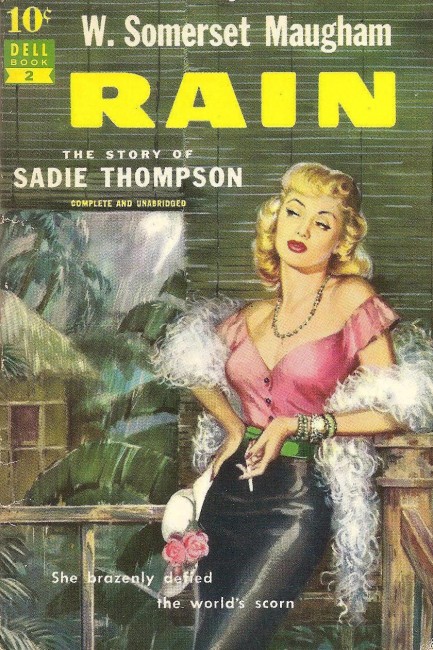

We talked about the 1953 Rita Hayworth film Miss Sadie Thompson back in December. The source material, written by W. Somerset Maugham, first appeared in the literary magazine The Smart Set in 1921 as “Miss Thompson,” and was published by Dell as Rain in 1951. This edition has beautiful cover art from Victor Kalin, belying the dark story Maugham weaves inside. The movie sticks reasonably close to the book, so if you want to know more about the plot you can check here.

|

|

The headlines that mattered yesteryear.

2003—Hope Dies

Film legend Bob Hope dies of pneumonia two months after celebrating his 100th birthday. 1945—Churchill Given the Sack

In spite of admiring Winston Churchill as a great wartime leader, Britons elect

Clement Attlee the nation's new prime minister in a sweeping victory for the Labour Party over the Conservatives. 1952—Evita Peron Dies

Eva Duarte de Peron, aka Evita, wife of the president of the Argentine Republic, dies from cancer at age 33. Evita had brought the working classes into a position of political power never witnessed before, but was hated by the nation's powerful military class. She is lain to rest in Milan, Italy in a secret grave under a nun's name, but is eventually returned to Argentina for reburial beside her husband in 1974. 1943—Mussolini Calls It Quits

Italian dictator Benito Mussolini steps down as head of the armed forces and the government. It soon becomes clear that Il Duce did not relinquish power voluntarily, but was forced to resign after former Fascist colleagues turned against him. He is later installed by Germany as leader of the Italian Social Republic in the north of the country, but is killed by partisans in 1945.

|

|

|

It's easy. We have an uploader that makes it a snap. Use it to submit your art, text, header, and subhead. Your post can be funny, serious, or anything in between, as long as it's vintage pulp. You'll get a byline and experience the fleeting pride of free authorship. We'll edit your post for typos, but the rest is up to you. Click here to give us your best shot.

|

|

So here we go again. Is the copy by Kalin? Was it licensed? In this case, we think the art is Kalin's original, rather than a knock off by some random unknown, because the actual figure is identical, though the background has been replaced and the spotlight has a marginally different outline. Perhaps this was licensed and Kalin actually got paid, but we doubt it. Why bother to change it in that case? More likely it was appropriated via the use of a good camera, a crisp negative, and a little retouching. Whatever the case may be, we really like this piece.

So here we go again. Is the copy by Kalin? Was it licensed? In this case, we think the art is Kalin's original, rather than a knock off by some random unknown, because the actual figure is identical, though the background has been replaced and the spotlight has a marginally different outline. Perhaps this was licensed and Kalin actually got paid, but we doubt it. Why bother to change it in that case? More likely it was appropriated via the use of a good camera, a crisp negative, and a little retouching. Whatever the case may be, we really like this piece.