If you can't count on on family, who can you count on?

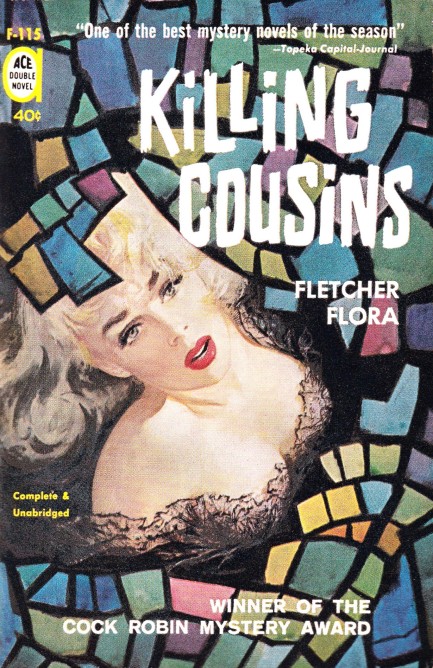

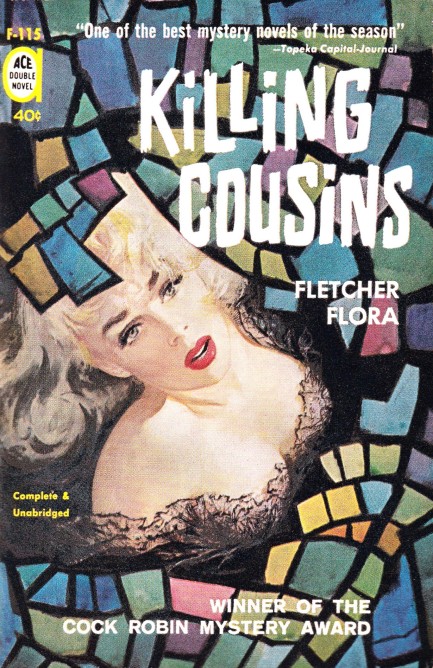

For a few years we've been meaning to get back to Fletcher Flora, and finally we've done it. Above you see his half of an Ace Double novel—Killing Cousins. The book is about a spoiled suburban wife who shoots her husband, then calls on one of her lovers—her husband's cousin—for help in covering up the crime. Cousin Quincy is known to be a genius, and he relishes the challenge of outwitting the cops. Generally, he does fine. It's the people around him he can't count on, including his cousin Fred, who, because he doesn't know about the murders and thus doesn't realize the importance of what he's asked to do, botches his crucial task. It's only the first of many problems.

Flora has a unique voice, no doubt about it. Some might find it too self-conscious, but we liked it. Check out the two examples below:

When she had first wakened and remembered what had happened, she had been very frightened and had felt a necessity to do something immediately, no matter what, but then it had occurred to her that it all might be nothing more than a bad dream, which she sometimes had, and so she had gone into Howard’s bedroom to make sure, one way or the other, and it had turned out not to be a dream at all, for there Howard was on the floor.

Heretofore, cousin Fred’s approach to women had been direct and simple, even somewhat primitive, and if the approach was no more than moderately effective on the whole, it had at least left him unfettered and uncluttered, free alike of uncomfortable commitments and emotional hangovers. If a chick would, she would. If a chick wouldn’t, she wouldn’t. And if she wouldn’t, to hell with her. That, in brief, was cousin Fred’s position.

Flora's writing feels like it comes from someone who knows exactly what he's trying for and absolutely achieves it. There are no missteps.

Plotwise, the murderous wife, apart from shooting her husband, is mostly a bystander. The success or failure of the cover-up rests entirely in cousin Quincy's hands, and he's confident to a fault. As holes develop in his clever plot, he's forced to improvise, and ultimately Flora boils the drama down to how fast Quincy can think, and whether the police are competent investigators. Speaking of which, we'll give Flora credit for one of the great cop names of all time—Elgin Necessary. We think Killing Cousins is a necessary read based on its unusual style alone.

