Aliens arrive on Earth to show humanity how killing is really done.

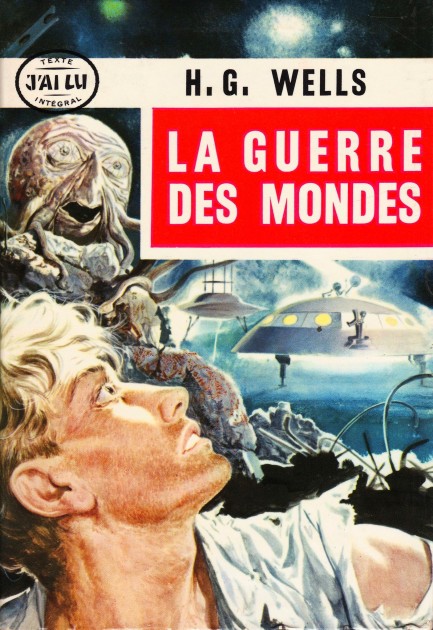

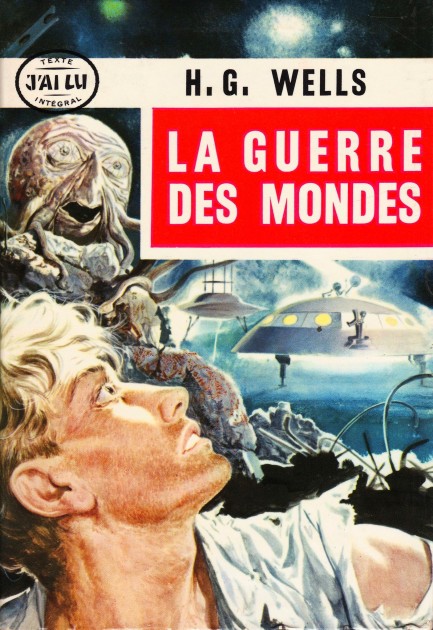

Above is a French edition of the 1898 sci-fi classic The War of the Worlds, published by Éditorial J'ai Lu in 1959 as La Guerre des mondes. H.G. Wells' vision of monstrous invaders with giant war machines, drooling mouths, and a thirst for human blood is still scary even today. The cover on this is by Italian artist Giovanni Benvenuti, a true master we've documented extensively. You can see what we've done on him by clicking here and scrolling down.

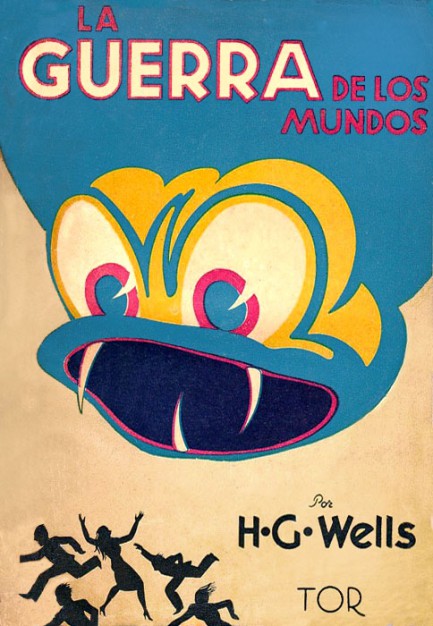

Argentine edition of classic takes art in different direction.

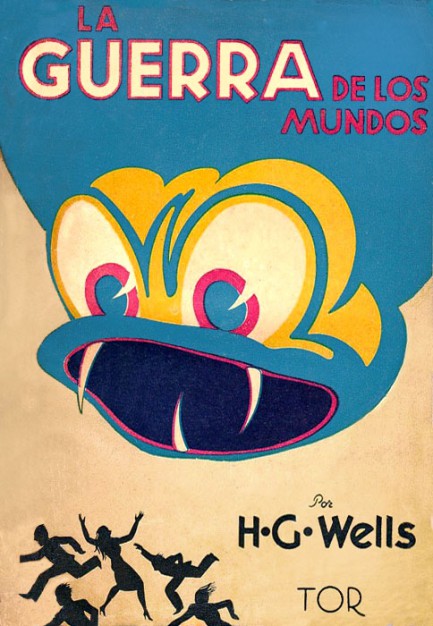

This 1938 printing of H.G. Wells’ 1898 masterpiece La guerra de los mundos, aka The War of the Worlds, leaps right to the top rank of covers we’ve seen. It was published by Buenos Aires based Editorial Tor, a company founded in 1916 by Juan Carlos Torrendell. Despite the demented Mickey Mouse aspect of the fanged alien, and the fact that it’s a completely different vision from any other cover treatment we’ve seen for the book, we think the overall feel of the piece is very much on target. Unfortunately we have no artist info.

