| Vintage Pulp | Apr 22 2020 |

If you put your fingers in the honey pot you're bound to make a mess.

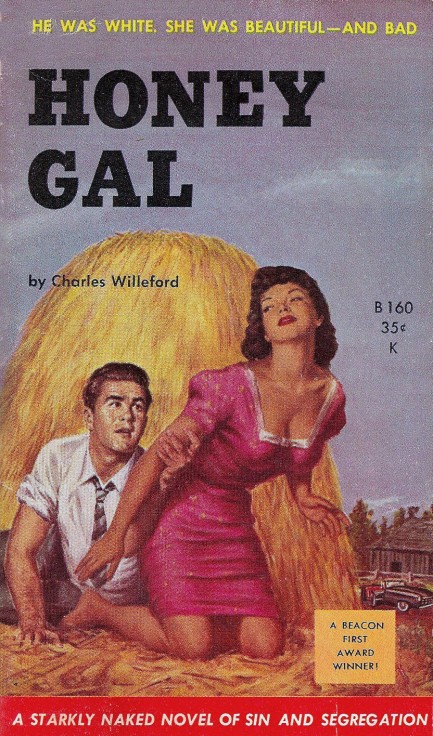

We recently read an essay giving Charles Willeford credit as the man who helped originate the genre of South Florida fiction, a profitable niche occupied by John D. MacDonald, Randy Wayne White, and many other authors. Willeford's 1958 novel Honey Gal, originally titled The Black Mass of Brother Springer, is the story of a writer who gets himself appointed minister of a black church in fictional Jax, Florida. He proceeds to use the position to pile up collection money with the aim of stealing it and running away to New York City with a beautiful local girl, the honey gal of the title.

This book is tricky. It's foremost a drama about a man who wants nothing more than a life of leisure, and realizes he's a natural born con man with the gifts to make his dream come true. But the tale is also improbable enough to come across as a farce, funny in parts, though too racially vicious to be considered a comedy, and satirical in the sense that it paints religion as generally a scam. It's a lot to digest, but even so the book, while interesting, is not what we'd call compelling. Willeford has daring ideas, but those who suggest he deserves consideration as a literary author overlook the fact that his writing is not executed at the highest level.

So we think of Honey Gal not as an overlooked classic, but as a somewhat unusual swindle novel written from the point of view of a religious charlatan. In his efforts to gain trust and accumulate cash, the main character accidentally finds himself in a position where his authority as a man of the cloth could do actual good. But will he let his plans for the sweet life be derailed by the opportunity to help others? Will he cool his ardor for that honey gal? Will he have an epiphany on the road to perdition? Hah. You know better than that. Willeford is an entertaining writer, no doubt. Honey Gal is about as different as genre fiction gets.

| Vintage Pulp | Aug 6 2019 |

Some guys just can't see the warning signs.

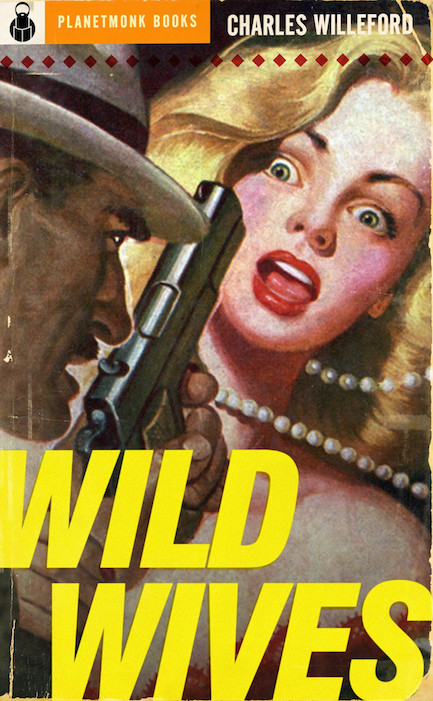

The cover art on this Planetmonk Books digital re-issue of Charles Willeford's 1956 novel Wild Wives enticed us with its faux-vintage look, plus the fact that this particular publisher has resurrected a few amazing old novels. This story was surprisingly one-note. You get a San Francisco gumshoe who crosses paths with an unhappily married femme fatale who's trouble with a capital T, and to that volatile mix is added a murder and 10,000 hidden bucks. The result is perfunctorily executed by Willeford. It's more frank than you'd expect, both in terms of violence and sex, and it's unusual for the hero's accepting attitude toward a gay character, but overall this isn't one of Willeford's, aka W. Franklin Sanders', top efforts. He's done well in the past, though, so we're confident about returning to him later.

| Vintage Pulp | Sep 3 2018 |

This is going to hurt you considerably more than it's going to hurt me.

Some years ago one of us bought a bullwhip. The opportunity was there to acquire a twelve foot version and be taught to use it by someone who made his living by wielding them at medieval fairs, so we leapt at the chance. As you may know, the crack comes from part of the whip breaking the sound barrier. It seemed like a cool idea to sew a piece of piano wire onto the end, which made the whip capable of gouging chunks out of trees. Generally, it only worked for five or six strikes before the wire tore loose from the tip, but it seemed like good, clean, twenty-something stupid-fun.

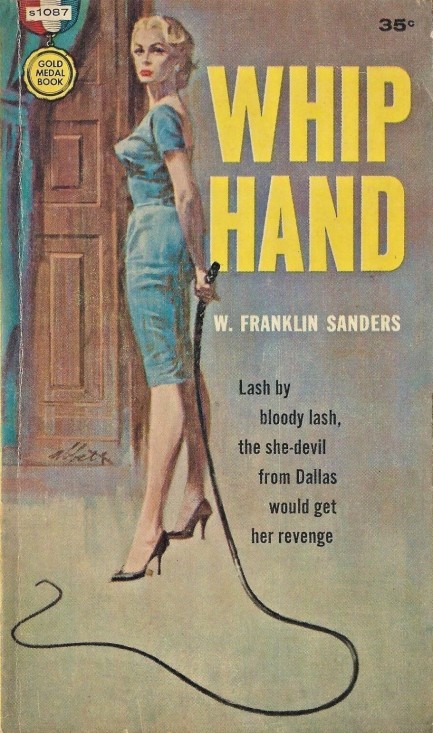

Whip Hand reminded us that bullwhips are no joking matter. Preferred instrument of torture for slave owners of the American south, they become central to the narrative of W. Franklin Sanders', aka Charles Willeford's Texas-based thriller when a character has his face flayed to pieces by an angry whip master. It's a brutal and bloody sequence in an uncompromising book constructed around a multi-p.o.v. first person narrative, each participant telling their own part, with not all of them managing to survive until the end.

The thrust of the story involves a kidnapping-turned-murder, a theft of the ransom money, and a chase to recover the stolen cash. The whip is never used by any of the female characters as suggested by the cover, but when it comes to paperbacks from the mid-century period you have to expect a bit of hyperbole. In this case the art is by the always brilliant Bob Abbett. Even without whip wielding femmes fatales, overall we liked Whip Hand. It's often barely realistic and isn't brilliantly written, but it's the type of tale that will get your attention and keep it. You can see some more whip themed paperback covers here.

The thrust of the story involves a kidnapping-turned-murder, a theft of the ransom money, and a chase to recover the stolen cash. The whip is never used by any of the female characters as suggested by the cover, but when it comes to paperbacks from the mid-century period you have to expect a bit of hyperbole. In this case the art is by the always brilliant Bob Abbett. Even without whip wielding femmes fatales, overall we liked Whip Hand. It's often barely realistic and isn't brilliantly written, but it's the type of tale that will get your attention and keep it. You can see some more whip themed paperback covers here.