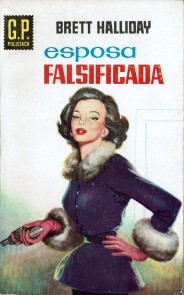

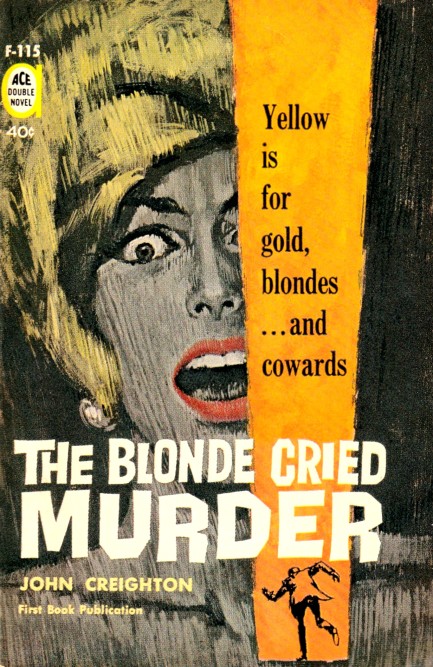

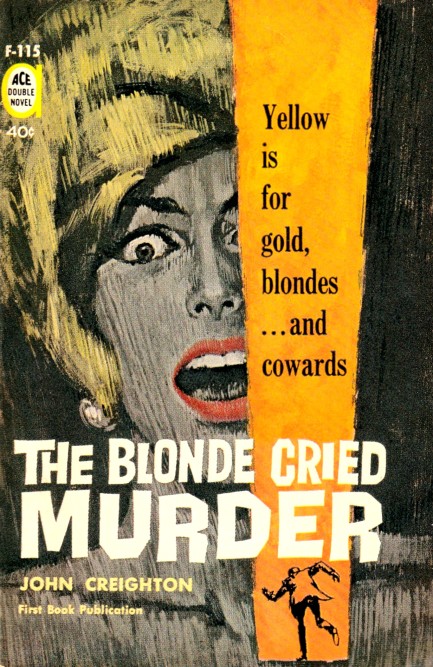

By comparison, John Crieghton's, aka Joseph L. Chadwick's, The Blonde Cried Murder is much more what you'd expect from a mid-century crime novel. The set-up sounds like the beginning of a joke: a woman walks into a detective's office. We like books that start that way. We think of such authors the way we think of musicians who decide to cover a classic. It's been done before, but not in that exact style. So, a woman walks into downtrodden private dick Ed Donovan's office and asks him to find a missing person—her husband, who may have fled to avoid the police.

of such authors the way we think of musicians who decide to cover a classic. It's been done before, but not in that exact style. So, a woman walks into downtrodden private dick Ed Donovan's office and asks him to find a missing person—her husband, who may have fled to avoid the police.

From there the tale continues in classic directions: Donovan drinks way too much, he's soon on the hook for a murder he didn't commit, there's money that needs to be found, etc. And of course, romance rears its inconvenient head. The book is an unusual flipside to Killing Cousins because of how standard it is by comparison, but it's worth a read. Not that you have a choice. To read one means to buy both. Some Ace doubles can cost a lot online, but this one is usually reasonable. There are two copyrights, 1960 for Flora and 1961 for Creighton, and the cover art for both is uncredited.

of such authors the way we think of musicians who decide to cover a classic. It's been done before, but not in that exact style. So, a woman walks into downtrodden private dick Ed Donovan's office and asks him to find a missing person—her husband, who may have fled to avoid the police.

of such authors the way we think of musicians who decide to cover a classic. It's been done before, but not in that exact style. So, a woman walks into downtrodden private dick Ed Donovan's office and asks him to find a missing person—her husband, who may have fled to avoid the police.