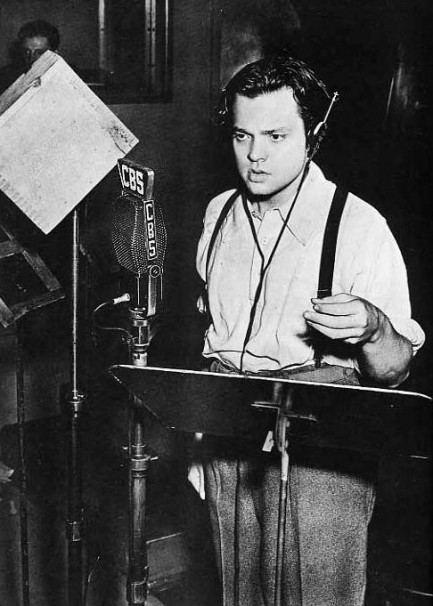

Blame it on the radio.

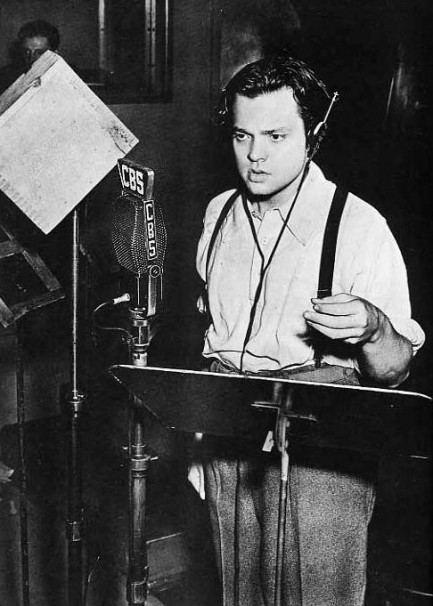

Today in 1938, Orson Welles vaulted into stardom by narrating his famous radio presentation of H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds. In adapting the novel, which concerns an invasion by malevolent Martians bent on the total destruction of humanity, Welles decided to use fictional news bulletins to describe the action. These were presented without commercial breaks, leaving listeners to decide whether the familiar sounding news flashes were truthful. Since a radio show had never used the news flash for dramatic purposes, many people were confused. The public reaction was described at the time as a panic, but historians now dispute that claim, suggesting that newspapers embellished the stories to make radio look bad. At the time print media feared radio would put them out of business, so they took advantage of an opportunity to deride radio broadcasters as irresponsible. Newspaper embellishments notwithstanding, there is no doubt the broadcast caused widespread anxiety. Only the first forty minutes of the show were in bulletin format—after that it would have been clear to listeners they were hearing a dramatization. But not everyone listened to the full hour. In the tense atmosphere that had been created by the lead-up to World War II, many people assumed they were listening to a broadcast about attacking Germans, rather than Martians. Some people left their homes, either to confirm events with neighbors, or to try and see the invaders for themselves. A crowd gathered in Grover’s Mills, New Jersey, where the attack was reported have begun. If there was indeed a panic, it subsided quickly when it became clear there were no invaders. In the end there was only one long-lasting effect from the broadcast—Orson Welles, who had been just another radio personality, became the most famous man in America.

|

|

The headlines that mattered yesteryear.

1939—Batman Debuts

In Detective Comics #27, DC Comics publishes its second major superhero, Batman, who becomes one of the most popular comic book characters of all time, and then a popular camp television series starring Adam West, and lastly a multi-million dollar movie franchise starring Michael Keaton, then George Clooney, and finally Christian Bale. 1953—Crick and Watson Publish DNA Results

British scientists James D Watson and Francis Crick publish an article detailing their discovery of the existence and structure of deoxyribonucleic acid, or DNA, in Nature magazine. Their findings answer one of the oldest and most fundamental questions of biology, that of how living things reproduce themselves. 1967—First Space Program Casualty Occurs

Soviet cosmonaut Vladimir Komarov dies in Soyuz 1 when, during re-entry into Earth's atmosphere after more than ten successful orbits, the capsule's main parachute fails to deploy properly, and the backup chute becomes entangled in the first. The capsule's descent is slowed, but it still hits the ground at about 90 mph, at which point it bursts into flames. Komarov is the first human to die during a space mission. 1986—Otto Preminger Dies

Austro–Hungarian film director Otto Preminger, who directed such eternal classics as Laura, Anatomy of a Murder, Carmen Jones, The Man with the Golden Arm, and Stalag 17, and for his efforts earned a star on Hollywood's Walk of Fame, dies in New York City, aged 80, from cancer and Alzheimer's disease. 1998—James Earl Ray Dies

The convicted assassin of American civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr., petty criminal James Earl Ray, dies in prison of hepatitis aged 70, protesting his innocence as he had for decades. Members of the King family who supported Ray's fight to clear his name believed the U.S. Government had been involved in Dr. King's killing, but with Ray's death such questions became moot.

|

|

|

It's easy. We have an uploader that makes it a snap. Use it to submit your art, text, header, and subhead. Your post can be funny, serious, or anything in between, as long as it's vintage pulp. You'll get a byline and experience the fleeting pride of free authorship. We'll edit your post for typos, but the rest is up to you. Click here to give us your best shot.

|

|